Game developers are increasingly looking to Brutalist architecture when creating their virtual worlds. Here’s why…

“For me, it evokes a kind of coldness,” NaissanceE’s creator Mavros Sedeño says of Brutalist architecture. “Something artificial, unfriendly and non-human. Like if we were just units that could be put in boxes, arranged in the optimal way for maximum efficiency, with no thought for our wellbeing.”

If you live in a city, you’ll likely be acquainted with Brutalism: the hulking, spare concrete buildings that sprang up in the postwar era of the 1950s to the seventies. Even today, the style elicits strong reactions of fascination or perhaps even outright hatred – which makes Brutalism a great choice for games, because architecture is so useful for creating specific emotions in players.

Concrete levels aren’t new to games; they’ve appeared in nineties titles like Quake, GoldenEye and Medal of Honor. Those simple grey textures were often borne out of necessity, but nevertheless created memorable atmospheres by combining austere corridors with claustrophobic bunkers. Brutalist structures have also appeared in more recent, big-budget titles, from the futuristic worlds of Halo and Deus Ex to the cold, alt-histories of Dishonored, Wolfenstein: The New Order and Control.

More recently, we’ve seen developers use Brutalism in more deliberate ways. As they tap into ideas of authority and control, we’re beginning to see more conscious explorations of concrete architecture, and a deeper engagement with Brutalism’s history.

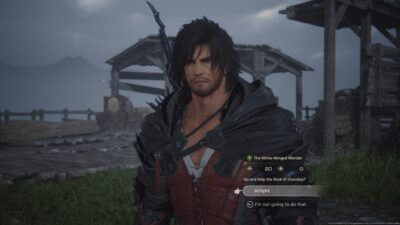

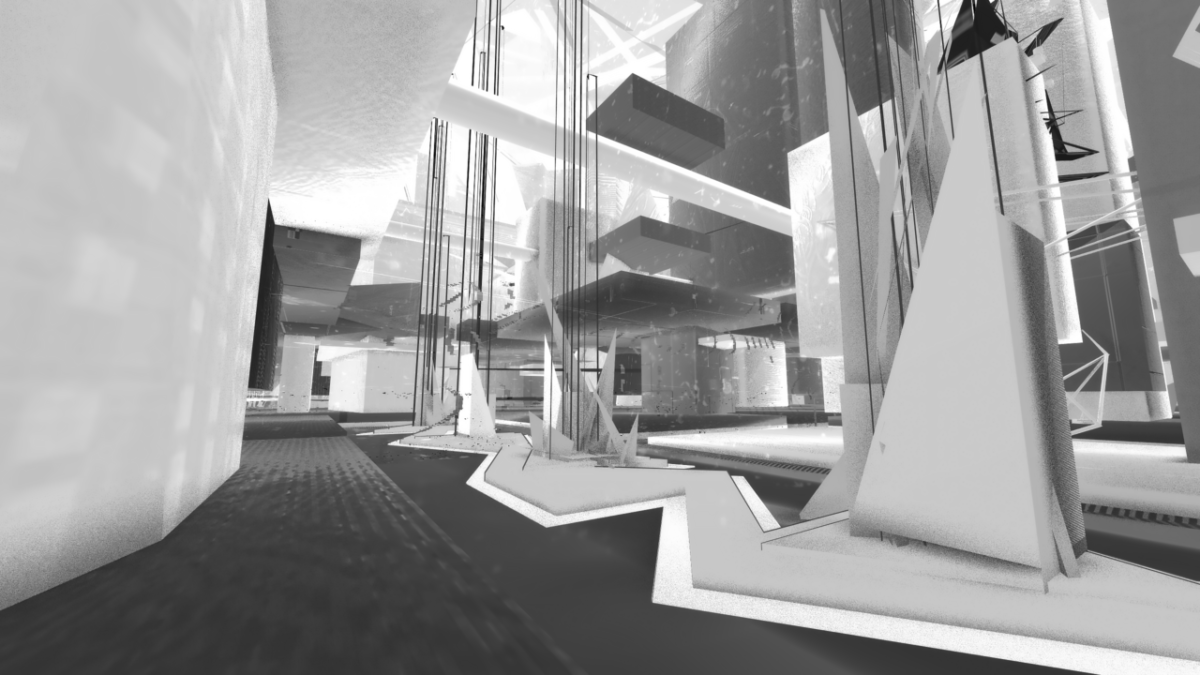

Not only do we get a feel for the colossal scale in NaissanceE, but also the strange, gravity-bending effects of a structure without universal referents like the sky or a horizon.

