Something’s moving in the dark. You stalk forwards, slowly, trying to get a better look, but your senses aren’t quite working right. The shape in the distance remains motionless as you approach; all you can hear is an ominous scraping sound. Then, before you can run or let out a scream, the shape’s bearing down on you: a terrifying assault of teeth and shrieks.

The lights turn on. You switch off the console, and sit ashen-faced in front of the screen. It’s the end of the 1990s – and with the dawn of 3D, video games have become more terrifying than ever before. It’s the era of Resident Evil, Silent Hill, and countless other tense and horrifying games that have turned the medium into a war on the senses. Twenty years on, and those nineties kids who cowered in front of their televisions are now all grown-up – and some of them are making games.

Today’s generation of indies probably didn’t grow up on the 2D titans of the eighties. We’ve played the early Sonic and Super Mario games, sure, but for many of today’s creators, there’s a growing nostalgia for shimmering polygons, grainy textures, angular corridors, and the kind of thick fog you’d expect to see filling a laser-tag arena. The late nineties was a time when 3D graphics were on the march, but developers were only just getting to grips with ways of using them to terrify us.

“There are more people moving towards the low-res style, more people moving towards PlayStation and N64 nostalgia,” says Breogán Hackett, Irish indie developer and founder of the Haunted PS1 game jam community. “There’s a whole load of horror games being made, but very little community around it.”

Hackett has been running Haunted PS1 since March 2018, where it grew from a handful of hand-picked developers to a community of hundreds. Based on Discord and itch.io, Haunted PS1 regularly brings indie developers together for month-long jams to create low-poly horror games. Of course, much of this is down to accessibility: it’s much easier for solo creators to make the jump to 3D when textures don’t need 4K resolutions, and character models are counted in the dozens of polygons, not thousands.

But there’s more to it than that. Early 3D games were often experimental. The push against technological limitations of the time led to jerkiness and strange quirks that, whether they were intended to or not, combined to create a uniquely unsettling mood. No creator’s catalogue embodies this strangeness more than Kitty Horrorshow. For almost a decade now, the pseudonymous creator has built a library of short and sinister lo-fi experiences, funded largely by support on Patreon.

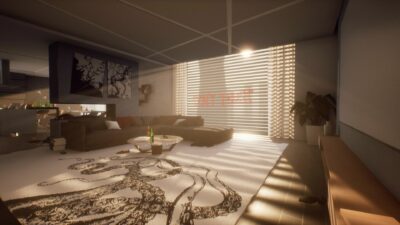

Favouring an atmosphere of growing dread over jump scares, Horrorshow’s games could be described as the gaming equivalent of found-footage movies, with their fuzzy imagery and gritty suspense. With Anatomy, released in 2016, Horrorshow builds a wholly terrifying experience that feels less like reliving a nineties game, and more like picking up a kid’s homemade video recording of one. While all of Horrorshow’s games use a striking, retro look to amplify their tension, Anatomy feels the most like a game out of time.

Anatomy: truly a game out of time.

Horrorshow isn’t alone, either. An increasing number of developers are using the nineties 3D look to make horror games. Hackett’s community began experimenting with it in jam projects like Broken Paradox, which kicked off its run of tiny horror titles. “Everything is a little less well-defined, so it’s hard to tell exactly what you’re looking at,” explains Hackett. “Especially PlayStation graphics, where there are jittery vertices and the textures are warping – it feels like the game can be falling apart at times. It’s really unsettling and unnerving.”

Embryonic states

That’s an opinion furthered by designer Jess Harvey. One of the three minds behind Arbitrary Metric’s 2018 fever dream Paratopic, she describes how the inherent “jankiness” and the industry’s embryonic state combined to create what she describes as “hauntological emotive connections for anyone that got to see a glimpse of things back then.”

Like Hackett and Horrorshow, Harvey also made her start creating smaller projects that explored where she could take the low-poly style. “I’d got a bunch of nineties-looking retro 3D jank experiments I’d been regularly revisiting,” she explains. “Nothing particularly spectacular, just exploratory work – what you can do with grime, how to drive things in an impressionist direction, experiments with composition, and so on. What Doc brought me felt like an opportunity to put into practice what I’d been itching to try out with this.”

