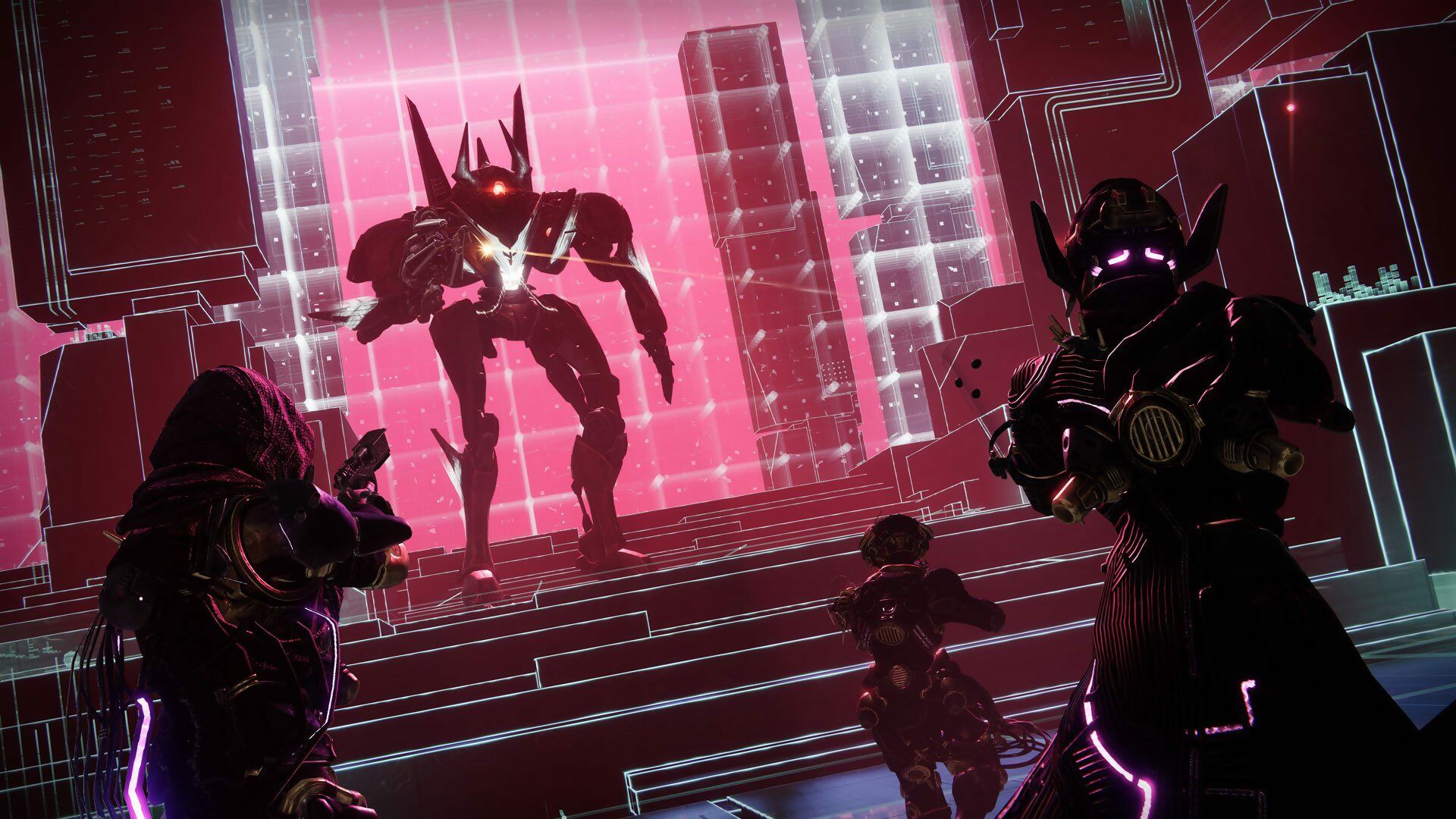

Playing Destiny 2 during this summer’s Season of the Splicer, the game’s latest seasonal content drop, I was pleasantly surprised by the portrayal of the player’s character as the ultimate weapon of a dominant, if waning, empire.

The latest storyline features beloved main characters on the side of the player, decrying xenophobia against refugees and apologising for their genocidal attacks against the Fallen, an alien race on the verge of extinction. It’s a good example of a game understanding the characters’ place in the universe, and their relationships with others who find themselves in a position of material desolation.

Examining Destiny as a critique of imperialist and colonial practices, however, I found that very few games share this nuanced understanding of the power a certain few wield against those they see as subordinates. Then, I arrived at the conclusion that in their desire to give freedom of choice to the player, western open-world games such as Destiny can often lead to players replicating those relationships of control. This happens once the game hands the sandbox’s keys to player bases who are taught about history from the perspective of a western colonial power. Simply put, players will imitate the world around them once they’re in the driver’s seat.

For example, despite its progressive plot line, the game repeatedly asks players to kill the very same Fallen that the narrative apologises for slaughtering – all to gain access to new weapons, upgrades, and materials, or simply to progress other story quests.

Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory game director and writer Clint Hocking calls this disconnect between what the player does in control of a game’s character and the description of the game’s linear story “ludonarrative dissonance”, and Destiny 2 is not its only sufferer.

The Far Cry series encourages players to dominate their environment through gameplay design and narrative language, regularly asking them to “liberate” enemy camps and harvest exotic flora and fauna. Subsequent entries in the series have shifted some of the more egregious displays of exploitation to the villains, but since the gameplay loop is vastly the same between entries, the resulting narrative is strikingly familiar – the western man with the right tools for the job ventures into uncharted territories and justifies through economics, religion, or political ideology their exertion of control over land and those who inhabit it.

It’s no secret that a lot of world powers throughout history have been propelled by their colonial extraction of seemingly unlimited natural resources found in other parts of the world. These notions of expansion and extraction are the by-product of capitalist practices where there is a relationship of control and subordination.

A lot of the criticism levelled at games for upholding outdated colonial values could simply be dismissed with a very chilled “Dude, these are just games”. Games are a welcome escape from a world in which we are often beholden to the whims of private markets, and our choices often feel limited. They offer a playground where our decisions have a tangible impact on our environment and we are free to express ourselves within the context of the game world. Should they also need to make politically coherent statements about imperialism and colonial practices to be taken seriously? Perhaps not.

But if the industry seeks to gain more recognition for its storytelling capabilities and unique interactivity, then it would surely be in the interests of game developers to create with a more critical mindset, placing in the spotlight artists, writers, and designers who understand the extraction and exploitation of natural resources in their homeland, or those who have seen at first hand the impact that electoral meddling – caused by world powers with their own economic interests – can have on working-class people.