Two years before Capcom changed the fighting genre with Street Fighter II, a British team made a sequel of its own. We talk to Leigh Christian, the artist behind Human Killing Machine.

It’s difficult to overstate just what a pivotal moment Street Fighter II was for gaming. Released in 1991, it breathed new life into a flagging arcade scene, and became the new benchmark for fighting games. Launching a generation of imitators, Street Fighter II gave Capcom a bankable series that is still going strong over 30 years later – the much-anticipated Street Fighter 6 is mere days away from launch at the time of writing.

Street Fighter II’s success was so all-encompassing, however, that it almost entirely overshadowed its predecessor. Released in 1987, the original Street Fighter had plenty of elements that would find greater fame in the sequel: there were the conspicuously large characters and variety of moves (including Ryu and his Dragon Punch), and the globe-trotting locations, including England, Japan and Thailand. The game even had a six-button layout – a system Capcom hastily came up with when it emerged that Street Fighter’s initial, pressure-sensitive controls were leaving boisterous players with injured fists.

Street Fighter was popular enough that several companies licenced the game and ported it to home systems. In Japan and the USA, the PC Engine CD version was developed by Alfa System and released as Fighting Street. In the west, the home computer ports were handled by a Macclesfield-based studio called Tiertex, and were published in 1988 by US Gold.

