When Automata got going as a video games company 40 years ago, we loaded our code into a primitive duplicator from an audio cassette recorder, and we cranked it through a four-way deck at eight times normal speed. We could turn out three dozen copies of commercial computer games in an hour, complete with self-adhesive labels and fancy cassette sleeves. But the thing about an audio cassette is that it has two sides, and the thing about computer data is it only needs one side to record on. So I reckoned the thing to do with the blank side was record comedy sketches and give each title its own theme song, all stuffed with references and clues to the gameplay. This would be called transmedia sometime in the future, back then it was called idiocy.

When the British computer boom arrived in 1981, so did micro-clubs and micro-fairs, and I got to meet my games players in the flesh for the first time. They were a whole lot smaller than I’d expected! I discovered I was writing games for a bunch of kids. I had no desire to change my output, so there was only one course of action open to me, and that was to treat the little sods as equals. If they didn’t understand my adult themes, or pick up on my references or wordplays, then I reckoned it was better for them to float to the top of my pond, because I was certainly not prepared to meet them at the bottom. It was good to make them laugh, but it was equally good to make them think.

The rest of the British video games industry didn’t amount to very much.

By 1980, there were a handful of us in the land, and we could all fit into one scout hut and share a taxi home. That’s not a metaphor, that’s a memory. The following year there were still less than a hundred of us, but by the end of 1982 we numbered around 460 labels with 1200 titles competing for a slice of the market, and the traditional media were taking notice.

Drawn by artist Christopher Penfold, The PiMan was Automata’s mascot and regular multimedia star throughout its heyday.

As for Automata, our first proper commercial success in video gaming came in 1981, by accident. I was offered a bulk buy of poor-quality C30 audio cassettes. C30 meant that the recording time available was fifteen minutes a side, so I planned to get rid of this stockpile by filling them up with as many games and audio entertainments as possible and flogging them cheap. The result was a compilation tape called Can Of Worms, packing in eight games and eight comedy tracks for the grand sum of £3. We had no overheads or business sense, and we sold them mail-order direct, so our competitors simply couldn’t compete at that volume and that price. I guess today’s download market means the industry has come full circle.

Love and death

When the first software charts began to appear in the early computer magazines, we found ourselves among the bestsellers, which was nice, and soon we were headed for the top of the heap, which was very nice indeed. And so it was that the first big Automata hit was a rag-bag of puerile stuff, offering instant gratification to the non-discerning player with a few minutes to spare and three quid in their pocket. As a reward to my fans, I increased the price of the next compilation tape to a fiver. I called it Love And Death. For the third compilation, I distilled The Bible down to eight games of 1K memory each and heard the first industry rumblings to the effect that I was economically if not mentally insane.

An early Croucher compilation in all its audio cassette glory.

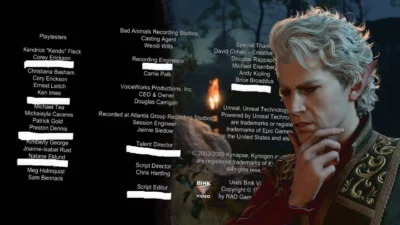

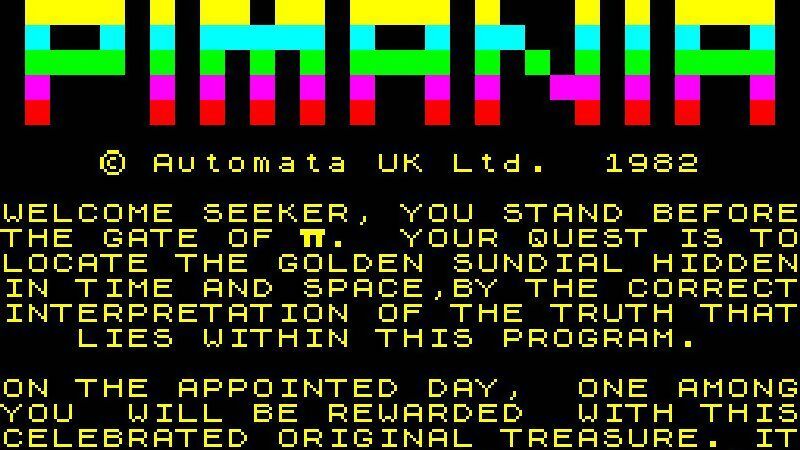

Pimania

But Automata was now a household name in the growing number of households that knew what video games were. Then, in April 1982, the Sinclair Spectrum was launched, and Automata was poised, ready, willing, and able to take a crack at making a little bit of gaming history. We had no experience of the video games industry, because the video games industry had just been born, and I was the midwife.

My favourite, and the most commercially successful title, was just like my very first radio broadcast computer treasure hunts from the 1970s, it was a head-on collision between the virtual world and the real world. This time round I hung it all on an anarchic cartoon character called The PiMan. And yes, he was raspberry-coloured. The whole thing revolved around exploiting this raspberry Pi in its various forms. Do I get my royalties now, guys?

Looking back, I don’t know if I invented multimedia gaming or not, but when I conjured up the computerised quest Pimania, I saw no reason to stay within the confines of the computer monitor. It was released in 1982 as a video game, a rock album, a comic strip, a t-shirt, a jumpsuit, a magazine, a social network, and a real-world treasure hunt for a gold and diamond prize, all of which needed the other elements for maximum participation.

A collection of Automata game music, The Piman’s Greatest Hits, emerged in 2017.

At one point, we had thousands of self-styled Pimaniacs searching for the prize in the real world, and I trickle-fed them clues via the game content, the weekly comic strips, and the music albums. The prize was eventually won in 1985, but commemorative cartoon books and Pimania albums are still selling, so I guess the little bastard has done OK for me.

The video games business that began in backrooms and bedrooms was now based in offices. The computer fairs had seriously outgrown the early venues and were now held in national exhibition arenas. In a way, the rot had already set in, and those vast expos were the death knell for most of the original games companies. They simply couldn’t afford to attend. By 1983 the video games business was going mainstream.

Enthusiasts and small companies like mine had done the spadework, laid the foundations, built the fabric and decorated the nursery, and then big business came sniffing around for an easy profit from our labours. Some small companies expanded too fast and overreached themselves, others were swallowed up by big players in media and entertainment. As for my little gang, we simply kept doing what we had always done, until I produced the game which nearly killed me. But that’s another story.

The best possible taste

While other tiny software companies and bedroom coders were knocking out clones of Asteroids and Space Invaders in the early eighties, Automata were busy exploring the stranger, more adult possibilities of their medium. Among the mini-games available on its 1981 compilation tape Can of Worms were such titles as Vasectomy, Smut, and Hitler; in the latter, you had to kill the now-elderly Nazi leader by sneaking a whoopie cushion under him, thus triggering a heart attack. It’s fair to say that, even at this early stage, Automata was crafting experiences you couldn’t find anywhere else.

You can read the other parts of Mel Croucher’s series here:

Part 1: Automata and the birth of the UK games industry

Part 2: How to grow a raspberry Pi

Part 3: How I made Deus Ex Machina