In 2011’s L.A. Noire, the female characters with real agency are outlaws, outright villains, or at the margins of society.

NB: The following contains spoilers throughout. If you haven’t already, we recommend playing L.A. Noire before reading.

Play the 2011 thriller L.A. Noire without critically thinking about it, and it would be easy to write off characters like Candy Edwards. A young woman who’s murdered while attempting to leave Los Angeles with a bundle of cash taken from various betting shops, Candy might be dismissed as just another lowlife who paid for their avarice instead of striving to make an honest dollar. But when you critically examine the game’s rich layers, it becomes abundantly clear that the women with the most agency in L.A. Noire are all criminals. If they’re not committing crimes or abetting men who do, they have no interest in being prim and proper housewives.

There’s plenty of other instances where women are used as tools, like Jean Archer in the case, A Slip of the Tongue, and Tomoko Okamoto in Nicholson Electroplating. They serve other parties but have agency in their actions, only to wind up in jail and a body bag respectively. June Ballard in The Fallen Idol horrifically arranges the rape of her teenage niece for her own selfish purposes: to blackmail a perverted director into giving her a movie role.

Julia Randall in The Naked City proved to be more than just a pretty model – a job that provided a rare, steady line of work for women back in the postwar era. Interviewing Dr. Stoneman reveals that Julia had a substance abuse problem like many women did when they traded their wartime jobs for suburban housewifery. But Julia leads a burglary ring with con man Henry Arnett. He poses as a successful entrepreneur who fences stolen goods from the wealthy to finance his habit of sleeping with models, but Julia’s the one who ultimately calls the shots.

Read more: L.A. Noire | Why it’s a staggering portrait of misogyny in postwar America

Henry isn’t too happy about Julie deciding to make a name of her own in crime, since she’s aware she won’t be able to model and accept gifts from horny rich men forever. Heather Swanson, Julia’s co-worker, is an unwitting accessory for Henry to mooch off of and use as a tool after he swept her off her feet with one delusion after another.

Candy and Julia aren’t just tools used by men who are subsequently punished for acting in their own interests. They used their beauty and intelligence to survive as best they could in a time when women didn’t have many other means of supporting themselves. By contrast, the wealthy and powerful men behind the Suburban Redevelopment Fund – arguably the game’s true villains – threw their humanity into a wood chipper long ago. Candy and Julia therefore serve as foreshadowing to the revelation of the Suburban Redevelopment Fund’s investors and greedy intentions.

Interestingly, though, the woman with the most agency in L.A. Noire doesn’t end up dead in the pursuit of financial independence and autonomy. That would be nightclub singer Elsa Lichtmann.

Star-crossed lovers

Credit: Rockstar Games.

As with everything else in L.A. Noire, there are complex layers that its writers intentionally and unintentionally fleshed out through the characters of detective Cole Phelps (Aaron Staton) and Elsa (Erika Heynatz) – the narrative’s star-crossed lovers.

Countless fan theories and discourse about the intricacies of L.A. Noire’s complicated multilayered plot abound, with many fans puzzled as to why they pursued each other. But when you closely examine both Cole’s and Elsa’s characters and the context of the postwar era, their relationship makes perfect sense.

First, there’s much foreshadowing about Cole’s marriage. A detective colleague, Bekowsky, gets him to admit he’s attracted to blondes and – on the rare occasions where she appears – we see that his wife Marie is a brunette. Cole’s partner Rusty drops hints that lurid homicide cases put a strain on detectives’ marriages. When you’re still on the traffic desk investigating how Adrian Black faked his own death to leave an unhappy marriage and start over with the secretary he was cheating with, it’s the mistress who kicks him out and Mrs. Black who takes him back – prompting Bekowsky to remark that she must have poor self-esteem.

Cole is clearly attracted to women who stand up for themselves, but little is known about Marie. We only see her three times in the entire game: briefly in the intro, when she kicks Cole out of the house after she’s harassed by reporters about his affair, and at his funeral where she’s entirely stoic. It’s Elsa who becomes vocally emotional.

