Jordan Thomas knows a thing or two about generating atmosphere in a video game. Back in the 1990s, he was lead designer on Thief: Deadly Shadows, a game prized for its suspenseful stealth action and world-building.

Under the auspices of 2K Games, he worked on all three BioShock games: he was instrumental in the design of a key level in the 2007 original, served as creative director on BioShock 2, and helped guide the creative flow of the long-in-gestation BioShock Infinite.

In 2013, not long after Infinite’s release, Thomas co-founded the independent studio Question with BioShock collaborator Stephen Alexander. Their first game, The Magic Circle, felt like something of an exorcism: a game about the process of development itself, with its narrative taking in a pair of warring project leads whose ideas flatly refuse to coalesce into a coherent game.

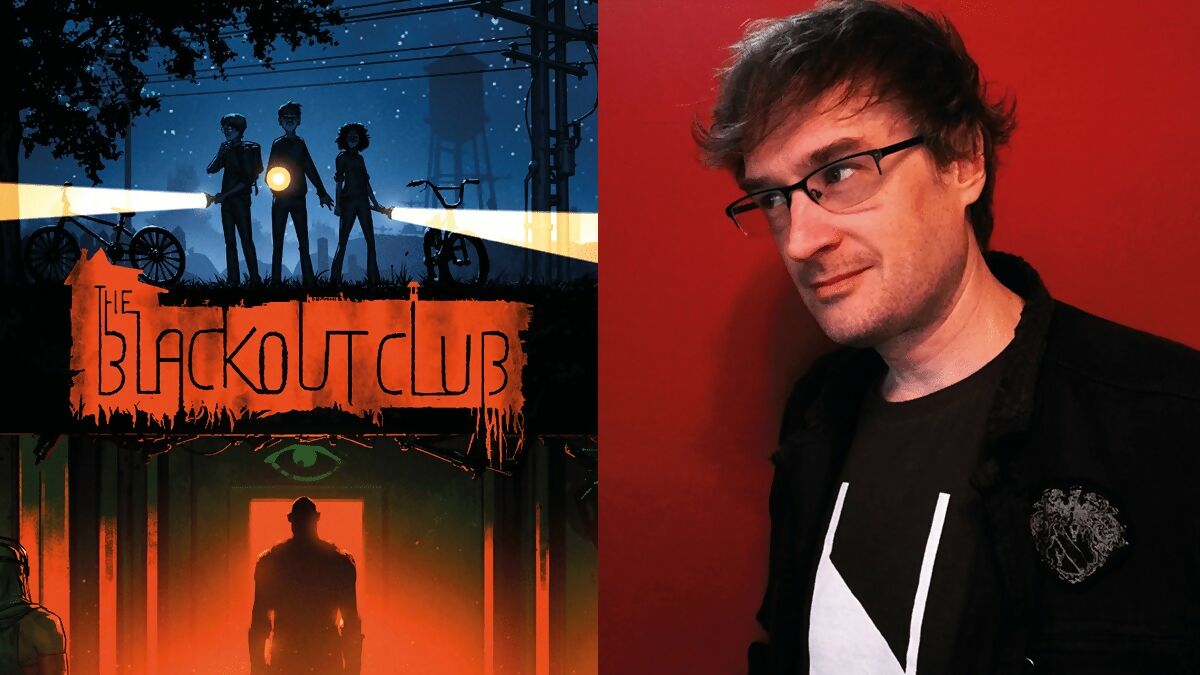

The Magic Circle was a critical if not financial success, and Thomas’s next project at Question feels more broad – maybe even mainstream – in its premise. Taking inspiration from such horror-adventure staples as The Goonies and Stephen King’s It, The Blackout Club is a four-player co-op horror game about a group of teenagers whose small town is being overrun by an unseen supernatural force.

Each night will bring with it a new, procedurally generated mission for groups of players to tackle: you might be rescuing kids from possessed townsfolk one night, or gathering video evidence of the conspiracy another. To better understand the mechanics behind this unique-sounding game, we caught up with Thomas on Skype to find out more.

What was the genesis behind The Blackout Club? Was it the notion of an invisible threat, or was it that you wanted to make a four-player co-op game?

I had a few origin stories, weirdly enough. Way back in 2006, I was working on the universe for this game, and I have been in the background ever since. The sort of urban horror with a touch of fantasy, based on the idea of voices in people’s heads. What they might mean, what they meant historically, and what they might ultimately become. Without spoiling much, that’s the atom that began it all.

