For better or worse, 2021 was the year non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, entered the video gaming mainstream. Multiple studios began to embrace blockchain technology, many of them assuring gamers that non-fungible tokens would revolutionise the medium. With gamers spending increasing amounts of their lives in online worlds, the opportunity to share ‘ownership’ of those spaces might, the thinking goes, seem appealing.

In reality, however, a sizeable subset of gamers – perhaps wearied by years of loot boxes and pay-to-win business models – have reacted with suspicion and even hostility to NFTs. While the response in the indie sector has been somewhat different, the triple-A gaming space has witnessed a furious revolt from players, in part because early implementations of the technology have more than a whiff of microtransactions 2.0 about them.

Atari has already combined its technology with loot boxes to promote its 50th anniversary. Ubisoft became the subject of much ire and ridicule following the news that its Ghost Recon Breakpoint NFT promotion appeared to have amassed only a few hundred dollars in resales. Although Ubisoft pointed out that its Breakpoint NFTs weren’t designed to make the company money, it’s clear that the promotion was intended to gauge interest in a wider NFT launch across some of the publisher’s more profitable titles.

Defenders argue that blockchain gaming could potentially offer value to gamers – not least by allowing, in theory, ownership and resale rights over digital games – but so far, publishers have largely focused on cosmetic items and loot boxes. This has, in turn, bred a certain amount of distrust among players, many of whom reject the technology outright. “Gamers are always sceptical about new ways for publishers to monetise,” says Stephanie Llamas of VoxPop, an industry analyst in the sector. “Monetisation has sometimes been perceived as almost predatory in the past, and gamers are notoriously wary of this.”

TRUE DIGITAL OWNERSHIP?

