It’s a mere twenty years since Nintendo’s final Famicom console was manufactured in Japan. We look back at the many curious differences between it and its western cousin, the NES.

When Nintendo launched its first ever home console, the Nintendo Entertainment System (or NES) in Japan on July 15 1983, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were the leaders of the free world, and Emperor Hirohito was still alive.

By the time the final such machine was manufactured, 20 years ago this week on 25 September 1983, the machine had outlasted the Soviet Union, apartheid in South Africa, and the existence of the Twin Towers. Two full decades was an amazing lifespan for any video game console. It’s fair to say the NES was quite popular in Japan, then.

Except, of course, the NES was never technically released in Japan at all – the market-leading, industry saving, 8-bit home console Nintendo sold there was actually called the Famicom, short for ‘Family Computer’, and it was a very different beast from the sister-device the Kyoto games giant sold abroad. But different in what precise ways? Different in the following precise ways, that’s how…

The Family NES: Name and appearance

Why was the Famicom called the Famicom in the first place? Originally, it was going to be called the ‘Gamcom’, or ‘Game Computer’, but the hardware’s chief designer, Masayuki Uemura, had a wife who thought ‘Family Computer’ sounded more wholesome and appealing. Family Computer was soon shortened to ‘Famicom’, but for years, this was nothing more than an unofficial nickname – largely due to Sharp already having the rights to use a similar name for a line of microwave ovens. It wasn’t until the emergence of the Famicom Twin System (see later) that a Nintendo device would officially carry the shortened name it was so popularly known by.

The NES moniker, meanwhile, adopted for the US, Europe and elsewhere, was specifically designed to make it sound like something other than a pure video games machine. In 1983, the very year the Famicom appeared in Japan, there was a major crash in the gaming market in America, leading many there to think the medium had died forever, making the phrase ‘Nintendo Entertainment System’ sound appealingly vague and non-specific, as if it were some sort of multimedia device.

Indeed, the US and European unit was specifically designed to look like a VCR. Unlike the Famicom, which had SNES-style top-loading cartridges, the NES was a front-loading device, thought up by US-based designer Lance Barr, and based upon a Zero-Insertion Force (ZIF) concept. As video-recorders were highly popular Stateside by 1985, when the NES finally launched there, Nintendo thought this model would subliminally reassure customers this was not just yet another junk console-brand which was going to go bust about five minutes after launch.

Ironically, however, the front-loading ZIF mechanism didn’t stand up to use; repeated swapping around of games bent the connector pins back slightly over time, meaning your NES would eventually stop loading its software reliably. Playground lore had it this was due to dust on the pins, and that blowing on them would cause it to work properly again – but this really only led to mouth-moisture corroding brass and nickel inside the machine, making the situation worse.

Japanese Famicom gamers had no such problems, with their fancy top-loading console, making games and machines alike last longer. They also got a handy ‘Eject’ button to use, although it wasn’t actually necessary – games could safely just be pulled out by hand. The button was only added at the suggestion of Nintendo design legend Gunpei Yokoi, who thought kids would find such a mechanism fun to play with by itself. Even when turned off, the Famicom was supposed to be a fun toy for all the family, like a toaster (legal note: please do not allow your family to play with toasters).

Famicom cartridges were also much smaller than their NES counterparts – NES carts were far larger than they practically had to be, being substantially just empty plastic, but super-sizing them for the Land of the Free was supposed to subconsciously suggest to purchasers that the actual games inside were larger or more powerful than they really were. Famicom carts were more colourful, too, each coming in its manufacturer’s own chosen shade of bright shaded plastic, as opposed to the dull uniform grey of US NES carts (golden Zelda games aside). Japanese carts were also horizontal landscape-format, like SNES ones, not vertical portrait-format, like NES ones.

Even the machine’s central base-unit itself was more colourful than the two-tone-grey-with-a-little-stripe-of-black NES, the Famicom coming in a main shade of off-white cream, offset with several maroonish-red trimmings. The choice of Japanese colour-scheme is generally explained in one of two ways: either company President Hiroshi Yamauchi’s favourite scarf happened to be maroon and cream, or else he saw a billboard using these same shades on his way into work one day, and decided he liked them. Whatever the truth, the real message is this: it was Yamauchi’s company, and anything the notoriously fierce corporate overlord said went, otherwise you were ruthlessly and instantaneously sacked (just ask Gunpei Yokoi …).

The Famicom was also noticeably smaller than the intentionally bulky NES, although of course deep inside, their internal architecture and CPU were basically identical, as you would expect. Some sham consumer psychoanalyst could probably get an entire essay out of purporting to explain what this reveals about the innate native psychologies of boastful, in-your-face 1980s America compared to more reserved and self-effacing, polite Japan – although any such analysis might well ignore the simple fact that, due to crowded cityscapes and high land prices, Japanese living-rooms and bedrooms simply tend to be much smaller than the average western ones.

