First unveiled in November 1988, the SNES prototype was very different from the one that launched in 1990.

In the US and Japan, in particular, the Nintendo Entertainment System dominated console gaming through the second half of the 1980s. Selling around 14 million units worldwide by the end of that decade, the system’s success led to increasing speculation over its successor as the nineties approached. Nintendo’s rivals certainly didn’t drag their feet when it came to making their own, more powerful consoles. NEC launched the PC Engine in 1987 which, with its 16-bit graphics, futuristic form factor and extensible design (allowing for add-ons like a CD-ROM drive), made the four-year-old NES look somewhat dated.

In 1988, Sega launched the Mega Drive (or Genesis in the US) – the 16-bit, curvaceous successor to its Master System. Nintendo, on the other hand, refused to be rushed. The company first publicly confirmed that it was working on a new console in September 1987, but didn’t formally show off what it had planned until the following year; from there, the originally-intended 1989 launch date slipped to 1990.

There was a good reason for Nintendo’s slow-and-steady build-up to the launch of the Super NES – its 8-bit predecessor was such an ongoing success, there was no need to rush into making a new system. The NES may have looked a bit antiquated when compared to its late-eighties competition, but with a library of games numbering in the hundreds, and the smash success of Super Mario Bros. 3 taking the console into the early 1990s, its technical inferiority hardly mattered. Indeed, the challenge of transitioning its users away from the NES and onto the SNES was clearly high on Nintendo’s agenda in the late eighties.

A prototype Super Famicom sitting next to the ‘Famicom Adapter’. Image credit: Chris M Covell.