Marie is referred to a few times by other cops, but is almost never mentioned by name. Even for all of Cole’s progressive values, he keeps mum about his family life and isn’t a “wife guy” as one would be dubbed in the 2020s. He simply refers to Marie as “the mother of my children”. She’s just an accessory, as a wife was often viewed in this era. This could also be construed as Cole wanting to keep his family separate and safe from his increasingly dangerous work, but once Cole becomes embroiled in the corruption he’s unveiled, and slowly realises how he’s indirectly responsible for the hideous events that began with his tour of duty in Okinawa and the subsequent heist aboard the SS Coolridge, he hits a point of no return. By now, his investigations have consumed his life.

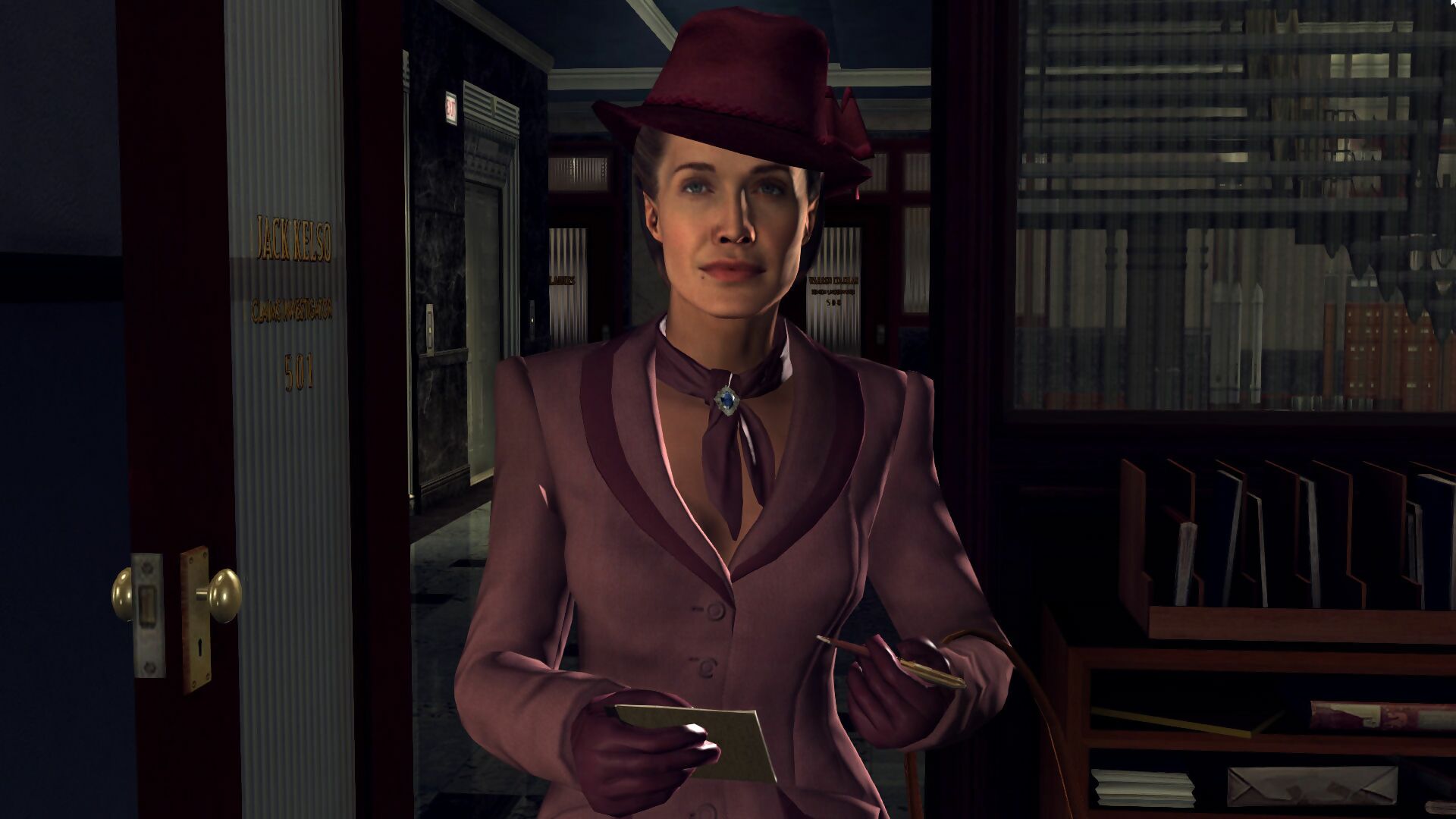

In yet another whiplash of heel-turn foreshadowing, Cole’s first encounter with Elsa isn’t the most welcoming: she calls him a fascist since she doesn’t trust the police. It even looks as though she’s being used, just like the other women in L.A. Noire – at least at first. The deadly quack Dr. Fontaine gives Elsa morphine when she’s grieving the loss of a close friend because the club manager wants her drugged so she’ll perform. Elsa even addresses the gendered violence she’s faced all her life – violence that women were expected to tolerate in the 1940s – claiming that her friend Lou was the only man who never laid his hands on her… and detective Roy Earle immediately does just that.

Credit: Rockstar Games.

In the chapter Manifest Destiny, the interrogation at The Blue Room ultimately lays Cole and Elsa’s attraction bare. Cole is attracted to her because she challenges him intellectually in a way that Marie likely does not. Her perspective has been coloured by fleeing a fascist regime following the deaths of her family and friends in Germany. She’s a refugee but viewed as the enemy. In coming to America in the name of safety and freedom, Elsa loses another dear friend to capitalist greed and becomes part of the underworld that the so-called upstanding citizenry of postwar LA look down on: a nightclub singer who spends most of her time with Black jazz musicians.

With proper context for how racist and xenophobic society was at the time, this was pretty risky for a white woman in 1947. It was even riskier for the Black men around her, despite their relationship being mostly professional. Nevertheless, Elsa challenges Cole’s worldview. She queries whether he wants to mindlessly carry out police procedure or actually make the world a better place as he suggests. Why fight a war on drugs instead of the hardships that cause people to seek drugs in the first place? Deep down, he knows she’s right. He’s far from a rose-red Democratic Socialist of America, but he doesn’t fit in with his predominantly conservative, racist, and misogynist cohort, either.