But much later, after our first game as an independent studio, which was short-story based and very, very meta (The Magic Circle), we thought, ‘Okay, what is the region of game design and narrative that overlaps with what people are buying these days, that we would still be passionate about?’

We knew we had to go more mainstream than The Magic Circle, but we didn’t want to sell our souls. So co-operative horror felt like the place to find those people. We knew so many people was either too scary for them, too gory, or that they really wished they could bring a friend. I played System Shock 2 cooperatively back in the day when they released a mod for it, and something lit up in my brain: this needed to exist eventually on a more widespread scale.

We also love things like The Goonies, It, It Follows, Stranger Things, all that sort of ‘teens versus the truth monster’, because it’s usually a metaphor for growing up. And all of that seemed to crest at the same time as what we were deciding what to do next, and so The Blackout Club is born out of that.

For much of the game, you’ll be trying to avoid the main enemies: Lucids and Sleepers.

Right. So it’s not an out-and-out gore horror game.

Not at all. Our north star is the word ‘dread’. Ever since my career began, really, I wanted to build horror that lived in the player’s imagination. Their imagination can run wild and they can speculate about what’s around the next corner. So there isn’t a lot of on-screen gore. The invisible boogie man, who we call The Shape, but it has other nicknames too, takes on of them (the kids), he takes them beyond the red door, and what happens there is the source of some mystery, but we want you wondering.

So you’ve got these missions that are procedurally generated, and also you’ve got a backstory. But is there an unfolding narrative that unfolds night after night, or is it going to carry on for as long as the player wants it to?

The current plan is that it’s session based, so it does go on functioning infinitely. You will at some point reach a level cap, so when the game comes out there’ll be a certain number of levels you can get and a certain number of powers you have access to, but the deck — you can keep earning cards in the deck that you use to define your player load-out, and so if you become bored with your level 20 character who’s focused on athletics, you can start expanding into the drone specialist and see what it’s like to play that person.

Meanwhile, we’ll be adding new mission types, which are also like their own adventure deck. We shuffle that and we say, “Tonight is different than last night.” Tonight you’re going to be rescuing kids, and then you’ll segue into a vandalism scenario, where your job is to knock out as many security cameras as possible. If you play the next level 20 mission, you’ll get a different set of objectives. So whenever we add more to the game, they just naturally creep into that set.

It’s interesting you mention those teen horror things, because it sort of feels like those are modern takes on things the weird tales that go back to HP Lovecraft.

Absolutely, yes. That specific cosmic horror genre, and all of its children – existential horror some people call it – but the idea that, ‘You will never truly know the true shape of the thing in the dark’ – your flashlight may glance across it, and that one contour may haunt you to the end of your days. But you’re not going to win – not really. You asked earlier about core gameplay – whether it’s about neutralising or about getting the truth.

Most of the game is centred around exposing the conspiracy, so we’re crawling though these crippled smartphones the kids have. They live in the National Radio Quiet Zone, which is a real place in the States, so they’re unable to get cellular signal, but they have a local version.

So they have to smuggle the footage they accrue out of town of hand. It’s arduous and risky, and kids tend to go missing when they try. Their argument is, “If there are enough of us, then they can’t stop us all.”

“It’s a forensic story,” Thomas says of his new game.

How will you impart those bits of the story? Through third-person cut-scenes?

It’s a forensic story, almost entirely. You’ll be able to acquire narrative as a form of loot, almost – through achieving objectives, you’ll be able to find somebody’s cellphone and see what their last texts were before they were taken. You might hear a voice mail left for the Blackout Club left by someone whose house you might visit later. Our ultimate goal – although there is a single-player story intro which follows the traditions of the Shock games and Dishonored, etc, and sets up the world – from then on, we want the community to drive progress towards more of that. If there’s enough interest in it, and if players are making enough progress, we would like to release more of those, but it’ll come down to a function of interest.

You say that these teenagers are all friends, so how do you establish that connection? That they all care about each other – is that something that’s quite tricky to do in that framework?

A little bit, yes. I’ll try not to spoil the exact context, but suffice it to say that you play one of them, who’s the oldest and the boldest at the beginning, and you learn a little bit about her relationship to the others, and you get to make your own character later – a kid who looks how you want them to look, and customise them with cosmetics you unlock through missions. And they speak to one another in the field, so we got actual kids to record the voices, and they comment to one another, and when there’s a dead spot, they’re likely to say something to one another. When you come back to the hideout, you’ll sometimes hear new comments between NPC kids who are loitering in this abandoned train car in the woods. Very much in the tradition of that cosmic horror genre, you will uncover little bits here and there of what the overall world is trying to say, without ever coming out and stating it.

