What began as a casual experiment has grown into an obsession. It all began when I purchased a Sega Game Gear – a battered relic from the early nineties that, like so many others, had long since stopped working. But doing a bit of research online revealed that it’s actually quite simple to resurrect a Game Gear by changing its capacitors – and so, despite not having touched a soldering iron for years, I ordered the components and set about trying to get the tired old console working again. Flushed with success, I fixed another Game Gear. Then I discovered that it’s possible to buy replacement screens – modern LCD screens that offer a substantial upgrade over the existing one – so I installed one of those. Before I knew it, my desk was covered in newly purchased equipment – a soldering iron, a hot air rework station, and, most recently, a budget oscilloscope – and I’d embarked on a whole new hobby.

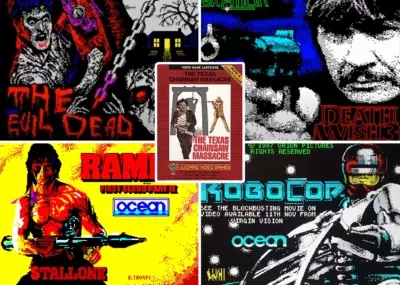

Straight from Mathijs Nilwik’s garage in the Netherlands: a Game Gear main board. Perfect for bringing a dead system back to life.

It turns out I’m far from alone in all this: from Facebook groups to Discord channels, there’s a lively and thriving community around the handheld refurbishing scene. Take Andrew Hendrick, for example: he too had fond childhood memories of the Sega Game Gear, and so, with the UK in lockdown due to the pandemic, he brought one to play around with in his spare time. Once again, the Game Gear was broken – because the leaky capacitors Sega used in these handhelds mean they all break eventually – but Hendrick decided to see if he could fix it. “In November [2020], I just decided to buy myself one,” he says. “I recapped it, and it worked. Then I did some research, and found the [replacement] screen. I had no soldering skills whatsoever, but I really enjoyed it. So I thought, ‘What else can I do with it?’ So I decided to paint one.”

Thus began an entire new pastime – and growing side business – for Hendrick. He began painting Game Gear shells with an airbrush and selling them on eBay, and then in March 2021 set up his own website, Retro Gear Customs, where he could sell refurbished, customised Game Gears. Meanwhile, he was practising and refining his approach to painting his shells: “Rather than painting the outside, I painted the inside of the shell. Everything I do is handmade – it’s not printed. I started painting them in lockdown and that’s how it [all began].”

GHOST IN THE SHELL

Hendrick is but one of a growing number of hobbyists and professionals who’ve begun making replacement shells and other parts for handhelds over the past few years. Although founded in 2013, British company RetroSix has really seen its sales explode since 2020, with its online shop offering repairs and a wealth of mods and replacement parts for everything from the original Game Boy to current-gen home consoles.

If you have a worn-out Game Boy lying around, it’s relatively simple to refresh it with a new screen, shell, and buttons.

RetroSix’s first product was a replacement shell for the Game Boy Advance – a business decision that, according to founder LukeMalpass, was partly born out of frustration. “I started it because the quality of the actual plastic was terrible,” he tells us of the existing shells he found on the market. “It was the only thing available – these cheap Chinese shells that don’t fit very well. So I made the 3D models, the moulds, the injection moulding, perfected it all, and released it. And that’s what I got known for – high-quality moulds.”

Today, it’s possible to take a tired, broken old handheld console and give it a new lease of life. You can replace the shells and buttons, improve the audio with better speakers and sound-boards; even replace the Game Boy and early Game Boy Advance’s dim, un-backlit screens with pin-sharp, modern ones. Thanks to the handheld modding community, you’ll also find replacement parts for more obscure systems like the Atari Lynx or Neo Geo Pocket, and even replacement LCD screens for the PlayStation Portable.

One hobbyist who’s really pushed the modding boundaries, though, is Mathijs Nilwik from the Netherlands. An engineer by trade, he began his console repair pastime around four years ago. “I’ve been repairing Game Gears for years – swapping capacitors, mainly, and later, replacing screens. I was just buying and selling them.”

Gradually, though, Nilwik noticed just how many Game Gears he was encountering that were completely destroyed, either because of leaky capacitors or battery acid eating into the systems’ boards. His curiosity piqued, Nilwik began to see if he could reverse-engineer a replacement motherboard, while at the same time refining it to reduce the number of components. “I have experience in redrawing boards, so it took a few days to reproduce the original board and fill in all the details,” he says. “Then removing the components took time, because I needed to understand what I could remove and what I couldn’t.”

Making a replacement motherboard meant that Nilwik could take an otherwise broken Game Gear and breathe life back into it: as long as the main CPU, brightness wheel, and cartridge connector were in working condition, he could install those on his new board and get the handheld working again. And thanks to the wealth of replacement parts now available, it’s possible to build a Game Gear that is almost entirely new – at the time of writing, RetroSix is on the cusp of putting new replacement cartridge connectors on sale, so all that’s needed is that original ASIC chip from a donor Game Gear. (A later revision of Nilwik’s board allowed the use of a modern brightness wheel, since the originals are no longer in production.)

The wealth of replacement shells available means you can create a very different-looking console from the ones that rolled off the production line all those years ago.