Cole’s an educated and fairly enlightened man. It’s no surprise that he’s turned on by smart women who aren’t interested in serving men or authority. In turn, Elsa sees that he’s a genuinely caring and protective person at odds with Roy Earle and the powerful forces who have him on their payroll. Yet of all the moral bankruptcy revealed, Cole’s infidelity is scorned more than extrajudicial murder and deeply-entrenched corruption.

Credit: Rockstar Games.

Cole’s golden boy status was always going to be called into question at some point. He was ironically put on the same pedestal that many women are placed on, where a transgression erases all of his skills and accomplishments. The affair he initiates was also meant to make the player question whether Roy and the dark sides of LA corrupted him. And if he’s corruptible, doesn’t that mean there’s no hope left?

Cole isn’t just demoted after Roy snitches on his affair with Elsa. He loses his place in the white male hierarchy when he’s charged with adultery and his wife leaves him. He’s lost an accessory that signals he’s higher up the patriarchal pecking order.

Mediocre white men vie to keep their place at the top of that hierarchy, and Cole lacks interest in propping it up – despite initially having a high place within it. If anything, he’s well aware of his mediocrity. The war flashbacks reveal that he was a pretty incompetent leader despite making a great detective when he came home.

Even though Cole has strong morals and feels guilt about what happened in Okinawa, look who’s truly running the city and the order they want to maintain. Rusty and Biggs openly state how they barely bother to investigate cases of murder and arson. Then another mediocre white man’s career and identity must be protected after Cole finds and kills The Werewolf, while other men are tried for murders they did not commit.

Cole’s death is willful suicide, ironically dying by water after the fires. He ultimately chooses this demise out of guilt over the horrific events he was involved in during the war. The guilt from his affair, in spite of his true love for Elsa, only compounds his decision not to fight the tide.

I started playing L.A. Noire thinking it would be an example of copaganda, but was surprised to find a major indictment of hegemonic institutions. The game becomes a critique of capitalism by the denouement, whether it intends to be one or not.

People have misplaced nostalgia about the postwar era because they were led to believe life was as wholesome as the movies produced under the Hays Code, and there’s a strong chance their older relatives didn’t tell them the entire truth about life in those days. L.A. Noire pulls back the curtain and shows there was plenty of sex, swearing, and seediness – and that the 1940s was a horrendous time to be a woman.

Read more: L.A. Noire | Why it’s a staggering portrait of misogyny in postwar America