Three decades after its original release, Zombies Ate My Neighbors remains surely the greatest B-movie-themed videogame of all time.

The mid-1990s were a great time to be a fan of comically dire, horror-themed B-movies. There was Tim Burton’s charming 1994 biopic Ed Wood, in which Johnny Depp played the titular angora sweater-wearing director of such low-grade fare as Plan 9 From Outer Space, supposedly the worst film ever made. Then there was enthusiastic young TV star and cinema-obsessive Jonathan Ross, who kept British small-screen viewers equally entertained with his fondly-remembered Incredibly Strange Film Show and its 1995 follow-up series, Mondo Rosso.

Every Friday after midnight was horror film night on both BBC and Channel 4. From 1960s and 70s Hammer horrors starring Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing as Count Dracula and Professor van Helsing, to 1950s sci-fi flicks with amusingly lurid titles like Devil Girl From Mars, Cat-Women Of The Moon, The Killer Shrews and Attack of the Crab Monsters to weird Japanese kaiju monster-mashes like Terror of Mechagodzilla, fans of utter filmic trash (and the occasional genuine cinematic gem) were well catered for indeed.

16-bit zombies

Videogame fans of this period needn’t have felt left out, because in 1993 a title was released for the US versions of the SNES and Mega Drive by LucasArts and Konami, bearing the equally sensationalist moniker Zombies Ate My Neighbors – a title later sadly shortened to simply Zombies in Europe, after local bowdlerisers protested the original name may prove corrupting to the continent’s supposedly vulnerable youth. Some of the blood and chainsaws were also removed from the European version of the game – replaced by purple gunk and massive axes, which were obviously much less violent and disturbing.

Even the box art was censored. The US release contained stock black-and-white photos of a screaming blonde menaced by a group of shambling zombies straight from George A Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. The European version, by contrast, featured a more cheerful comic book image of the game’s two teenage heroes, Zeke and Julie, bouncing up and down on a big trampoline in the middle of a garden while an army of cartoon zombies – who looked strangely like the late English philosopher Bertrand Russell – emerged from the ground, arms outstretched. Both still carried the shared slogan “55 Un-Deadly Levels!”, however (well, not the Mega Drive version, as it couldn’t fit 55 levels on the cart).

At the back of the instruction booklet for the SNES version (which was the better game, having not only more levels, but also superior graphics and controls and a hidden flamethrower Wunderwaffen weapon included), the developers listed a number of alternative titles which had been discarded prior to final release. To judge by how awful they were, the LucasArts employees should actually have been working for the 1950s US B-movie industry for real: The Zombies’ Wrong Turn At Alpha 6, Suburban Zombie Bake-Off, Return of the Teenage Son of the Bride of a Zombie, Part 2 and even the frankly unacceptable Ghouls Just Wanna Have Fun.

Film references and terrible puns just kept on flowing in the actual level titles, announced in blood-curdling horror-fonts prior to each new area, too: Dances With Werewolves, Nightmare On Terror Street, or Mars Needs Cheerleaders!, a nod to the legendarily abysmal 1968 TV movie Mars Needs Women. The only shame is that one of the several factory-set levels filled with crates of newly-manufactured axe-wielding devil-dolls wasn’t christened I Was a Teenage Warehouse.

Monster mash-up

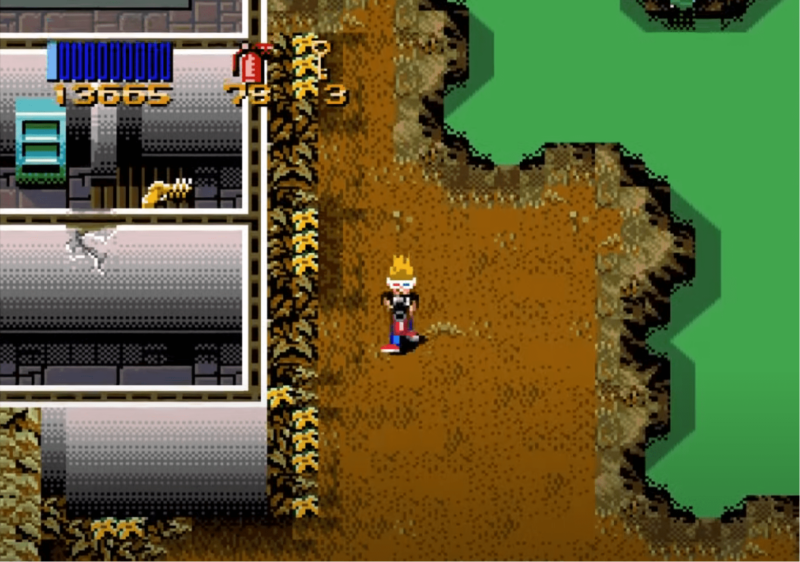

The game itself was a top-down 2D run-and-gun, similar to Robotron or Smash TV, of which the designers were big fans. Zombies Ate My Neighbors, however, altered the formula in several even more winning ways.

