The otherwise grim year 2020 marks the 30th anniversary of The Secret of Monkey Island. It’s a game that defined contemporary point-and-click adventure game design and shaped not only its genre, but also how humour, world-building, and puzzles could be interwoven.

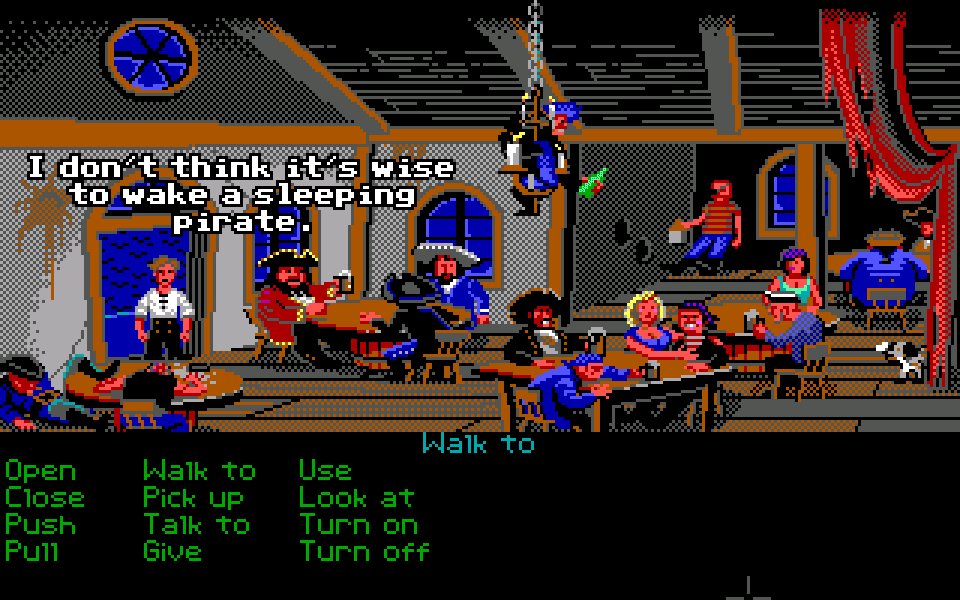

Despite featuring pirate-themed T-shirts and security doors during the era of buccaneers, Monkey Island still managed to conjure a believable sense of place. Its most iconic location was the picturesque and masterfully constructed pirate town on Mêlée Island. This was designed for the EGA graphics format, which only allowed for 16 colours and a resolution of 320×200. Its visuals were the work of Mark Ferrari, who also kindly offered some insights for this article.

MEET THE TOWN

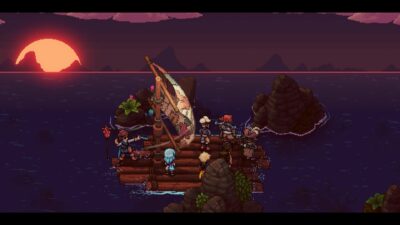

Following the famous opening, where protagonist Guybrush Threepwood introduces himself and declares he wants to become a pirate – suitably, on an outlook above the Caribbean – players walk down a seaside cliff to enter the harbour of Mêlée Town. The first buildings glimpsed are in beautiful, dark shades of blue – most of the game is set at night. The blues of night-time, as Ferrari remembers, worked best under the EGA limitations. Helpfully, four of the EGA format’s 16 colours were shades of blue, which allowed Ferrari, through the use of dithering, to create a relatively rich palette that on blurry CRT monitors almost looked VGA quality.

Past the harbour lie two more scrolling screens depicting the walled core of the town – also presented in blues, and with bright yellow-lit windows – and the whole settlement is bookended by the outlook (leading to the rest of Mêlée Island) and the governor’s mansion (safely situated inland). It’s an elegant, readable, and recognisable structure for a settlement of the time and place, and its limited size feels convincing while also nurturing a sense of familiarity; the town centre was, after all, partly based on real-life references. This town, packed with activities and locations, is a pithy summation of the whole Monkey Island setting.

Though he doesn’t explicitly remember this, Mark Ferrari believes he must have used Rothenburg as visual reference for the downtown.

According to Ferrari, this is a place that feels real predominantly because it’s consistent, not realistic. “You couldn’t do anything realistic with this palette and resolution,” he argues, and there’s admittedly nothing realistic about ghost pirates and vegetarian cannibals. “But this world has rules,” he adds. “Rules about how light and space work in it, and those rules are consistent enough that the world seems believable in itself.” This is how a sense of visual suspension of disbelief was achieved: via the cohesiveness in Ferrari’s work, as he always thinks in terms of systems.

As for the distinctive architectural style of cartoon-like buildings that are narrower at the bottom, Ferrari says they were essentially the result of game designer Ron Gilbert wanting dramatic and interesting camera angles in 2D without having the means to correct perspective as the town’s screens scrolled. It was decided that buildings had to look correct in (skewed) perspective when players stared at the centre of the screen, and thus the style was born.

Exiting the town gates towards the island hinterland leads to the governor’s imposing mansion.

THE PIRATICAL LIFE

Though not a hub in the traditional sense, Mêlée Town is a place that players are meant to regularly revisit during the game, and a core narrative location. The first major quest – the three trials to become a pirate – is given out here in SCUMM Bar, and the finale takes place here in the church. Several puzzles, most major characters, and some of the series’ most memorable locations can also be discovered within the town walls, in a settlement diverse and large enough to support a jail, a piratical store, and the famous International House of Mojo where the Voodoo Lady and a rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle await.

Mêlée Town, of course, remains a setting that has to be complex enough to be interesting, and believable enough to convince players that it’s a living place where diverse locations, and colourful characters can fit in and further characterise it. The richly pirate patrons of SCUMM Bar, for example, are a brilliant introduction to the game’s world.

Inside SCUMM Bar. This is the first place most players will visit, and is packed with jokes, pirates, and lore.

A proper city can’t be static, though. It has to maintain an illusion of activity, and this is why the lights of Mêlée Town’s windows go periodically on and off, and why non-interactable characters walk around using the town’s many doors. “Here’s an example of art and technological limitations defining each other,” Ferrari says. “This was supposed to be a settlement full of windows and doors. We wanted it to feel active with nightlife going on around you, and we didn’t want doors that you couldn’t get in. But if you have doors that open, this suggests you should be able to look inside. And that meant adding, drawing, and storing on disk all kinds of new backgrounds. There was no way we could add six or seven rooms we didn’t need for gameplay. Ron [Gilbert] decided to solve that problem. He decided you should be able to open all doors, and people would go in and out of them, but when you enter any of them, you simply come out (randomly) from another. Though sadly never used for a puzzle, this is a successful way of making the whole town seem real without actually having to show any of it. It wasn’t just the team trying to be funny.”

The EGA Factor

You may have noticed that all screenshots in this month’s CityCraft are not only in a particularly low resolution, but also feature an extremely limited number of colours. Sixteen to be precise; the exact number of colours available to the artists working using EGA (Enhanced Graphics Adapter – the graphics standard superseded by VGA, or Video Graphics Array) back in the late eighties. This palette and its restrictions shaped much of the original Monkey Island’s artistic style and defined its unique, often cerebral beauty.