Concrete accident

There’s still nothing quite like 2014’s architectural exploration game NaissanceE. An obscurity turned cult classic, the game sees you scrambling through the monochrome halls of an endlessly shifting megastructure. NaissanceE and Brutalism seem perfect for each other, and yet — as so often is the case in game development – the connection was accidental. NaissanceE designer Mavros Sedeño tells us that he “wasn’t aware of Brutalism until late in development” – it was only later that he discovered that some of the artists he was inspired by were connected, often loosely, to Brutalism. What fed into his work was as much the things he saw in “movies, comics and video games”, as the stuff he learned in art school or through wandering the streets of Paris.

“I can say for sure I had the work of Frank Lloyd Wright in mind when I made NaissanceE,” Sedeño tells us. A massively influential modernist, you can spot manifestations of Wright’s early 20th century style in Brutalism’s concrete forms — if you’ve seen the sci-fi classic Blade Runner, you’ll have seen some of his Los Angeles buildings in there, too.

Sedeño lived in Marseille for a time, and so the work of Le Corbusier, in many ways the father of raw concrete, may have also seeped into his psyche. Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation (Housing Unit) along with other “big blocky concrete buildings” and “low-income housing”, as Sedeño describes them, can be found in the poorest parts of Marseille; they are, he adds, “the dystopian realisation of utopian visions.” What began as a social project embodying progressive ideals — to have buildings meet every social need – deteriorated over time. It’s common to see Brutalism as a short-hand for overbearing governments and sometimes even outright totalitarianism.

For Sedeño, NaissanceE’s architecture induces “the same emotions” as real-world Brutalist architecture. “It’s all enveloped by this insecure, anxious aura,” he says. “The feeling of being small, swallowed up and digested by the architecture, the city and those big, repetitive shapes.”

These atmospheric elements come through clearly in NaissanceE, but they also stem from the real experience of urban life, where we’re surrounded by an ever-growing multitude of large, often concrete, buildings. We become strangers in an inhospitable land. The city is a powerful source of anxiety, “a place where you don’t belong and feel weak and lost.” It’s these emotions that Sedeño attempts to communicate — blown up to vast proportions in NaissanceE.

Brutalist architecture formed the backdrop for Remedy Entertainment’s Control. Credit: Remedy Entertainment

Aesthetic power

Indie developer Moshe Linke is the first to admit the artistic debt he owes to NaissanceE. A few years ago he even created a fan sequel, with Sedeño’s blessing, called VoyageE. While NaissanceE may have shown Linke what was possible in the virtual realm, he’s long been inspired by real world architecture. “When I went on holiday as a kid I always preferred to see the city rather than spending time at the beach,” Linke explains. “I remember visiting Trieste in Italy and seeing the Rozzol Melara Complex. It was incredibly ugly, but also interesting and otherworldly. It had a huge impact on me.”

Linke would go on to create several games featuring Brutalism, including Fugue in Void, which released last year. “I find there’s something strangely romantic about Brutalism,” Linke says. “The buildings look totally out of place in their surrounding environment. Often they’re forgotten by society or even on the verge of being destroyed.” Brutalism’s detractors have long pointed to the ugly streaks and stains that appear when the buildings are poorly maintained.

Linke thinks part of Brutalism’s appeal, and perhaps the reason for the recent flood of interest, has to do with its purity and minimalism. “The raw facades are hideous, and yet there’s also something aesthetic about them.” Linke explains that the raw, exposed elements, when placed in a virtual context, “make everything look more stylish.”

He also loves the soundscapes that uniquely arise from concrete environments. “I can play with different room sizes and experiment with reverb. Footsteps echoing through the space helps create that sense of exploring a massive megastructure. It’s about fueling the player’s curiosity.”

It’s also about scale. “Buildings that are inhumanly big and engulf the player are inherently mysterious,” he continues. “You can’t build a mental map of them, they’re too massive. That feeling of the unknown — that’s what’s exciting for me.”