Blowin’ in the wind: controllers and microphone

One advantage the NES has over the Famicom lies in its controllers: they are detachable, with much longer leads. Partially for cost-saving reasons, and partially due to presumed limited living-space amongst Japanese consumers, Famicom joypads (which are gold and red, with black buttons, unlike the nicer-looking and now iconic NES ones) were wired directly into the console itself, having to be stored away in little grooves in the base-unit’s side when not in use.

However, Famicom controllers had at least one undeniable extra selling-point over their Western NES counterparts – the second one came with an in-built microphone for use during gameplay instead of the more usual ‘START’ and ‘SELECT’ buttons. Only around a dozen games out of a library of 1,000-plus titles ever actually used the thing, but the option was still there for developers to use it if they really wanted to.

Nintendo’s intention was to capitalise on the karaoke boom sweeping Japan at the time, but the development of any actual karaoke title was rather stymied by the mic’s exceedingly limited functionality. Quite simple in nature, it could detect sound being made into it, but never recognise what that sound was.

Consider its application in the Japanese version of Kid Icarus, where, when your character Pit entered the in-game shop, the player could pick up the second controller and haggle into it, forcing the merchant to lower his prices. “£200!” you were supposed to shout, meaning maybe he would reduce the price from an initial £300 for a magic potion to a more reasonable £250. In practice, you could just shout anything into the mike and it would have the same effect: blowing into it worked particularly well. It would be surprising if some Japanese children didn’t just fart into the controller to see what would happen: presumably, the poor shopkeeper would immediately give away his wares for free, simply to make it stop.

When games which did actually make use of the microphone were later re-released in the west, they had to be slightly re-programmed. The Japanese version of The Legend of Zelda contained large-eared rodent enemies called Pols Voice. As they had such huge ears, if you screamed/blew/farted into the microphone, their aural oversensitivity made them all explode and die immediately. This option was not available to mic-less Western NES losers, however, so Nintendo’s programmers compromised by making the big-eared beasties extra-weak to attack by arrows instead; something which makes rather less conceptual sense. They should have redrawn them with archery targets on their foreheads or something.

Disk-combobulation: peripherals and add-ons

Another difference between NES and Famicom is that the latter came with an extra connection slot for peripherals on the front right-hand side of the unit – which could easily be used to plug in an extra third-party controller for three-player Bomberman sessions, if you liked. Alternatively, you could slot in a special cream-and-red-coloured keyboard to finally turn your Family Computer into an actual computer, if you saw fit – and many Japanese gamers did, with 400,000 sets of something called Family BASIC being sold by the end of the 1980s.

Released in 1984, Family BASIC was a simple home-programming kit consisting of a keyboard for input, a cartridge pre-loaded with a Nintendo-ified variant of the popular BASIC programming language suite, and a cassette-tape recorder to save your finished games on, as with an old Commodore 64 or ZX Spectrum of the day. One early purchaser was none other than Satoshi Tajiri, later the creator of Pokémon, who made his first ever foray into programming using Family BASIC, the puzzle game Quinty/Mendel’s Palace. As Pokémon’s incredible Game Boy-era profits essentially saved Nintendo from ruin during its late-1990s fallow period, the company’s initial, forgotten foray into facilitating home-brew game-making may actually have been one of the most significant moves it ever made: a real-life version of the plot of Wario Ware: DIY.

Less successfully, the Famicom even had its own 3D VR headset-glasses unit, the Famicom 3D System. Released in 1987, it only gained seven actual compatible game-releases, and sold even more poorly than the later equally doomed Virtual Boy, which is saying something. A Famicom Modem appeared too, connecting game-playing salarymen up to a database featuring live, up-to-date financial information for them consume in-between their next all-night Bubble Bobble sessions.