Stranger Things, Halloween, and a wealth of other American horror influences are going into The Blackout Club.

You said earlier about looking at what people are playing and trying to make something that people are going to engage with. What are your thoughts about stories in gaming? Especially things that are narrative-led – like Bioshock games. Do you think those are falling out of favour to a degree?

Oh, well I think that financially they’ve become additionally risky. I’ve never been a doom-and-gloom prophet who likes to make pronouncements about whether a genre’s over. I think that they fall out of favour for a while and then there’s a resurgence as price points change – for example, we were mired by the $60 disc for a long time, and those games tended to have value packed into them, and air in favour of time in place of player as content machine. So multiplayer, community-driven.

So unless you could sell to that person who only has $60 to spend, this was a machine that makes an experience last as long as they wanted it to. It suddenly started to look like less of a good investment. But I’m very gratified to see that the $60 format is exploding – there’s a million ways to access game content now, whether it’s subscription or a $30 game like Hellblade, where it has these triple-A values, but it’s asking less of you, and it’s delivering this beautiful little rosette of content.

So bringing it back to the point, we’ll never see single-player die, but I do think that that specific thing, of a game that is systems-driven, but has tonnes of story, and is still designed in a series of missions, is becoming a difficult thing for a team to commit to, because they’re selling fewer copies, and there’s more competition for that dollar.

As an indie shop, we had to think in terms of, okay, what’s something that we actually play? And games like Left 4 Dead and Vermintide – any of these games where the characters are actually the players, and the dialogue between them is where the world is discovered — that seemed really fertile to us.

Question is nothing if not interested in what’s next. We’re not trying to jump on a business trend – it’s quite the opposite. We really like to go out of our comfort zone, development-wise, and we hadn’t done multiplayer before, and we hadn’t done a game that wasn’t very talky before – though some of us have. David Pittman, who joined us (as a designer), did Eldritch. I’m a big fan of that game, and that wasn’t very talky at all.

So I’d say we have something in common with that, but in the multiplayer arena.

You’ve come from a background of making suspenseful games. So what’s the philosophy of creating suspense in a game like this? Especially one where you can’t always direct what the player’s going to do next.

Well, I guess I’ll give a two-pronged answer. The first is maybe bone-obvious, which is that the protagonists are vulnerable. I really wanted, directing BioShock 2, to go back to a vulnerable protagonist, but it was a big shooter franchise, and the pressure was to make it a bigger one. So we committed to an action heart, which many others decisions had to follow. I truly loved the early moments of BioShock 1, and the System Shock series, etc, where you’re kind of hyperventilating, and you’ve got maybe one bullet, and you’re leaning around the corner because you don’t know if you can handle what’s there. So some suspense tumbles naturally out of a scarcity of resources.

I guess that segues well into the second economy, which is information. So in Blackout Club, you mentioned the Closed Eyes mechanics, where the kid succumbs to the voice in their head and lets them take control for a second, because it can see things that they cannot. The kids have all been brainwashed to un-see elements of their own town – objects and particularly this entity, The Shape. Once you close your in-game eyes to see it, you’re blinding yourself to everything else, and so you have to constantly be making these trade-offs between which spectrum of information is most important and will lead me to survive right now. You’re frequently wrong. I think there’s a lot of suspense to trying to navigate your own ignorance in that way.

From left to right: Kain Shin, Stephen Alexander, Michael Kelly, David Pittman, Jordan Thomas. Not pictured: team member Jeff Lake.

In that regard, then, what’s it been like showing the game to players and seeing their reaction to it?

Oh my god. Unbelievably gratifying. We went to PAX recently, and we were in a very hidden location. We were worried people wouldn’t find us, but by the second day we had a line out the door. It was because they’d come in in twosomes and foursomes, and they would scream! Their first contact with the experience was everything we’d hoped. I’m not a cocky person – I was anxious on every possible front about how it would be received. I thought we’d get a lot more critique, and I saw a lot of problems that we still need to fix, so don’t get me wrong. But they gave us life – almost literally, watching them go through this for the first time.

Whether it was the single player intro in a couple of cases, or especially the cooperative mode. To hear them speculate aloud to one another – we had one girl who was visibly not a hardcore gamer, but could get dragged into playing cooperatively with her friends. And at some point, she was turned into a sleepwalker by one of the enemies, by the boogie man.