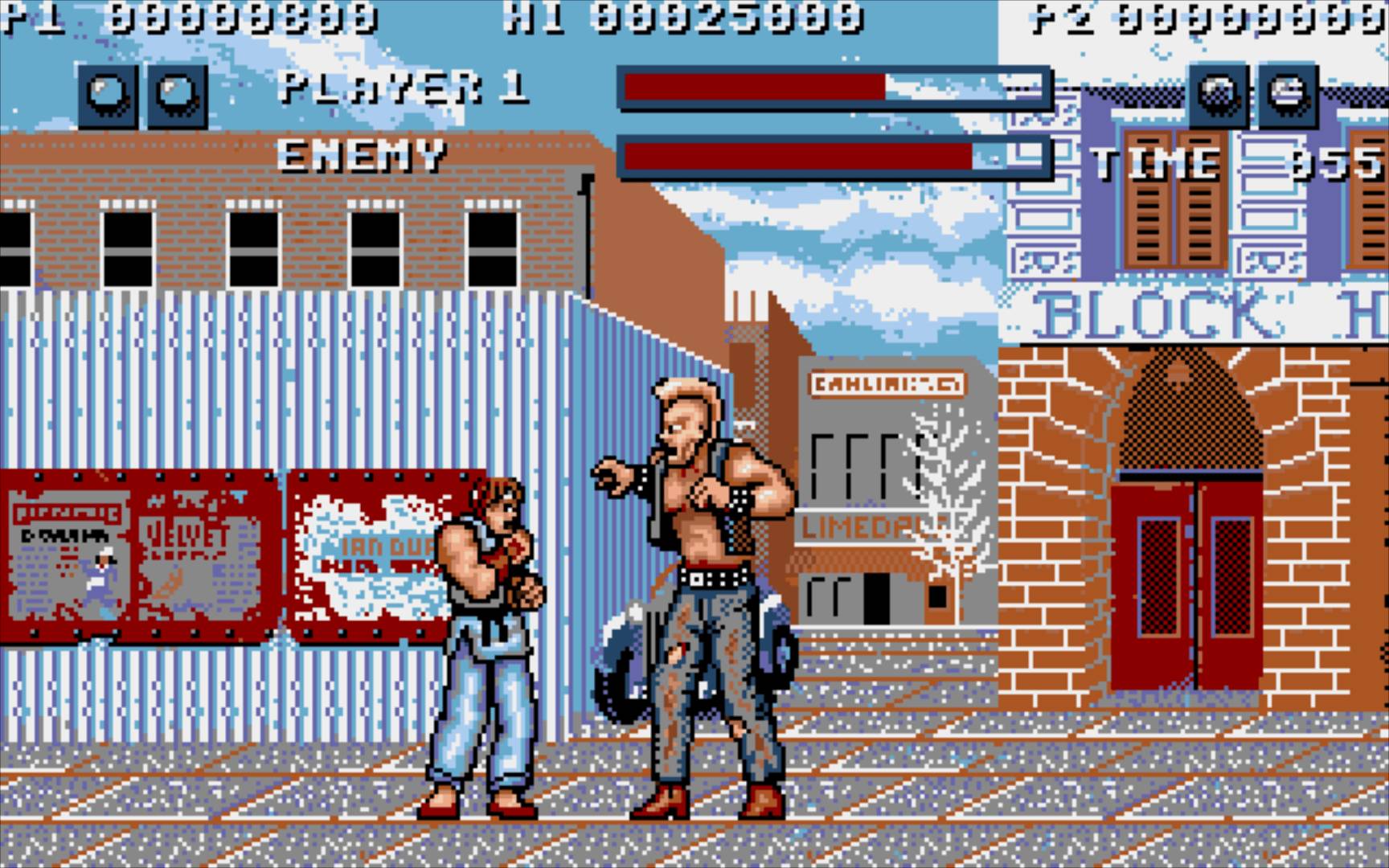

Street Fighter on the Amiga, as ported by Tiertex.

Street Fighter’s home versions were somewhat limited, not only in terms of graphics and sound, but also controls; computers like the Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum and Amiga supported single-button joysticks, which reduced the number of moves available and made pulling off said moves considerably fiddlier. Nevertheless, Street Fighter must have sold relatively well – because publisher US Gold quickly commissioned a sequel (of sorts).

Initially called Human Killing Machine – Street Fighter II, the sequel was first mentioned in a round-up of US Gold’s upcoming games in an October 1988 edition of Crash magazine. A representative at the publisher, Dave Baxter, said that the game would “Knock your head off and slash your throat” – an early hint at the finished product’s ‘edgier’ tone.