Neon Entropy is Moshe Linke’s latest project, and he says it’s his “biggest and most ambitious” yet. With a writer and a programmer on board, it frees him up to focus entirely on the architecture and world building. “I’m spending a lot more time on the details and making the buildings more complex. An aspect I’ve always loved about the Dishonored games are how they open up. You always have multiple ways of traversing the level.” While there looks to be more variation in the environments, Brutalism remains a “central thread” running through Moshe’s latest project.

Neon Entropy is Moshe Linke’s new project, and is influenced as much by Blade Runner as real world Brutalism.

Place-making

Luis Hernandez is one of the creators of Jazzpunk, a comical adventure game set in an alternate-reality Cold War world. While there’s a huge range of architectural styles present in Jazzpunk’s cartoon cities, Luis admits to being particularly captivated by Brutalism, and tries to feature it in all of his projects and games.

Hernandez traces this interest back to school, when he became interested in black and white photography. “Forcing my eye into the viewfinder and looking at the world monochromatically, the structures resonated in a new way,” explains Hernandez. “They became sublime sculptures of light and shadow. My high school itself was built in 1961, and was a good example of Brutalism, as was the nearby University of Toronto and Robarts Library.”

Once again, it’s Brutalism’s purity that captivates. “It’s stark, direct and without ornamentation,” Hernandez says. “After post-modernism, many of us grew tired with giant toys and sprawling plate-glass cages with tacky colour schemes. Brutalism stood quietly. Grey, monolithic markers to a different time. The buildings also don’t try to hide their nature. It’s pure form, light and shadow on display, comparable to something like a classical figure painting.”

While Brutalism can be used to create feelings of estrangement, Hernandez is more interested in its display of raw power. “You can sense its immense strength. The scale and weight alone commands a certain gravitas, but I think this is also why people are often polarised about the style.” It’s easy to see how power and strength might slip into authoritarianism – big buildings make loud statements, but they can also intimidate or even silence.

When designing his Brutalist structures, Hernandez tries to convey a sense of mass, “like the weight you feel when looking at a mountain. It’s unimaginably heavy and exists on a completely different timescale from human life.” While Hernandez thinks Brutalism can be unreliable in conveying things like tension, claustrophobia and horror — there are as many people captivated by it as there are those who believe it an eyesore – he thinks Brutalism is effective at communicating awe-inducing concepts like infinity, alienation and otherworldliness.

But while Brutalism creates powerful emotions, it can’t be divorced from the real-world contexts that gave birth to it. For Hernandez, this history is important. “I use Brutalism to communicate time and place,” he says. “Because it’s not one international style, but an umbrella term for many types of modernism. You can use regional vernaculars to depict different flavours and eras of design. Is the structure municipal, institutional, corporate, part of a campus, military-industrial? Is the building made of cheap gravel aggregate or pure Portland cement? Is the rebar swollen with rust, or the concrete in a state of disrepair?”

Look beyond the simple texture of grey concrete, and Brutalist structures are surprisingly complex. The details are important, and for Hernandez, they help “form a rich tapestry, which hopefully engages players with a sense of place, rather than feeling like just another polygonal game level.”

This structure in Jazzpunk is an example of Metabolist architecture, a cousin of Brutalism that emphasises concepts of organic and biological growth.

Dystopian slide

Solo developer Max Arocena was interested in Brutalism long before he broke into making games. After graduating from architecture school, he spent time digitally modelling many of his more “grandiose” ideas, while simultaneously struggling to make ends meet on small interior renovation projects. “During my off-time, I would sit down and model these formalist structures with no purpose or functionality beyond exploring architectural themes,” Arocena tells us. “Brutalism was a common thread.”

These grand structures would go on to form the basis for Arocena’s meditative first-person exploration game, 0°N 0°W. “The sketches grew until they were large cities that could be explored,” he explains, “so one day I just thought, why don’t I input these into a game engine?” Arocena did just that, importing his project into CryEngine and releasing an early prototype codenamed Dream.Sim.

0°N 0°W features several cities with different styles of architecture. Arocena’s urban environments are closer to what he calls the “playful interpretation of Brutalism, which is about juxtaposing solids in chaotic and non-symmetrical arrangements,” as opposed to more “rationally imposing” forms. He contrasts the irregular shapes of places like Montreal’s Habitat 67 and the Holy Cross Church in Chur, Switzerland, to the more traditional, balanced symmetry of Le Corbusier.