Nilwik first unveiled the SYF board in late 2021, and the sheer level of interest caught him by surprise. “I didn’t expect the demand for it,” he tells us. “I expected [to get orders for] maybe 50 boards, but then I saw the amount of attention it got; that was a challenge. I either needed to outsource my assembly or do my own.”

After ruling out the possibility of getting his boards produced in China, Nilwik made a surprising decision: he’d simply assemble them himself, in his own garage. “I have a pick and place machine – I brought a used one from a company here in the Netherlands that makes hi-fi amplifiers. I saw it up for sale and I told my wife, ‘I want to get this and give it a try.’”

Before long, Nilwik had all the equipment he needed to generate the boards and install its array of surface-mount components. “That was also a learning curve for me,” Nilwik says. “I knew those machines existed, but I had to figure out how it worked. It was a Chinese machine, so I had to translate the interface into English.”

Creating products like these is something of a leap of faith, since installing a miniature assembly plant in your garage requires a fairly substantial financial outlay (“It takes a lot of money to start – it’s not a few hundred euros,” says Nilwik). And when you’re dealing with something relatively niche like the Sega Game Gear, you’re taking a potentially big risk, as Malpass points out. “Nobody’s stupid enough to spend the amount of money I did on something that takes a long time to sell,” he says. “We needed a warehouse’s worth of space to store a small production – you have to make 1000 shells, minimum. So we ended up with 16,000 Game Gear shells [in] different colours… we’ve made the money back now since we were successful with it, but it’s hard to get right.”

There are all kinds of drop-in mods for the Game Boy Advance, making it one of the friendlier handhelds to upgrade.

There’s a reason why people like Malpass, Nilwik, and Hendrick are so into modding consoles, though: there’s something satisfying about taking something tired or broken and making it feel like new. You could call it a video gaming twist on the so-called ‘IKEA effect’: the notion that we all have a greater connection to something we’ve made or repaired ourselves. “People get the experience and pleasure of putting them together for themselves,” says Malpass. “They’ve put things together and it’s started working… it’s like LEGO, isn’t it? You feel like you’ve accomplished something, even though all you’ve done is followed a bunch of steps. You enjoy it more than if someone bought you a [pre-built] LEGO statue.”

“Bringing something back to life from the 1990s is so satisfying,” Hendrick concurs. “It’s therapeutic as well.”

This might even explain the dedicated online community that’s clustered around the Sega Game Gear in recent years. A less solidly built machine than its contemporary, the Game Boy, the Game Gear’s fragility helps endear it to a group of enthusiasts who enjoy nursing the consoles back to health. “There’s something about Game Gears,” Hendrick says. “With Nintendo, they just work.”

“Nintendo products don’t break,” adds Nilwik. “You can clean them a bit, and they work. But Game Gears are always broken, so it’s always a bit of a challenge to repair them.”

Andrew Hendrick sells restored Game Gears, rehoused in hand-painted custom shells.

RISING PRICES

With a growing market for all things retro, however, comes rising prices. For years, old handhelds were readily available from online auctions and car boot sales for just a few pounds; today, even a tired, broken system can easily sell for £30 or more. “Two years ago, when I started, I could go to a retro event and pay £4 for a Game Gear,” Malpass says. “Some people would even just give them to me, saying, ‘These don’t work’. Now, it’s £40 or £50 just for a broken one. But still, I like to think I’ve helped grow the scene again.”

“When I started, I was buying Game Gears off eBay for £20–25 each,” agrees Hendrick. “Now I’m struggling to find them below £35–40 – they’ve gone up a lot.”

At one stage, Malpass says he was able to buy as many as 40 broken Game Boys from eBay and have them delivered the next day; today, he’s finding it much harder to readily source units that he can refurbish and resell. “That means we put our prices up. I started selling them at £65 two years ago; then they went up to £130 a year ago. Now we’re selling them at close to £300. We sell five consoles a day, seven days a week, so people are willing to pay for quality. But as the consoles get rarer, the prices have to go up.”

Assuming you can stomach the rising costs of those old consoles, though, the cost of upgrading them isn’t necessarily exorbitant if you’re willing to do the mods yourself; even once-expensive modifications like replacement screens are cheaper and easier to install than they were a couple of years ago.

You’ll find a number of screen mods for the Game Gear, made by the likes of McWill, BennVenn, RetroKAI, and RetroSix. All are far superior to the original, blurry panel.

As a starting point, Malpass and Hendrick agree that the original Game Boy or Game Boy Advance are ideal for newcomers. “I’d start with the Game Boy Advance, because you can literally fit a screen with no soldering,” says Malpass. “You just place it in, connect the ribbon, and then you can replace the buttons and shell without too much work. It’s definitely the easiest of the consoles, I’d say.”

“I’d say, don’t try and mod a Game Gear straight away,” adds Hendrick. “Do something slightly easier… you really want to start on a Nintendo [Game Boy Advance] because there’s usually little to no soldering on those – the modifications have been built that way.”

Beware, though: as I’ve already discovered, reviving these ageing, much-loved systems can be addictive. “Oh yeah, we rarely get a person buying one thing,” Malpass says. “They’ll come back for more and more. They’ll build themselves an orange [handheld], but then they need an excuse to build another one – until they have a room full of them…”