Our guy Steven said, “Don’t forget, everybody, you can rescue her if you want to!” Because she was patrolling around, and you’re kind of like a roving alarm system when you’ve been put back asleep. So he says, “Don’t forget you can rescue her!” And she just says, “Don’t!” Which we thought was incredibly cute, and her friends cracked up. It felt like an emergent moment out of one of these TV shows or books, about a group of friends facing their fears together!

-That’s in the beta video I’ve been watching. There’s this whole morality thing where you can just leave your friends behind if you need to or want to. That’s interesting.

Yeah, and depending on how many make it out consciously, there’s a bonus to the experience you can get, and the loot that you receive in the hideout in the woods.

I see, so you do get a bonus for not being a coward.

Yes, exactly. And there are people who were… the villain of the piece, without spoiling things, is not a killer either. In the sense that it would prefer to turn you into a sleepwalker than to kill you. But if that kid keeps coming back, then you reach a three-strikes scenario where the kid is killed.

We saw some of the players want to carry them all the way out anyway, just for the sentiment of it – no points at all, just picked them up and dragged them to the exit point.

With The Blackout Club, Thomas gets to emphasise more of the creeping dread

we saw in the BioShock series.

So the girl who wasn’t necessarily massively up on games: is this a game that’s fairly approachable for non-hardcore, more casual players?

That’s honestly a very good question, to which I don’t have a glib answer. We’re ever striving to simplify the mechanics that would’ve been appropriate to one of the previous games we’ve worked on, into something you can pick up if somebody invites you to a session and you skip the tutorial, because that’s how a lot of multiplayer games are generated – that word of mouth. ‘No, jump in now.’ And they buy it then and there, and they’re in with their friend. It’s like they fall out of the sky.

For example, we’ve got this power where you point at somebody and they get a prank call, and you can hear Isabella Shaw, the girl from the beginning of the game, say, “Would you like to make more money? We can help with that.” And by the end, she’ll say “You’ve just been pranked by the Blackout Club.” It has to be as simple as, I point at someone and hit the right bumper or the middle mouse button, and they stop in place. Because if it isn’t that simple, then they can’t experiment and tease it out.

The strategic use of it, through exposure and repetition, they start to use it more elegantly. But the core has to be instinctive and immediate. But we went through many iterations where we cut tools that were too tweaky because it was inappropriate for co-op horror.

You’re a team of six, is that right?

We are, but with some really legendary contractors. So Sam Gauss, a UI contractor, came in and made the game look a lot better. Patrick Balthrop worked on all the BioShocks with us, and he is our audio specialist, and the list goes on. So I’d say that realistically we’re talking about the labour of more like 10 people plus some volunteers and things like that. But yeah, six full-timers.

Missions are procedurally generated, so each night’s horrors are different.

So going from those big triple-A games to a small team like this, what are the advantages of that?

Agility, primarily. I know every member of our team, we can have a conversation like humans, without hierarchy, needing to be an overt element there. Three of us are still co-owners of the shop and there are times when I have to break a tie. And they’ve actually asked that I break a tie in that case. But it seems, frankly, like the game: a group of friends solving a complex problem than it does the structure I worked in previously.

We’re also able to make changes very quickly if there’s a playtest. If we see that something is wrong, there is not a lengthy debate, there’s no running it up the chain, it’s just “Let’s fix this.” It’s often done by the end of the day. That part of it feels good.

On the other hand, we’re constantly starved for resources, and when it comes time to promote the game, we’re split between making actual fixes to it and trying to do things like this, frankly, right? That combination is often hard to navigate, but I wouldn’t trade it. I think that each of the team members has different strengths, and we naturally found the things that we’re best able to optimise our time for. I may change my tune – once the game is live, we might be split in an entirely new way. But we’re running closed betas right now and they’re going very well. So I’m hoping we can keep coasting on that goodwill for a bit!

It sounds freeing, that you’re making things that are more personal. The Magic Circle was about your memories of triple-A game development, and this one could be about an indie game developer being a close knit team facing the unknown.

Yeah. As you say, we don’t use that analogy very often, because The Magic Circle is so much more nakedly about game development. But yes, our friendship on the team is very important to us. When there is any friction, it kind of rocks us a little bit. We’re not an argumentative bunch. Strong-willed and vocal, but we don’t fight that often. I sometimes wonder if we don’t fight enough. But that feeling almost a bunch of college friends tinkering on a project together has not ever fully gone away. And again, that might at some point have to – I don’t know. Companies have their own cycle of growth, and no relationship is immune to change. But right now I’m very much enjoying how liberating, how freeing it is to work with a small group of people I trust so well.

A condensed version of this article appears in Wireframe #2, available now. The Blackout Club is scheduled to launch on Steam in 2019.