When asked what he thinks people find so fascinating about Brutalism, Arocena’s reply is simple: “power.”

“Power over materials, gravity, nature, but most horrifically, power over people,” he says. “It’s heroic, loud, but at the same time imposing, forceful, oppressive. To me, it’s a symbol of an era that started triumphantly and with the best intentions, but descended into dystopia.”

Brutalist architecture has long been used by filmmakers to explore dystopian ideas, making appearances in the sci-fi worlds of A Clockwork Orange, Gattaca and HighRise. Taken on their own, the buildings can be alluring, but it’s also necessary to consider the negative impact they’ve had on people’s lives. Large concrete buildings are often cheap, uncomfortable, hard to maintain, and can negatively affect our psychology. Used to quickly erect social housing and tower blocks, or for the government to authoritatively mark buildings of civic importance, it’s easy to see why Brutalism has been historically unpopular.

“Consider the daily lives of people forced to live under those oblique, 90 degree concrete angles,” Arocena says. “I think the problem with Brutalism in the real world is that it stopped being an artstyle and became a lifestyle. It tried to solve big socio-economic issues in a very formalist way, which was disastrous! Society and people are organic constructs that continuously evolve, so when you try to prescribe a rigid top-down hierarchy like that, it just doesn’t work.”

The story of Brutalism is that of the organic struggling against enforced rationality, Arocena continues. “While we all want to fit in, we also want to be unique, and this is clearly seen in Brutalist housing units that have survived the passage of time. Occupants change the windows, paint everything in unique colours, hang plants and drapes. In short, they do everything possible to make the space their own.”

A lot of Arocena’s work, like 0°N 0°W, plays with glitch aesthetics, which is a striking contrast when paired with endless mazes of concrete.

The human cost

For Jessica Harvey, it was post-war Britain and the concrete and asphalt that paved over the ruins that influenced the look for her upcoming game, Tangiers. A surreal stealth game inspired by Thief and the literary works of William S. Burroughs and J.G. Ballard, the world of Tangiers is explicitly dystopian.

While Harvey’s careful to avoid creating a pastiche of real world architecture, her environments are still “permeated by real world reflections” – albeit “rendered down to the mundane and unremarkable”. Harvey builds her cityscape by “assembling an aggregate like a collage” — a practice she’s been working on throughout her life.

Harvey’s interested in Brutalism’s “purity of form.” She says, “It’s the culmination of austere protestant sensibilities in confrontation with more traditional, gaudy, adorned movements and attitudes. That’s refreshing.”

But Harvey’s also critical of the movement. “We have a responsibility to go a little darker and take onboard the contexts around Brutalism,” she says, comparing the fascination surrounding Brutalism to the allure of Totalitarian uniforms. “Brutalism expresses control, strength and power on not just the environment, but on surrounding social conditions. It’s a monolithic power project that appeals to many of our base desires, but it’s also impossible to talk about without considering history and politics. It would be grotesquely irresponsible to ignore the origins or the human impact of Brutalism. It caused a lasting swathe of human damage.”

Tangiers: An Orwellian, oppressive-looking governmental building labelled, “Institute of Optimised Consumption Strategies”.

Harvey warns about rendering the socio-economic damage done by British Brutalism down to mere aesthetic. “It would be inhuman to look past the scars. British Brutalism is filled with messy rebirths, failed opportunities and utopian dreams gone astray” she says. “It’s a clear-cut case study on the failings of modernity. We can see how rapidly the opportunity to start afresh without the binds and limitations of tradition can be polluted by corruption, arrogance and systemic incompetence.

“We can also see how much damage this does to those on the lower rungs of the social pyramid. With Tangiers, I’m working to provide a cross section of Britain’s post-war reconstruction. It’s a dissection of modernity and its outcomes. A grotesque rendition of it, but also a frank discussion about the things we take for granted and the mistakes we are repeatedly seduced by.”

Harvey’s point about the seductive power of Brutalism is an important one. While there’s no doubt about Brutalism’s strength – and there are of course plenty of examples of beautiful concrete buildings around the world – many of these structures stem from a very specific time and place. As the style makes the leap to the virtual realm, Brutalism’s history – and its human cost – shouldn’t be forgotten.

A version of this article originally appeared in issue 22 of Wireframe magazine.