Each of the 55 (or 40-odd if you had been gullible enough to buy the Mega Drive version) levels was a maze, filled not only with the undead, Martians and other such beasties, but also up to ten unsuspecting potential human victims for the monsters to find and feast on – the ‘neighbors’ referred to in the original US title.

A stereotypical mad scientist, Dr Tongue, had busily manufactured all the monsters in his secret lab, before unleashing them on 1950s America, just for the fun of it (although actually he was working at Konami’s specific behest; before they acquired the game from LucasArts for worldwide publication and demanded it be given a basic plot, the title had no Dr Tongue, the monsters just appeared for no reason).

As the only two kids on the block who actually realised what was going on, it was your job as either Zeke (a boy wearing a pair of those old cardboard 3D glasses) or Julie (generic girl in a red baseball cap) to race through the levels rescuing as many innocent babies, cheerleaders, archaeologists, trampolinists and cowardly, shivering soldiers as possible before the zombies and mummies got them first, at which point you could exit to the next maze.

First on your priority list should have been any pairs of gawping, photo-snapping tourists: some levels featured a day-to-night mechanic, and when it reached midnight, said tourists transformed into werewolves with a loud off-screen ‘Awooo!’

The number of neighbours you had left at the end of every level carried over to the next stage, and when this number reached zero, you were dead – if the player-character wasn’t dead already anyway, after being fanged by a vampire, drowned by a gill-man, or chopped to pieces by an axe-murderer in a hockey-mask.

Destroy All Monsters!

The game was mainly set in 1950s suburbia and allied locations like high-school American Football pitches and zombie-infested shopping malls akin to that from Dawn of the Dead, albeit with occasional diversions into haunted Gothic castles, Egyptian pyramid-tombs and creature-ridden mineshafts. Most of the weapons you had to collect from household cupboards orjust lying around in people’s gardens were ordinary everyday domestic items not normally thought of as being deadly at all.

Your standard firearm was an Uzi-shaped water-pistol filled with holy water, which was excellent for taking down the weak zombie hordes with a single squirt, but next to useless when combatting, say, a werewolf. When confronted with such furry therianthropes, you needed to change tack and hurl cutlery at them instead, which would cause them to shed their pelts and expel their unclean, green, Slimer-like souls with a single hit – said cutlery being silver-plated.

Some of the enemies’ weaknesses make sense – alien pod-plants and mushroom-men being vulnerable to lawn-strimmers, for instance – while others just had to be discovered by trial-and-error. Who would ever have guessed Martians were allergic to tomatoes, or that possessed toy dolls would burst immediately into flames when you hurled a shaken-up six-pack of soda cans at them in an explosion of fizzy goodness? A familiarity with actual old B-movies could help you out at times, too: lobbing lolly-ices at big sticky red blobs caused them to shatter to death instantly, as freezing was how the original such extraterrestrial red blob-beast was once defeated by Steve McQueen in 1958 scream-fest, The Blob.

The great variety of weapons is actually a little awkward. Fleeing werewolves while desperately cycling through your arsenal until you reach your cutlery ammo is exciting, but in the heat of the moment it’s exceedingly easy to cycle straight past the knives and forks and have to begin the process again, by which time you’ll probably have been clawed to death. It might have been better to map cycling backwards and forwards through weaponry to the L and R buttons respectively, to be more forgiving; the neighbour-locating radar mapped to L and R alike could easily just have been pulled up or down on-screen with a simple tap of ‘select’ instead.

The other weaponry-related problem comes with the slightly useless in-game password system. The developers originally wanted to include a battery back-up save-game option, but cost considerations decided otherwise. Therefore, passwords served as a cheap alternative. The problem was, these passwords only recorded what level you had reached and how many neighbours you had left: all your accumulated weapon inventory was wiped, leaving you with little more than a half-empty water-pistol to take on the ultra-hard monstrosities lurking in the latter half of the game.

A big part of the title’s appeal lay in inventory-management. If you didn’t save enough bazooka shells and magic potions (which transformed you into a hulking great invincible purple hell-beast, Jekyll & Hyde-style) for use later on during the much easier first half of proceedings, then by the time you were being assaulted by giant worms and colossal tarantulas, you hadn’t a hope of completing the game. This would have been a shame, as the credit sequence was a separate level by itself, where you ran through a cobweb-infested office, meeting all the developers sitting at their desks in LucasArts HQ – even George Lucas is there in pixellated form.