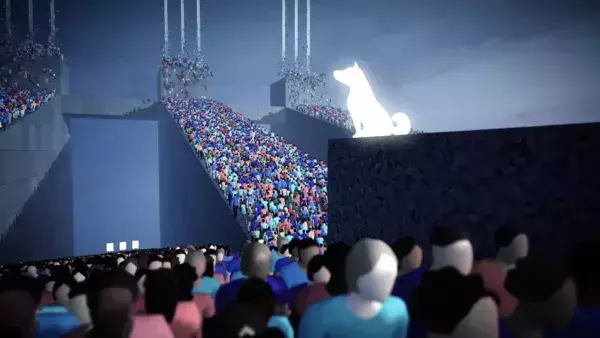

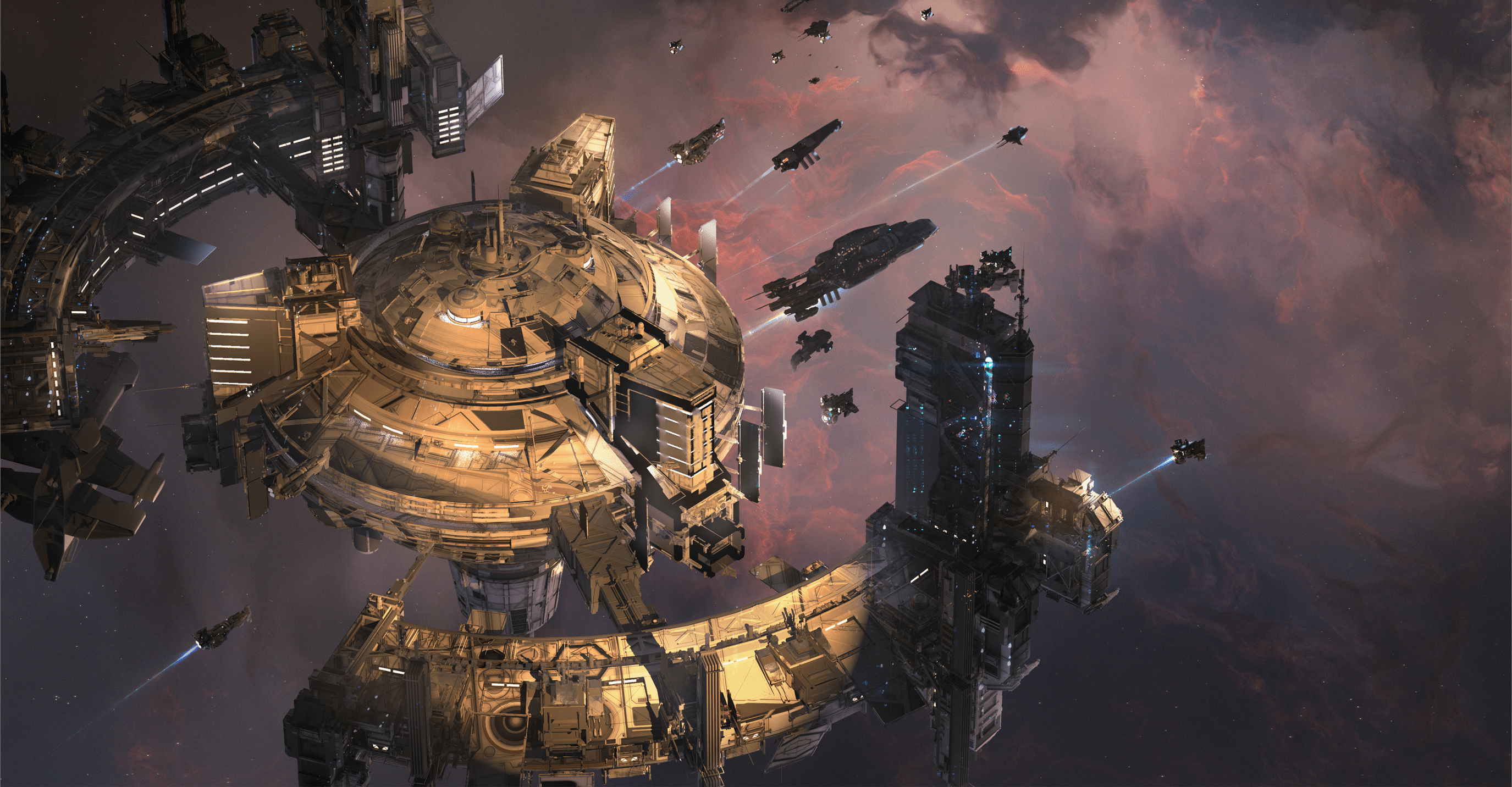

Cutting through the perceived negativity won’t be easy, but several studios are making the attempt. Blowfish Studios’ upcoming action RPG, Phantom Galaxies, promises to offer space battles in starfighters that transform into giant mechs. Players will own their generative avatars and upgradeable mechs as NFTs, meaning they retain control over them. As the game develops, this will allow players to add value to their in-game assets through playtime and upgrade systems. If they so choose, they’ll be able to place their NFTs on a digital marketplace to sell, netting them cryptocurrency profit for the time they’ve spent playing the game.

You could learn to play Mozart’s Requiem in D minor quicker than winning a cosmetic NFT in Ubisoft’s Ghost Recon.

Where publishers like Ubisoft and Atari have pounced on the speculative aspects of the NFT market, Blowfish is eyeing a longer-term vision. “I’m not here to make you money,” asserts Ben Lee, the studio’s co-founder and managing director. “I’m here to make you a great game, to get you to play the game. If it challenges traditional asset ownership, if you’re participating and you’re making money out of that, then that’s great. But what we’re here for is to make games that are fun, that people will play no matter what kind of monetisation is there.”

One challenge Blowfish has faced so far is Valve’s decision to block all NFT-based games from Steam, which has meant that Phantom Galaxies will have to find its audience without the help of the gaming’s largest digital storefront. “Steam [was] kind of saying we don’t want your blockchain game on here,” says Lee. “We had to go and build our own distribution, so you can get the game off our web page.”

Despite the scepticism from some quarters, though, Tony Hauber – developer of the cheekily titled Nifty Villages, an upcoming resource and crafting-based NFT title – believes the technology itself isn’t inherently problematic. “I always think of crypto and NFTs as a hammer,” he says. “You can use a hammer to build something, or you can use it to bash in somebody’s skull. Does that make the hammer evil? No, it just gives the wielder power to do evil or good things with it.”