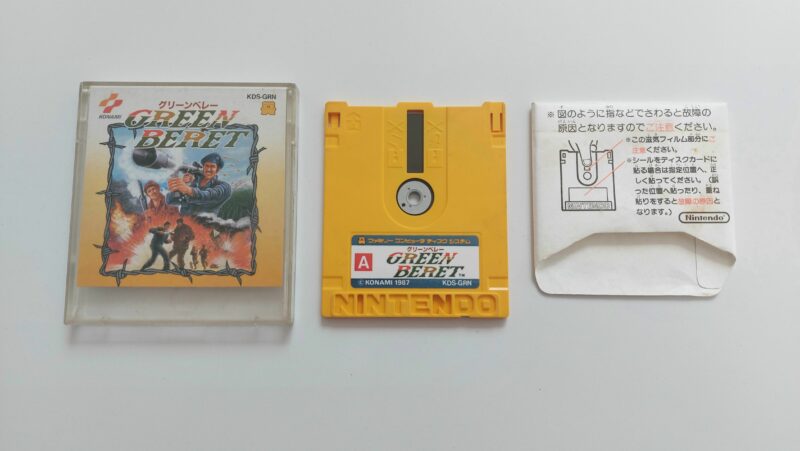

Most significant of all was the Famicom Disk System (FDS) add-on, an early precursor to later such console extensions like Sega’s Mega CD and 32X and Nintendo’s own 64DD, except this one was actually somewhat commercially successful. When first released on the market in 1986, the FDS made perfect sense: due to cost-considerations, storage capacity on carts was small indeed, and there was no such thing as battery back-up, making saving your game impossible. By releasing a second base-unit to which your initial Famicom base-unit could be attached, enabling it to receive rewritable, PC-style floppy disks in special, hard-plastic caddies, both these problems were immediately solved.

This was great news for gamers, as it enabled entire new genres, chiefly the JRPG, to be developed for home-console use. Following high early sales, Nintendo decreed that, from this point on, all first-party titles would be FDS-format exclusives: including a little FDS launch-title called The Legend of Zelda. Other classic much-loved Nintendo series to make their debut on FDS disks included Kid Icarus, Metroid and Konami’s Castlevania.

But … all these games were also available in the West on normal NES cartridges, weren’t they? Yes, because, almost as soon as the FDS was released, it was more-or-less obsolete. The disk-format brought several genuine advantages. Sound-output could be superior (compare the Japanese and Western versions of Castlevania III for proof). Production costs were certainly cheaper, meaning far lower prices for consumers, too (and lower profits for manufacturers and retailers, which they didn’t necessarily like).

Also, as they were rewritable, FDS disks could be taken into stores and slotted into kiosks, which functioned rather like juke-boxes, being pre-loaded with the latest releases for customers to copy onto their blank or wiped disks for a smaller fee than buying games brand-new in a box. These ‘Disk Fax’ machines could even be used to upload players’ hi-scores into to be sent off to Nintendo HQ in Kyoto, to win prizes like Nintendo-branded stationary or a golden Punch-Out!! cartridge (or a golden-coloured one, anyway).

Sadly, due to poor design-choices, the disks could easily become scratched, dirty or demagnetised, rendering their data corrupt and unplayable; they were also vulnerable to pirating, something which made Nintendo wary of using CDs or DVDs as storage-formats right into the N64 era. Furthermore, elastic bands used inside the main unit would actually melt over time, breaking the FDS itself: now Japan too had a taste of the West’s own ‘Broken NES Syndrome’. Fortunately, you could buy a proprietary two-in-one Famicom and FDS unit in shape of the ‘Twin Famicom’ made by Sharp, which may not have suffered this particular elastic flaw (Sharp also made a 14-inch ‘C1 My Computer Famicom TV’, with the base-console built directly into it, for the truly space-starved gamer).

More seriously, not long after the release of the FDS, cart-stored battery back-ups began to appear, making save-games possible without disks, while drops in price of memory made larger games feasible on carts too. Now, ordinary Famicom cartridges became able to store more data than FDS disks could, rendering the add-on format’s main original advantage null and void; the FDS maximum was 112KB, but a mere four months after launch, Capcom released its Ghosts n’ Goblins arcade conversion on a 128K cart. Given all this, Nintendo’s planned Western release of the FDS peripheral was dropped in favour of just porting its best games to cartridge format after all and releasing those in America and Europe instead.

Nonetheless, aided by its cute mascot Diskun (‘Mr Disk’), a cute yellow FDS diskette with eyes and tiny, nub-like limbs, the Famicom Disk System still managed to sell 4.4 million units, making it the most successful main console add-on unit ever made – albeit 2 million of those were in its first year on sale, before everyone realised it was already out-of-date immediately after being born. Indeed, the FDS spin-off actually outlived its parent Famicom by five whole days, with its ‘Disk Fax’ disk-writing service only closing down for good on 30 September 2003.

The final Famicom itself, serial number HN11033309 (nothing to do with swine-flu), was kept by Nintendo themselves as a memento. But don’t worry, you can still fairly easily pick one up second-hand online: by 1989, just before its successor the Super Famicom/SNES was released, it was estimated 37% of all Japanese homes had a Famicom sitting under their television set, so it’s not as if they’re terribly rare items.

Of course, the main notable difference between Famicom and NES was in their respective software libraries – but more on that in the second part of this short commemorative series.