Pixel art is back in vogue, but there’s more to its popularity than a longing for gaming’s past, Craig writes.

People forget ‘pixel art’ was once just ‘art’. At least as far as computer graphics can be considered art, which is a can of worms I’m keeping permanently closed by whacking it repeatedly with a mallet. Anyway, for those of us around at the time, there was something magical about seeing blocky approximations of people, spaceships, and household appliances move around in a screen-based world you could directly influence.

As with other media that simplified reality, your brain didn’t question this presentation. No one debated whether Charles M. Schulz was drawing children and a bizarre beagle in his Peanuts comics. And people didn’t prod their tellies, demanding to know why a camel that took their face off in a Jeff Minter shooter wasn’t photorealistic. Your imagination filled in the gaps.

Over time, the rapid evolution of hardware gradually removed technological barriers that forced this graphic style to exist in the first place. Fast forward a few decades, and we’ve moved on from systems barely able to render a few squares to those where the pixels have disappeared into the crisp resolutions of modern displays. Only, they didn’t disappear entirely, because certain developers won’t let them, remaining infatuated with creating games that look like they’ve beamed in from 1985.

But why? The obvious answer is nostalgia – yet that’s not it. Many people who use this style weren’t even born when Bub and Bob first popped a bubble and sort-of Mario partook in a stint of ape bothering.

Instead, when you dig into the non-death of pixel art, you find games creators tend to say it just feels right. Like a musician knows which sounds suit a song, artists know what works for a game. The decision to use pixel art might arrive from personal taste, alignment with a game’s character, or its visual abstraction complementing a given project.

Additionally, pixel art can provide visual clarity and focus; and it acts as shorthand, showcasing dedication on the part of an artist, with players instinctively understanding each dot was deliberately and painstakingly placed. It is, however, now a choice

rather than a necessity driven by technology – an aesthetic that borrows from the past, selected from a vast range of potential options.

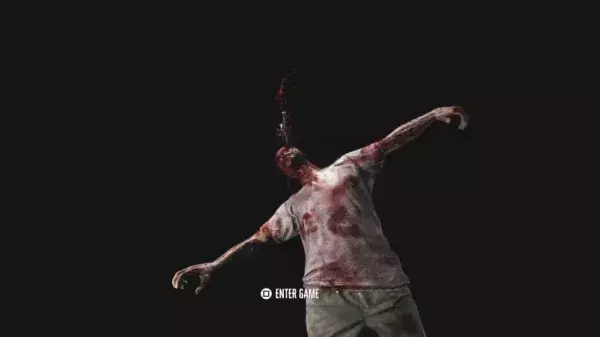

Nonetheless, this, for me, feels like something to celebrate. Being old – although not as old as Mr. Biffo – I found it sad when games were seemingly legally obliged to shift from pixel precision to 3D murk. I enjoyed titles where characters in part came to life in the imagination, rather than barrelling along on a one-way trip to uncanny valley (by way of zombie sporting hell in Virtua Tennis). Any opportunity to go ‘back home’ should bring joy.

Only it isn’t going back home – not really. It’s reductive to suggest those working in pixel art are stealing wholesale from decades past. For one thing, limitations that once defined the style are long gone. That changes the nature of what is produced. Games were once designed for CRT screens. Chequerboard dithering would blend, corners would smooth. Modern displays make for pixel art so sharp you can cut yourself on its edges, and graphics in this style are now designed accordingly.

The result is more remix than recycle – and that’s how things should be. Even when glancing back, gaming moves forwards. Pixel art can be about nostalgia, but that’s never all it is. It’s today part of the increasingly rich visual language of gaming – an ever-expanding toolbox that continues to grow and evolve. It shouldn’t be dismissed as the end product of creators – whatever their age – who have somehow never got over the fact gaming moved on from Jet Set Willy.