‘Evil’ might sound like a strong word, but reports of so-called ‘play to earn’ models, such as Axie Infinity, where grinding the game can accrue real-world value to NFTs, are cause for concern. Research and consulting firm Naavik published a report in 2021 concluding that Axie Infinity’s in-game economy (where players pay an upfront cost amounting to hundreds of dollars for NFT ‘Axie’ avatars, before adding value within the game to them), was ‘unsustainable’.

If Axie Infinity’s economy was entirely in-game, nerfed by developers to promote grind, or push players towards microtransactions, that would be one thing. Because Axie’s economy has real-world implications, its high entry fee and unsustainable growth model have led many commentators to liken it to a pyramid scheme. According to Naavik, with its current trajectory, the game’s economy will eventually crash, and with some communities in the Philippines said to rely on the income they make from the game, that’s a sobering thought.

Nifty Villages will eventually feature all kinds of terrain, including lava.

It’s easy to see why some publishers are willing to structure NFT economies in such a way. If gamers are willing to pay $600 to access your product, that’s a big profit upgrade on the $70 price that triple-A games sell for. Lee concedes that while it’s bound to happen, titles like Phantom Galaxies can have just as much sway in influencing the narrative surrounding NFT games. “The blockchain is an open system, anybody can create what they want,” he says. “There are people taking advantage of the current market; it’s a capitalist society and we can’t do anything about that. All we can do is keep speaking [about] what we’re trying to do, and build our community around that.”

“I got sucked into the mania too,” says Hauber of some of his original design choices for Nifty Villages. “I thought we’d have these finite numbers of plots as NFTs, they could blow up and become really valuable, but then I realised if the assets that I build become really valuable through player speculation, then I damage the game. If it costs hundreds of dollars to start playing, like in Axie Infinity, then I’m stopping people from playing the game because the speculation around it has bumped up the prices to the point where it’s impossible for people to afford to play it.”

Axie Infinity’s use of NFTs has also given rise to scholarship programs, another phenomenon that has the potential to be economically exploitative. Because of the prohibitive buy-in price to acquire Axie NFTs, certain companies offer to front this cash, before then taking up to 50 percent of the player’s future profits. The system allows less affluent gamers to enter the play, but it’s also an ultra-refined digital-capitalist model, straight out of the dystopian future of Ready Player One. In short, it polarises wealth. And while stories of gamers in the Philippines using play-to-earn as a means of combating poverty has made headlines, Llamas suggests that’s just another example of the crypto market’s penchant for self-promotion: “I believe the case study for the Philippines is a small sample that has been hyped up to make play-to-earn out to be the cash cow that it just isn’t,” she says. “Play-to-earn is not nearly as popular as many people think. Entry into NFTs takes a lot of research, and it’s a consolidated market. Many gamers just want to turn on their PC, phone, or console and jump in.”

By contrast, Hauber is developing Nifty Villages in response to his awareness of the models used by games like Axie Infinity. “I don’t want people to be playing the game to earn a minimum-wage living,” he says. “I think that would be a horrific use of the tool that I’ve devised to be used for fun. I don’t want my game to be about speculation. Speculation drives that aspect [of play-to-earn] where people believe in developing an asset purely because it has some speculative value.”

Phantom Galaxies has all the trappings of an epic action RPG, like these thumpingly big ships.

Having previously designed games for Facebook’s platform, Hauber understands the kind of game economics that encourage mini-maxing, grinding, and the temptation to circumvent such processes through microtransactions. Add real currency into the mix, and he’s aware of the lengths gamers might go to in order to boost the value of their NFTs. As such, he’s being careful to design the game to ensure that the pure enjoyment of ‘play’, whether that be mining, crafting, or just exploring, is preserved: “I don’t want people to spend their entire lives on this,” he says, explaining how he intends to ensure that his game can’t be turned into a crypto-farming tool. “You have a daily energy, and you spend that energy, and once that’s gone, you’re done mutating the state of the world for the day. That doesn’t mean you have to stop playing, because everybody else is spending their energy to mutate the world, so you can walk around the world and see stuff.”