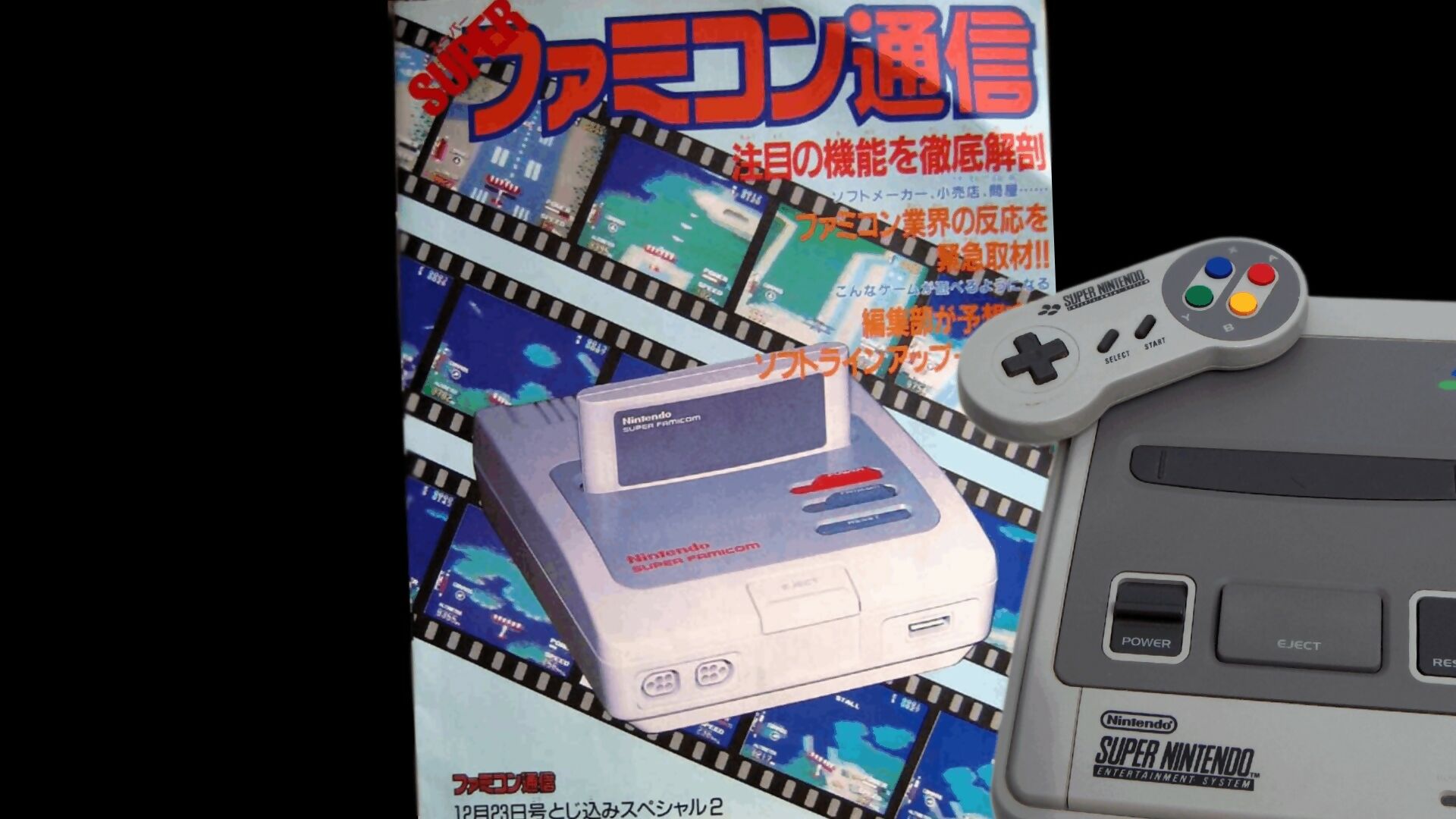

When the SNES was first formally shown off to Japanese journalists on 21 November 1988, it was displayed alongside something Nintendo dubbed the “Famicom Adaptor” (Famicom, short for ‘Family Computer’, being the Japanese name for the NES). Japanese magazine Famicom Tsushin Magazine carried one of the first reports from this unveiling, with copious photographs of the prototype SNES and its ‘adapter’, as captured by Chris M. Covell on his website.

Backwards compatibility was something on rival manufacturers’ minds at this point. Sega allowed its users to play Master System games on the Mega Drive via a device called a Power Converter. Throughout its various iterations across its seven-year lifespan, the PC Engine remained compatible with both its CD and card-based media. For a while, it was clear that Nintendo intended to follow suit. In an edition of Computer & Video Games magazine, published in February 1989, British gamers got what may have been their first look at the Super Nintendo. Although some of the styling cues are familiar, the prototype also looked strikingly different, with an unusual arrangement of three buttons on the top, a headphone jack on the side (something later dropped) and red buttons on the joypad.

Nintendo’s SNES prototype, as unveiled in November 1988 and published in C&VG magazine. They in turn reprinted the image from Japanese outlet, Famitsu.

“It’s a very attractive-looking machine,” the magazine wrote, “and is fully compatible with all existing Nintendo titles – thus giving the machine an instant library of some 400 titles!” So was the SNES ever truly backwards compatible with the NES? The short answer: sort of, but not really.

What Nintendo introduced to the press as a Famicom Adapter was, in essence, a revised NES with an AV-out port on the back. Users would have connected this to their SNES and slid the middle switch on the top of the latter system, thus allowing the signal from the NES to pass through the SNES and up to their television – the idea being that users could play their back-catalogue of games while benefiting from the SNES’s superior RGB image quality. The original Japanese NES (or Famicom) output its signal via fuzzy RF, so Nintendo were looking into a scheme where customers could trade-in their old systems for a shiny new SNES and an optional Famicom Adapter to go alongside it.

The photograph of the SNES prototype, originally sourced from Famitsu magazine, doesn’t show the Famicom Adapter, but it’s just possible to make out the three buttons on the top of the SNES’s case – the middle button was marked ‘Famicom’, which is potentially where the slightly garbled news that it was “fully compatible with all existing Nintendo titles” first emerged. There are clues still buried inside the SNES, however, which indicate that true backwards compatibility really was explored at Nintendo. As hardware expert Foone pointed out on Twitter in 2019, “SNES carts actually start up in 8-bit mode. They then have to tell the CPU to switch into 16-bit mode… It starts up in 8-bit mode because that’s the mode it has to be in to run NES code.”

fun fact about that: Much like how PCs (up until EFI, maybe?) boot in 16-bit mode and have to have a bootloader that switches to 32bit/64bit mode, all SNES carts actually start up in 8-bit mode.

They then have to tell the CPU to switch into 16-bit mode.— foone🏳️⚧️ (@Foone) March 16, 2019

Couple this with the SNES and NES sharing the same protocol, and you have a fair bit of evidence that Nintendo had looked into making NES games somehow playable on a SNES at some early stage in its life. What is clear, though, is that the Famicom Adapter was quietly dropped altogether between the SNES’s first public demo in November 1988 and its second showcase in July 1989. In its revised form, markedly closer to the production version released in 1990, the Famicom slider switch is conspicuously absent from the SNES’s case.

We got in touch with Julian Rignall, who was deputy editor of C&VG in 1989, to ask if he remembered those pre-release days of the SNES. “Nintendo’s plan was to have backwards compatibility with the NES,” he told us, “but the feature was cut, I assume to save money as this would have added a fair bit of cost to the machine.”

Released on 21 November 1990 – two years to the day after its first public unveiling – the SNES therefore represented a clean break from the 8-bit generation. But with Japanese gamers flocking in their hundreds of thousands to get their hands on a shiny new console and a copy of its biggest launch title, Super Mario World, it’s likely that backwards compatibility was far from the front of their minds.