That’s writer and game designer Doc Burford, who pitched the idea of an ‘anti-walking sim’ to Harvey in late 2017. Together with eventual IGF winner Chris I Brown, the three pitched Paratopic as an episodic series before focusing the project into a single release.

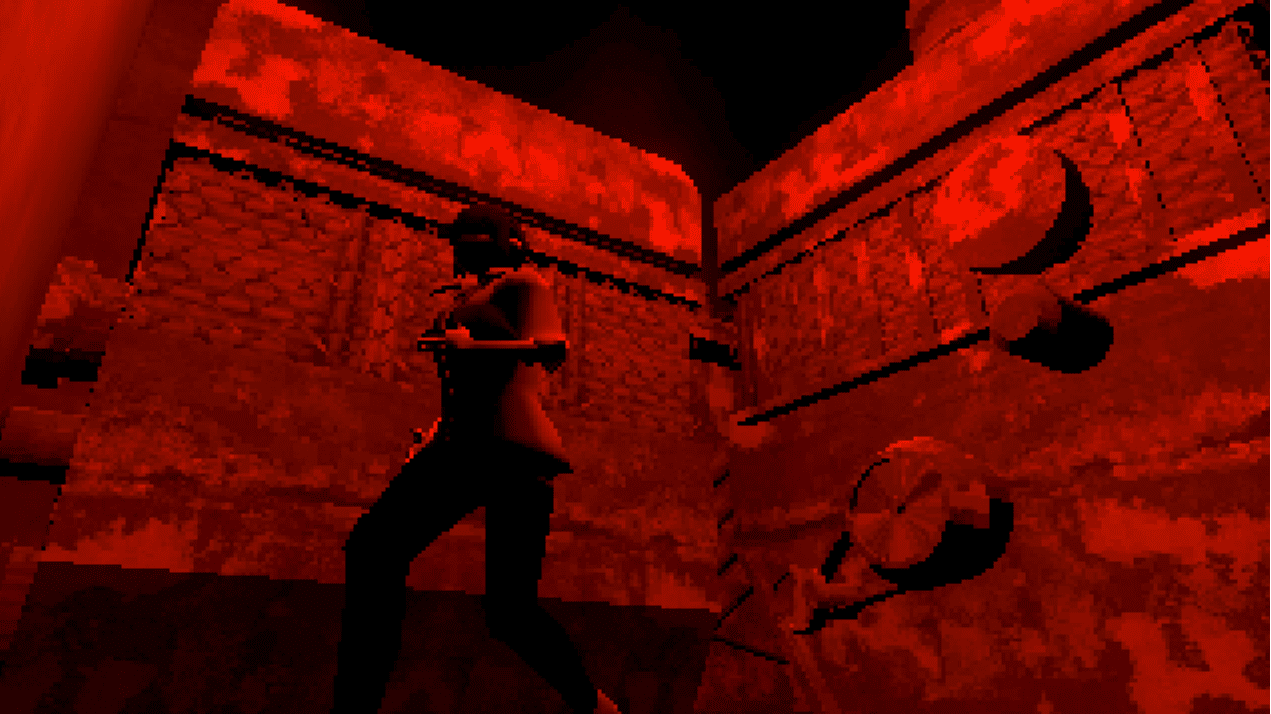

Something tells me this man isn’t your friend. It’s the highly unsettling Paratopic.

The pair pointed me towards Psygnosis’ PSone thriller Sentient’s freaky faces and the boundary-pushing visuals of The Terminator: Future Shock as key pieces of inspiration when making the game. But while Paratopic’s visuals might hark back to the PlayStation’s prime, its design is a straight reaction to more recent trends. Arbitrary Metric chose to use a retro aesthetic to frame a particularly sharp take on walking simulators – non-violent first-person games that forgo mechanics to focus on narrative.

“Ages ago,” says Burford, “I (told a friend) I didn’t enjoy walking sims, who challenged me to play some more. That got me thinking about why walking sims don’t appeal to me, and how I’d design a walking sim (that did).”

Filtering Paratopic through a retro 3D lens wasn’t just a personal preference, either. With unsettled lines and blurred textures, games of this kind feel as detached from time and space as the desolate locales that surround Burford and Harvey in the United States.

“From an outsider perspective, these parts of the States are existentially uncomfortable,” explains Harvey, who moved to the US five years ago. “Especially coming from the UK, a world where continuity gets taken for granted. People and events just flit through without leaving any kind of mark or permanence.”