It’s a potential solution to a fundamental issue that all NFT-based games will have to face, no matter how enjoyable or sophisticated their systems may be. If players can use them to build monetary value, player exploitation of those systems is inevitable. “Everything you do, if you’re giving players the opportunity to add value, then that can be exploited,” says Hauber. “It’s about designing your game so players would literally have to break the game to use it that way. I’d be devastated if that was the case.”

It’s a principle that Lee agrees with. Having played blockchain games since their emergence a year or two ago, he notes the uneven nature of those early titles. “Some crashed, some were scams,” he remembers. “Devs came in, took the money, and ran. Playing these games enabled us to see what did and didn’t work, including from an integrity point of view. Being a traditional games developer and just loving making games, the challenge was being able to bring traditional gaming and blockchain gaming together, and have people enjoy them.”

RULING THE WORLD

Beyond allowing players to own their game assets, Lee also wants to give the player a modicum of control over the game world itself. “The key pillars to me? True digital ownership is one,” he says. “I firmly believe in that, along with governance. I’ve always wanted to make a game where players can have player-driven governance, and we can do that with NFTs and crypto.”

Earning governance tokens in Phantom Galaxies will gradually confer control of the game from developer to players, with the aim that eventually, Phantom Galaxies “will evolve into a community-owned, decentralised autonomous organisation”.

Hauber wants Nifty Villages to chart a similar path, and plans to relinquish control over the game by promoting local economies, while also allowing players to figure out what to do when the game’s finite resources run out. “I’m excited to build a game,” he says, “where nobody has the control to shut off the value that players have earned from that system.”

“One day all of this will be villages…” – a shot from an early build of Nifty Villages.

It’s a fascinating experiment in social, economic, and gaming terms. While there are those who argue that decentralisation has a causal link to inequality, games like Phantom Galaxies and Nifty Villages are spaces to explore and challenge those notions. Both titles run the risk of forgoing certain revenue streams by surrendering control over the game world, but both developers say they’re looking at ways to continue to turn a profit if that happens. “We’re trying to figure out a way to monetise Phantom Galaxies,” says Lee. “After all, it’s still a commercial business. We want to keep the studio going and stay profitable to make bigger and better games, but in a way that we hope will be sustainable. There’s no guarantees, but that’s the goal.”

Hauber isn’t certain that profitability is guaranteed in Nifty Villages, either, but he’s sanguine about the game’s earning potential: “If the economy works,” he says, “money will come back to me somehow. I don’t need to be rich off this. The more my desires are about getting rich from Nifty Villages, the more value I’m destroying from the integrity of what the game could be.”

NFTs form part of what’s been dubbed Web3, a decentralised internet that will reputedly put power back in the hands of gamers. But, as we’ve seen from several major publishers, the tech could be used as another means to part us from our cash. Hauber isn’t too worried about the profits-first approach that has characterised much of the first wave of NFT usage. “When fans come out and say, ‘Ubisoft, we don’t want you making NFTs’, that doesn’t deter me at all. I’m glad. If Web3 is really supposed to be like Web1 again, then it has to be for the little guys first. Scepticism is healthy for the development of technology that will help people, which is the goal.”

Lee also thinks the only way to change players’ minds about NFTs is by using the tech to create unique experiences. “We can complain about NFTs and the bad side of it, or we can try to be the title that proves everybody wrong, and achieves what people think you’ll never do. I like to challenge these things from the inside out.”

Addressing player concerns will be key to changing the perception surrounding NFTs, according to Llamas. “I don’t necessarily believe games will completely back off NFTs,” she argues, “but there needs to be real incentive for them to buy into NFTs. Do other people actually want to buy NFTs from players? What’s their value outside the game? I think those are some of the questions Ubisoft has struggled to answer.

“In the meantime, before publishers like Ubisoft or Square Enix can be successful, there needs to be education, and I think Ubisoft in particular knows that.”

Until that moment arrives, perhaps judging each project by its own merits and maintaining a healthy scepticism remains the wisest course of action. “I don’t mind somebody looking over my shoulder to see if I’m doing something evil,” jokes Hauber, “because I don’t want to do something evil, and that will help me make sure I don’t.”