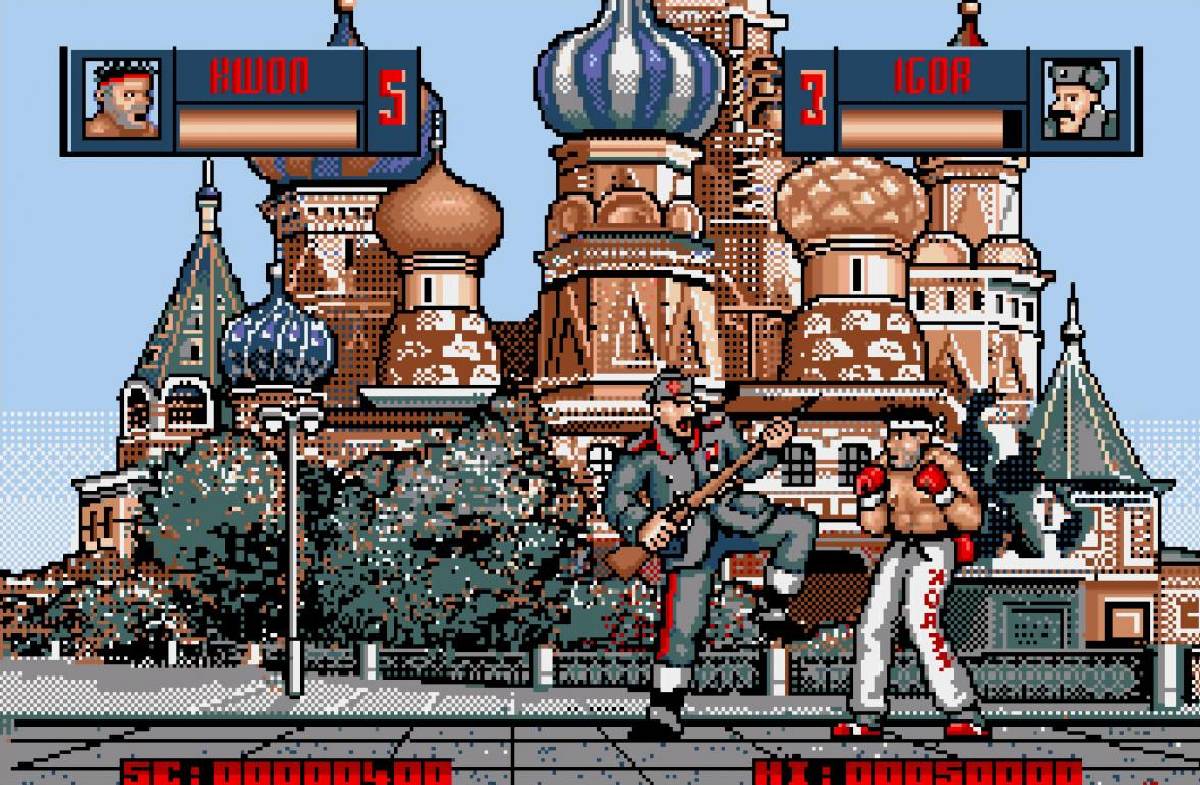

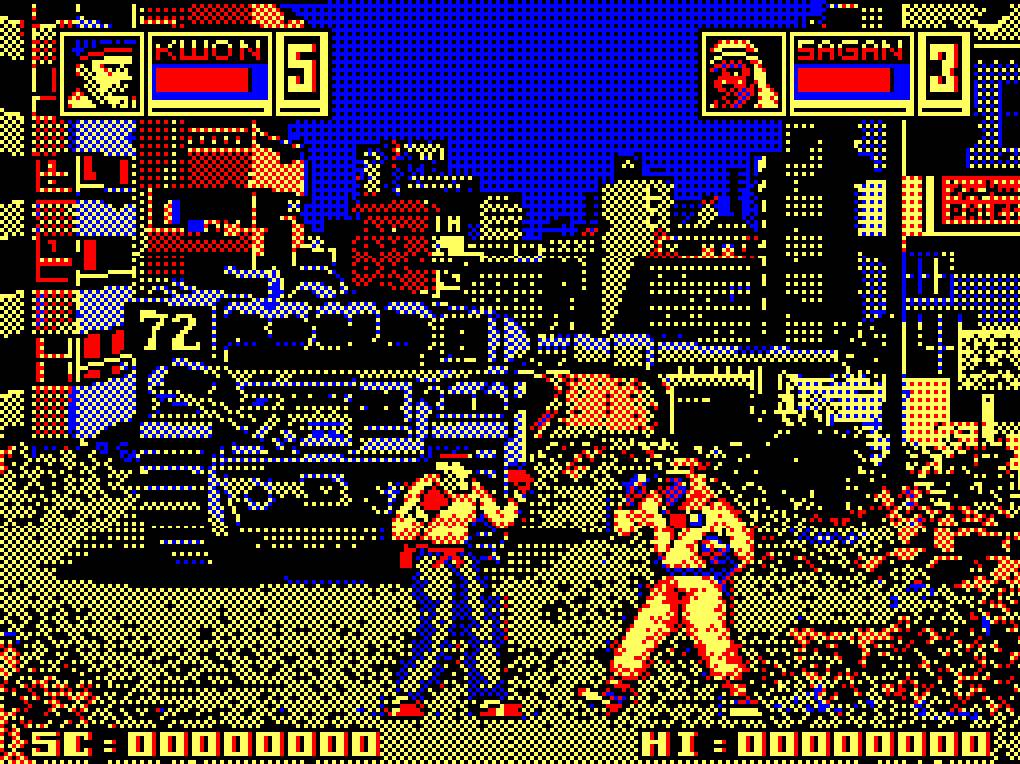

Human Killing Machine’s colour palette varied between platforms. Here’s the MS Dos version, which was among the more colourful.

Human Killing Machine was again developed by Tiertex, with Mark Haigh-Hutchinson handling the design and programming. Haigh-Hutchinson had an illustrious career in video games both before and after Human Killing Machine; he went on to work on the likes of Zombies Ate My Neighbours, Shadows of the Empire and the Metroid Prime trilogy before he died in 2008 at the tragically young age of 43.

For Human Killing Machine’s graphics, Tiertex again turned to a company called Blue Turtle, a tiny firm founded by Nick Pavis and Leigh Christian – two teenagers who were still at school in the late 1980s. Blue Turtle got its start when the pair wrote a game for the Amstrad CPC. “We sent it off to some companies and Tiertex replied,” Christian tells us. “They liked the graphics and asked if we could convert arcade games to home computer formats.”