Invasion of the Copyright-Snatchers

These minor blemishes aside, the game possesses otherwise exemplary mechanics and exceedingly high replayability value, being the very definition of a cult classic. A huge part of its appeal is aesthetic. The cartoon monsters and backgrounds, with their unusually dark colour palette, look excellent, whilst the evocative soundtrack is highly hummable; sound effects, too, are immaculate, particularly the anguished screams from eaten neighbors and evil laugh from the devil-dolls.

Another major part of the fun for the cinema-loving Jonathan Rosses of this world (I’m sure known SNES-fan Ross must surely have owned a copy?) lay in spotting all the specific horror-flick references littered throughout. Those are the giant mutant radioactive ants from Them!, that’s the gill-man from Creature From the Black Lagoon, those are the Graboid worm-things from Tremors, those bulbous, brain-headed green Martians come straight from This Island Earth, Invasion of the Saucer-Men and the old Mars Attacks! trading-card series.

The devil-dolls are surely Chucky from Child’s Play crossed with the other similar haunted mannequins from the Puppet Master series, Zeke and Julie’s cloned pod-people are themselves cloned directly from Invasion of the Body-Snatchers, while the ‘Titanic Toddler’ giant baby boss is what would have happened if Attack of the 50-Foot Woman had actually been called Attack of the 50-Foot Baby.

Castlevania players, meanwhile, might even spot the Count Dracula figure is really called Vlad Belmont, after the vampire-slaying clan in Konami’s classic platforming series – a neat nod to the game’s publisher. LucasArts lovers may also be delighted to find a secret level based on fellow in-house B-movie-themed point-and-click, Day of the Tentacle. Apparently, LucasArts actually had to gain legal clearance to include some of these enemies, so obviously were they based on other companies’ intellectual property: thankfully, parodies are largely exempt from usual copyright laws.

Neighbours from hell

Unfortunately, so great was the game that it sold well enough to gain a rushed, near-immediate sequel, 1994’s Ghoul Patrol, which was so rubbish it acted on the franchise much as a crucifix does on a vampire. Accounts differ as to how this came about. Some claim Ghoul Patrol was outsourced to a small Malaysian company named Motion Pixel, who didn’t do a good job on it. Another account has it that a separate internal team at LucasArts were originally developing it as an entirely separate generic shooter before bosses ordered it be hastily converted into a new outing for Zeke and Julie for easy money.

The format of Ghoul Patrol – rescue neighbours from monsters – was basically the same as Zeke and Julie’s earlier outing, but level design and controls were vastly inferior (what was the point of the new ‘jump’ button in a non-platformer?). Worst of all, the cartoon aesthetics were altered to a more ‘realistic’ design, with something of a 1980s Evil Dead-type vibe; you were now fighting evil demons from hell, not 1950s men-in-rubber-suit movie-monsters from a mad scientist’s lair. Today, you can now get both Zombies Ate My Neighbours and Ghoul Patrol as part of a two-in-one pack on virtual console services; my biggest criticism of it would be that it includes Ghoul Patrol.

Zombies Ate My Neighbors’ actual sequel emerged in 1997, when chief creators Mike Ebert and Dean Sharpe had left LucasArts and so no longer held the licence to their own brainchild. Therefore, they reused the basic overhead-shooter mechanics, sans the neighbour-rescuing element, within a new ancient Greek setting, in the now forgotten PlayStation and Saturn title Herc’s Adventures.

Despite reasonable reviews, the game sold fairly poorly, although one element retained some resonance. Every time you die, you end up banished back to Hades from which you must fight your way back out to begin your quest anew – just like in that other more recent (and much better) game of Greek mythology, Hades.

In 2007, an unofficial rip-off from another developer appeared on PC, Xbox360 and PS3, called Monster Madness: Battle for Suburbia, but was by all accounts every bit as poor as Ghoul Patrol had been, and as commercially unsuccessful. There seemed little real prospect of the Zombies series ever rising once more from the coffin they carried it off in, then – until, in 2011, news emerged that one of the original game’s childhood fans, filmmaker and screenwriter John Darko, intended to adapt it into a horror-comedy film.

Well, that would be good. Then LucasArts would surely resurrect the series for easy cash-in purposes once more – but hopefully done properly this time. Don’t hold your breath, though. Over a decade later, the film’s script still remains mired in development hell. Ironically enough, LucasArts’ 1993 classic has become one of gaming’s ultimate zombie franchises.