A Highland Song is the next game from Heaven’s Vault and Overboard developer inkle. Lead designer Joseph Humfrey talks us through a hands-on demo.

Amid the bustle and clamour of London’s WASD indie games expo, I’ve found a rare moment of solitude. There may be gamers chattering excitedly and the oddly sickening smell of frying beef burgers in the air, but thanks to Joseph Humfrey and his Steam Deck, I’m far away in the Scottish Highlands.

I’m playing A Highland Song, the next game from inkle – the British studio that previously brought us such narrative-based delights as 80 Days, Heaven’s Vault and Overboard. A Highland Song sees inkle push itself into a subtly new direction, with less reliance on dialogue and more on traditional game mechanics; this latest project is a combination of 2D platformer, survival adventure, and most charmingly, rhythm-action.

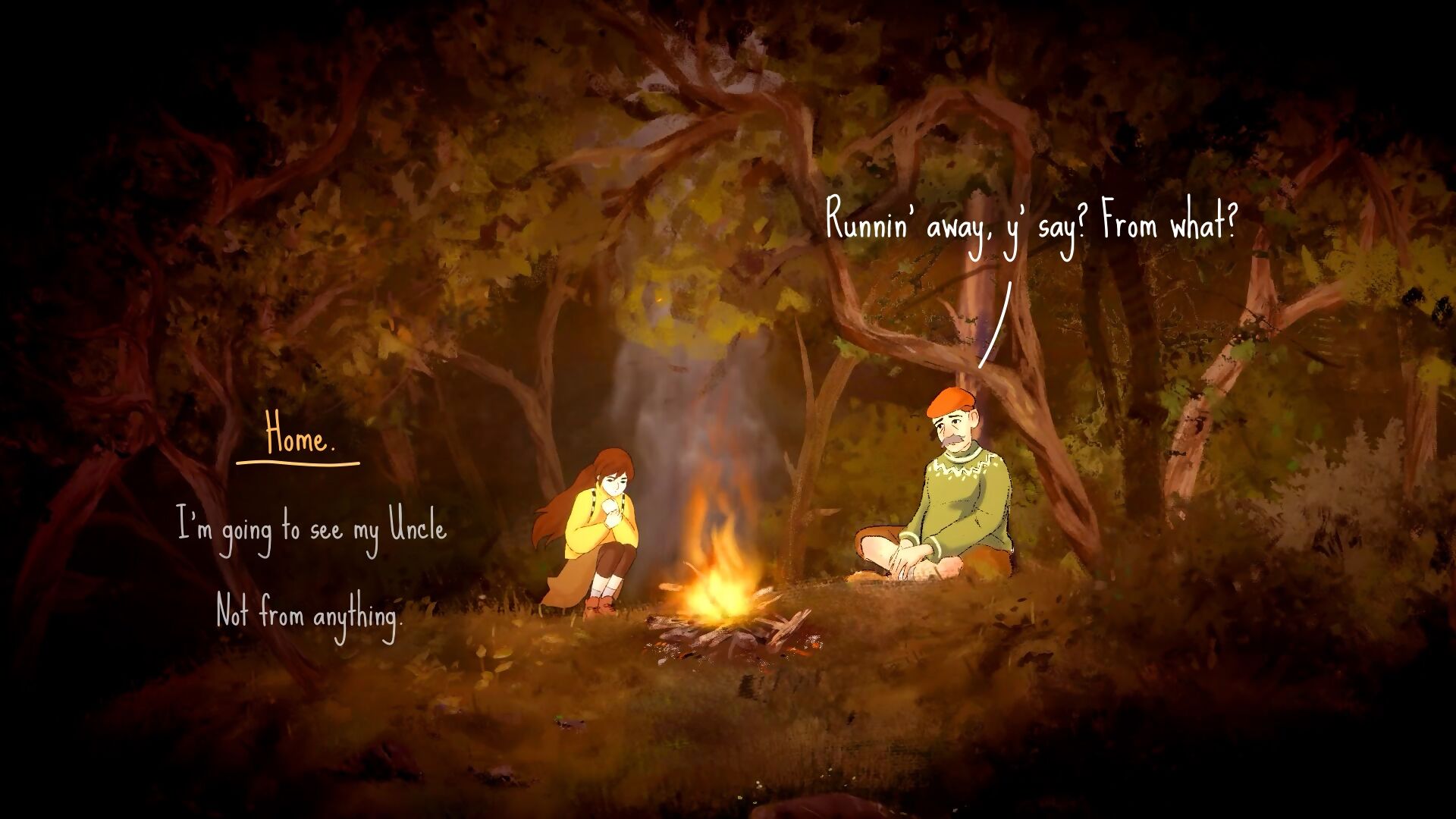

The player’s cast as teenage girl Moira, who somewhat rashly decides to set off across the Scottish mountains to her Uncle Hamish’s house, who lives several miles away on the coast. It’s a journey that takes in running and climbing, foraging for food, and finding shelter when night falls or black storm clouds begin to gather. But if all that sounds cold and harsh, my experience of A Highland Song is rather different; there’s an airy freedom to Moira’s adventure, underlined by some gorgeous hand-drawn animation and painterly, soft-focus backdrops.

“A lot of people use the word ‘cosy’ to describe it,” nods Humfrey, A Highland Song’s lead designer, when I describe its tone as ‘soothing.’ “It wasn’t what we were originally going for, but I think it’s a good thing.”