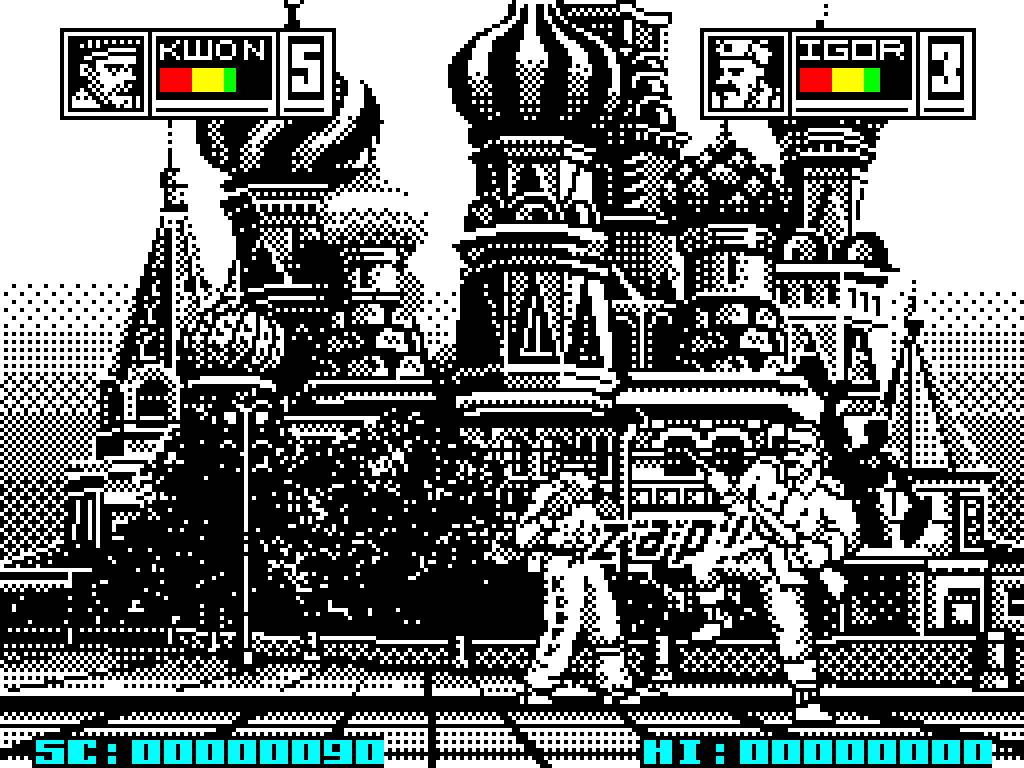

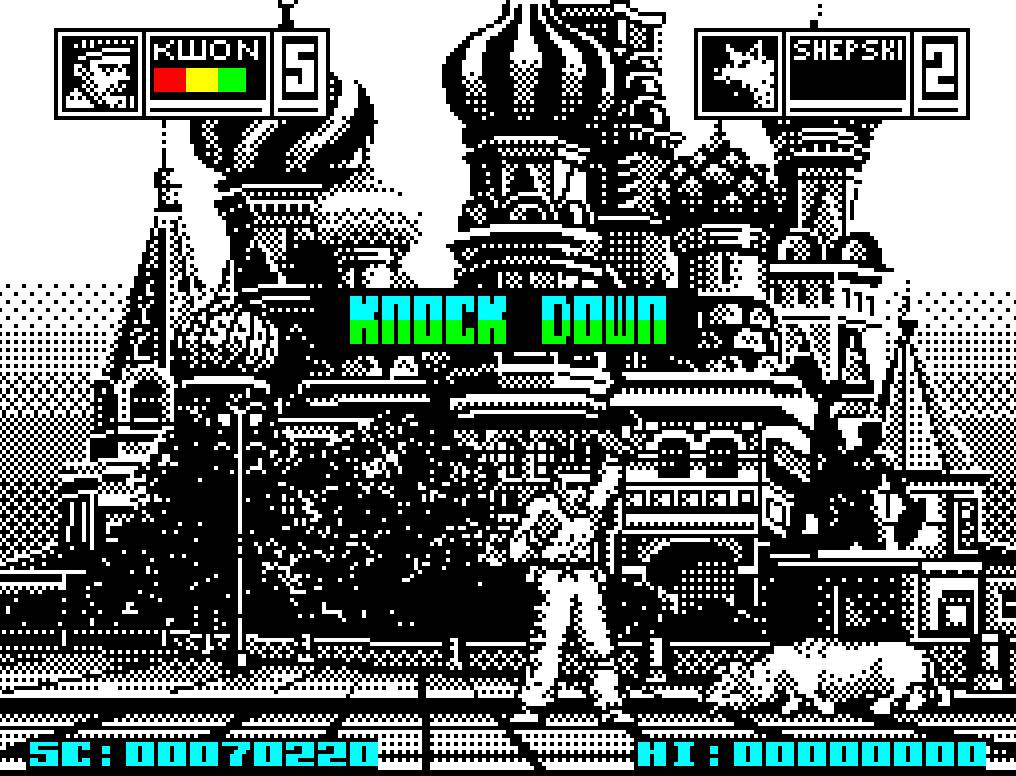

Despite the limited colour palette, Christian’s St. Basil’s still looks nicely detailed.

Blue Turtle’s first job for Tiertex (and publisher US Gold) was Rolling Thunder – a home computer port of Namco’s pioneering run-and-gun coin-op. It was one of many projects that Blue Turtle undertook for Tiertex and US Gold in the late 80s, with other titles including ports of Sega’s Thunder Blade, Capcom’s Last Duel and, of course, Street Fighter. Pavis and Christian were just 15 years old at the time.

Work on Human Killing Machine got underway in late 1988 – while Pavis and Christian were off school – and by Christian’s reckoning, the entire game was finished “in less than six weeks.”

“I was just a teenager making graphics in my mate’s bedroom, listening to Lou Reed and eating Marmite on toast,” Christian says.

The final stages take place in Beirut, where the player fights a pair of terrorists. This is the Amstrad CPC version.

Like its predecessor, Human Killing Machine’s fights took place against a variety of global backdrops, most strikingly St Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow. Given the limitations of the computers the game ran on, those backdrops were surprisingly detailed and true-to-life. “St Basil’s was my proudest moment,” says Christian. “All hand-drawn on an Amstrad without the use of a mouse or Wacom [tablet] as they weren’t available in 1987.”

Human Killing Machine’s combatants were a varied bunch, and also somewhat politically incorrect by modern standards. Players had just one character they could play as – Korean martial artist, Kwon – and as in Street Fighter, the goal was to travel to various locations, beating up people and – in HKM’s case – the occasional animal. In the Soviet Union, the opponents were a burly soldier, Igor, and his canine sidekick, Shepski. The opponents in Spain were a matador named Miguel and a bull called Brutus. Germany? A bottle-throwing waiter named Hans.

Ignore the title – as well as humans, the game also saw you beat up a dog and a bull.