Burford, who lives in Kansas, agrees. “Getting that sense of space, of going to a gas station at 3 am and talking to a guy who’s lonely and bored and desperate for company. Knowing a serial killer and understanding that the reason I came to know him was because he was scoping me and my family out.”

Meeting a murderer

In an interview with Into The Spine, Doc Burford elaborated further on his encounter with a serial killer, which took place around the year 2003. “There was this one time where animal control came to the house,” Burford told the website. “He told us that people had been calling because we were abusing our chickens. Of course, we weren’t, as he was quick to point out, but he had to stop by. He was friendly and outgoing, but he had to stop by every few weeks ‘cause someone was making calls. Dad and Mom liked him because he was a church-going Boy Scout leader. Seemed like a great guy.”

As it turned out, the visitor was Dennis Rader, better known as the BTK Killer, who’d murdered ten people in Kansas between 1974 and 1991 before his eventual arrest in 2005. “BTK had been telling people he had his sights on a new target,” Burford said. “I was told later that it was my family, which is why he’d been finding excuses to visit.” The incident would eventually inform several moments in Paratopic.

Point of view

You might have noticed a trend in the games mentioned so far. Almost without exception, Horrorshow, Hackett, Harvey, and Burford are largely working in the first-person horror mode popularised by more recent games like Amnesia and Outlast. First-person games weren’t unheard of in the PlayStation era, but the most seminal titles of the nineties were viewed from a third-person perspective: Resident Evil and Silent Hill pulled off their scares with a controlled approach to camera placement.

This summer’s industrial horror-themed Haunted PS1 jam is packed with games that go for a similarly remote viewpoint. Some, like redactionary’s Lynnwood, forgo Resident Evil-style pre-rendered backgrounds to simply follow the character through a real-time 3D world. The second of Bryce Bucher’s Two Atmospheric Atrocities takes a wholly opposite approach, with static backgrounds composed of grainy photographs taken in their own backyard.

Bucher’s Two Atmospheric Atrocities, uses grainy photographs as backdrops.

Elsewhere, Sleep Cycles, developed by creator kurethedead, explores Resident Evil-style puzzle-solving and storytelling mechanics while eschewing its fixed third-person cameras. It’s a Tomb Raider-style platforming adventure, but one where Lara Croft took a wrong turn into a realm of horror. Other games, meanwhile, pull the camera even further back, and replace slow-build scares with speed and gore. Modus Interactive’s Groaning Steel is a particularly gruesome racing game – it’s Carmageddon meets Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater as blood-and-bone-covered cars race through fleshy hellscapes.

Hackett explains that the diversity of creation in this field doesn’t stop at genre. Everyone has differing levels of ability, experience, and familiarity with the nineties aesthetic. Part of the appeal of making games in this style, after all, is the ease of creating textures, models, sounds, and stages without the stratospheric expectations of 2019’s mainstream games. “Some people (just add) a pixelation filter to whatever assets they have to hand,” says Hackett. “They’ll play with some of the modern technology but keep the feel of an older game through that and the gameplay. But I’ve also seen people go all-out with low-res textures, low-poly models. I’ve even gone as far as to fake lighting effects, so it feels less like a modern game with a pixelation filter over it.”

Hackett’s first retro horror game was the dark and moody Broken Paradox.

While the growth of the games industry could be described as a constant race for the highest frame rate, the sharpest resolution, or the fanciest lighting, Harvey likens the use of late-nineties design techniques to a filmmaker leaning on the established principles of cinema. “If this was a film, you’d most likely choose a grainy film stock,” Harvey says of making a typical Haunted PS1 game. “Perhaps (it could be in) black and white.”

It’s easy to see attempts to reimagine the past as simple nostalgia, but in essence, what these developers are really doing is tapping into a rich library of audiovisual tones. Growing communities like Haunted PS1 are building on foundations laid 20 years ago; developers like Arbitrary Metric are using familiar visuals to drive new and unsettling experiences.

Who knows what the next decade will bring? We’ve already seen classic twists on modern horror, and dark homages to PlayStation classics. As the medium matures, we’re sure to see developers continue to mine the past in order to terrorise gamers in the present. Until then, I’m happy to sit in the dark and wait for the next monster.