A Highland Song is rooted in Humfrey’s own youthful experiences. He was born in Dundee and spent much of his childhood growing up in Scotland. When a teacher took Humfrey and a bunch of classmates up into the Highlands for a bout of walking and camping, Humfrey was besotted. “I kind of fell in love with the landscape and the wilderness,” he recalls, before going on to point out something else about the region’s mountains: they may look beautiful, but they’re also dangerous.

“I actually got lost in the Highlands with some friends,” he says. “It was quite a scary experience, actually. Unlike the Lake District, which is quite tame – if you go down the side of a mountain you’ll always find a town at the bottom – large areas of the Highlands are genuinely empty. It can be extremely dangerous if you get lost there.”

By this point, I’m still wandering around A Highland Song’s virtual mountains as Moira, but now wondering what on earth happened to the young Humfrey up there in the Highlands. How lost did he get, exactly?

“It started to get dark,” Humfrey recalls. “We’d gone down into the wrong valley and then we got even more lost. I had a friend who’s more silly than I was – he’d just watched the first Lord of the Rings film, which I think had just come out. There were scenes of Aragorn running over the mountains, so he felt inspired by that. He said, ‘I’ll just run to the top of this peak, try to figure out where we are, and come down again.’”

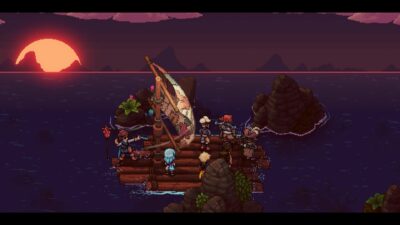

Credit: inkle

Unfortunately, Humfrey’s friend failed to figure out much of particular use. “If anything,” Humfrey says, it just got us more lost because by then we’d split up. He was off in one place and the rest of us were somewhere else.”

“Then it got dark,” he adds.

Fortunately, salvation came in an unlikely form. A deer stalker turned up, ushered the youths into the back of his Land Rover, and drove them several miles to a mountain located next to a car park. Along the way, the stalker pointed to a nearby beauty spot. “See that waterfall?” he said. “A teenager died there a few years ago.”

Understandably, the whole experience left a lasting impression on Humfrey – so much so that, when he was sitting on his sofa at home one day, playing on his Switch, he began to think about making a game that was about exploring the Highlands. And exploration is a big part of A Highland Song; despite the 2D perspective, it’s far from a linear experience.

Pointing to the mountains in the game’s hazy distance, Humfrey explains that all the background elements are locations the player will eventually get to explore. During my time with the game, I could bring up a sketch map of the mountains and compare its landmarks – an unusually-shaped rock or a lighthouse, say – with those on the landscape around me. By lining up the two, I was able to uncover paths that led me into the screen to the next mountain range.

Credit: inkle.

Says Humfrey, “In a way, I like to think of it as a traditional dungeon crawler, in that you have this 2D space you can explore, and then you find a trapdoor to take you into the next layer of the dungeon. Except it’s laid out on the Z axis, moving into the screen, basically, so you’re going forwards through the world to reach the sea as you venture across the Highlands.”

What’s striking is how seamlessly all of A Highland Song’s genre elements slide into one another. One minute I’m climbing craggy rock faces, the next I’m galloping down a hill, jumping in time to the upbeat music by composer Laurence Chapman. “At its heart, it’s a narrative adventure,” says Humfrey as Moira hops and skips to the music, “but we’ve included light elements of platforming, rhythm, survival, strategy. None of them are super hardcore. The rhythm part is to give a sense of exhilaration and flow. It’s to represent the flow state you get into when you’re going on a long walk.”

Whether she’s climbing, jumping, or huddling down to keep warm by an NPC’s campfire, Moira’s movements are exquisitely drawn by lead animator Flora Caulton; Humfrey initially assumed that hand-drawn animation would be beyond the indie developer’s scope, thinking it’d take an entire team of artists to render each frame. Incredibly, Caulton has drawn each of Moira’s “thousands” of frames by herself, with an in-house artist at inkle adding colour afterwards.

“I love seeing [Caulton’s] process,” Humfrey says, “seeing her start from a sketch. It’s incredible to see, and gives it a slight Studio Ghibli feel, which I love.”

Credit: inkle.

Jordan Mechner’s original Prince of Persia was another influence, not just in the fluidity of A Highland Song’s animation, but also in the hint of realism in Moira’s abilities. “It’s the groundedness,” Humfrey says. “You’re not jumping ten times the height of a house.”

That groundedness really comes into play in the game’s survival moments, when storm clouds gather and you have to find a place to shelter, and also in the game’s sparse but disarmingly natural dialogue. During one stumble, Moira says to herself, “Christ on a velociraptor!” It’s one example of how narrative director Jon Ingold manages to convey a lot of character in just a handful of words.

After several years in various stages of development (“two years full-time and two or three years of simple prototypes and stuff”), A Highland Song is now on its home stretch. The remaining work, Humfrey says, involves things like bug fixes and placing hand-painted textures on the mountainous levels designed by Natalie Clayton. As he says this, a deer wanders past Moira. “We want to add more animals,” Humfrey says. “More birds and stuff.”

As the demo ends and the screen fades to back, I feel a pang of disappointment as I’m teleported out of inkle’s soothing Highlands and back to the burger smells and chatter of the expo. Again, the game may be partly inspired by a quite scary childhood experience, but its sense of wistful nostalgia is what truly shines through. Far from a one-to-one recreation of a real location, A Highland Song evokes the sensation of being young, energetic and fearless.

“In a way, this is me going back to Scotland,” says Humfrey, who now lives in the much flatter environs of Leicestershire. “Because if I can’t go there, I can at least make a game about going there.”

A Highland Song is coming soon to PC via Steam and Nintendo Switch.