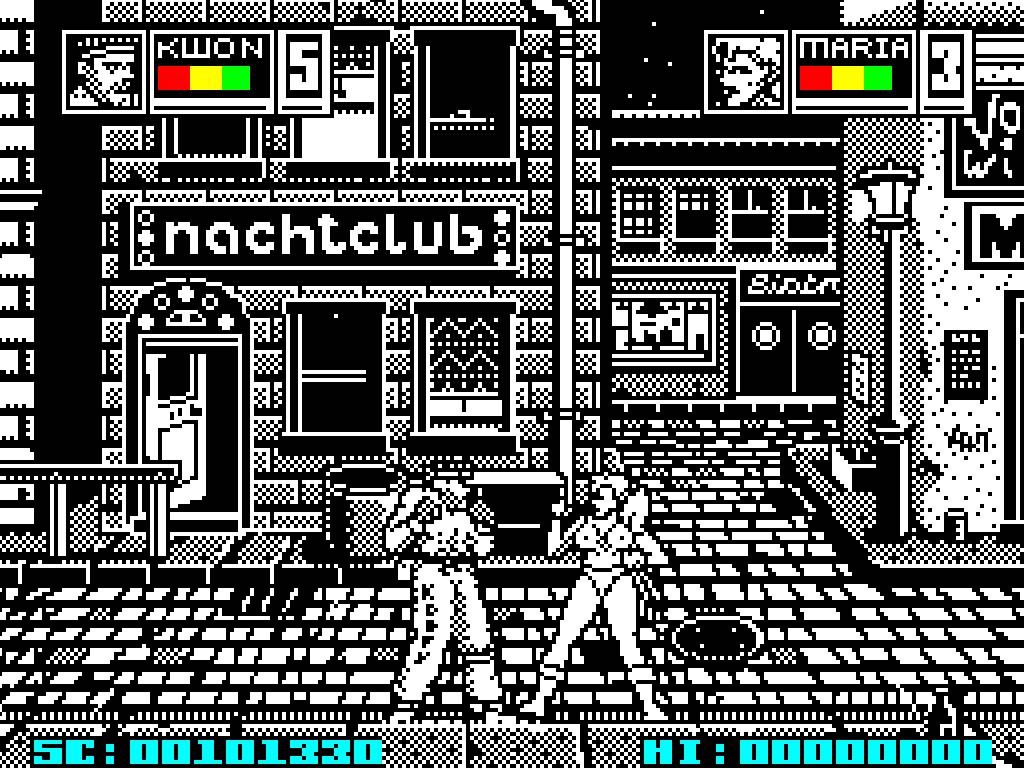

Racial and national stereotypes have long been a contentious part of the Street Fighter series – see such staples as Dhalsim and T. Hawk to name but two – and Human Killing Machine certainly followed in this unfortunate tradition. The most questionable examples were, perhaps, Maria and Helga, a pair of sex workers the player fought in Amsterdam’s red light district. Then there was Sagan and Merkeva – a pair of terrorists located in Beirut.

“I think they [Tiertex] just let two naive teenagers loose without any real consideration for the outcome,” says Christian now. “It’s strange, looking back, that nobody mentioned anything in all the national reviews about the edgy approach. I guess games were in the Wild West stage and the audience was very niche, mainly teenage boys.”

Human Killing Machine was released – minus the Street Fighter II subtitle – in March 1989, and verdicts varied wildly; Sinclair User scored the game 78 percent, for example, though other outlets, such as ACE Magazine, were more critical (“It’s not original stuff and is probably one for the real beat-’em-up hardcore”).

To modern eyes, Human Killing Machine’s faults are more glaring; the backgrounds may be detailed and the characters impressively large, but this comes at a cost – the animation is “shockingly poor,” as Christian admits.

Kwon takes on one of two ‘Ladies of the night’ in Amsterdam’s red light district.

Nor did Tiertex manage to come up with a better control system than the one in its Street Fighter port; once again, moves were restricted to a handful of punches and kicks. In fact, the moveset was almost identical to Street Fighter’s, which merely serves to underline that both it and Human Killing Machine are broadly the same game under the bonnet (“Tiertex wanted to cash in, obviously,” says Christian. “I’m not even sure where the name came from.”)

The true Street Fighter II came out two years later, conquered the world, and instantly made every other fighting game – including the original Street Fighter – look like the product of a wobbly, bygone era. All the same, Human Killing Machine remains a fascinating footnote, and it’s fun to think that a comparatively small British company – and a pair of teenagers drawing graphics in their bedrooms – managed to beat Capcom to the punch by almost two years.

Leigh Christian still works as an art director in the games industry today, and most recently collaborated with his old Blue Turtle partner, Nick Pavis, on the mobile game League of War: Mercenaries. Almost 35 years on, Christian evidently looks back on Human Killing Machine with affection.

“There’s a hilarious video review of HKM on YouTube that highlights the massive racial stereotypes in an entertaining way,” he says. “None of it was intended to offend, and judging from many of the comments, I think international players saw the humorous side. Apologies to any large ladies called Helga living in Amsterdam. Please forgive my teenage self.”