Tár and The Matrix Resurrections are recent examples of how, in cinema, video games are often depicted as a lowbrow form of art.

NB: The following contains spoilers for Tár, if you’re concerned about that sort of thing.

The ending of the Oscar-nominated 2022 drama Tár sees our protagonist, acclaimed conductor Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett), preparing for a new concert in the Philippines. We see her diligently carry out the same tasks she performed earlier in the film (before her abuses of power caught up with her) while the maestro of the Berlin Philharmonic: she studies the score, she rehearses with the musicians, she surveys the performance hall.

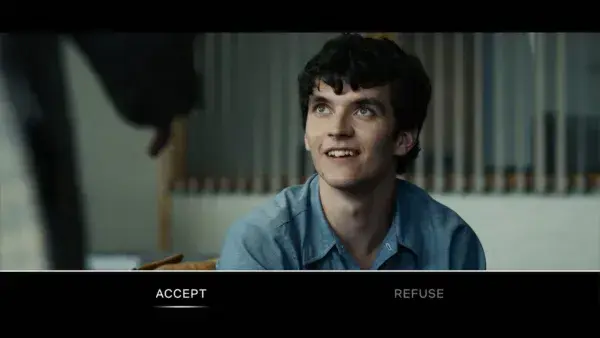

We cut to moments before the concert itself. The lights go down, CGI imagery is projected behind the orchestra, and the players begin. We cut to our audience, an enraptured crowd of young people in Monster Hunter costumes. And this is the film’s final image: Lydia Tár, once the doyen of classical music, now conducting video game music to a hall of cosplayers.

Some view the final stretches of the film as cryptic and open to interpretation, but there is one thing that critics could easily agree on. This final scene is a “cinematic punchline”, “a pointed satire”, for Lydia – “almost a fate worse than death”. Reviewers were keen to emphasise Lydia’s ‘reduction’ in this moment, her “huge fall from grace”.

The cultural value judgement at play is clear: for a musician as accomplished as Lydia Tár, to be conducting video game music is the ultimate humiliation and punishment.

Cate Blanchett in 2022’s Tár. Credit: Focus Features/Universal Pictures.

In interviews, however, the film’s director Todd Field has distanced himself from the view that there is something inherently demeaning in Tár’s Monster Hunter concert. He goes so far as to draw a parallel between the contemporary perception of video game music as lowbrow and (as argued by John Mauceri in his book The War on Music) the ‘ghettoisation’ of great twentieth century composers like Max Steiner, whose work in film scores rather than the prestigious musical halls of Europe was down to antisemitism, not demerit.

“No serious [modern composer] will tell you”, Field told the Script Apart podcast, “that they’re not composing for video games, because that’s the largest audience”.

Indeed, nowadays, orchestral performances of games music in prestigious music halls are a common occurrence. Aerith’s theme from Final Fantasy VII is played not infrequently on Classic FM. Last year, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra performed an entire concert of games music at the BBC Proms. Still, to critics at large, the depiction of an accomplished artist performing games music on film can only be seen as preposterous. But when we consider the depiction of gaming culture on film in general over since its inception, perhaps it was inevitable that Tár’s ending could only be misconstrued.

In the early 1980s, some of the earliest films to prominently feature video games treat the fledgling industry with suspicion, not to mention a pinch of Cold War paranoia. In The Last Starfighter (1984), the hero discovers the arcade game he’s hooked on is a recruiting tool for a real intergalactic conflict, while in WarGames (1983), a young hacker attempting to pirate unreleased games runs afoul of a rogue supercomputer programmed to wage nuclear war against the Soviets.

Both films speak to a cultural anxiety towards a new form of entertainment; the worry that this seemingly innocuous pastime is giving youngsters nefarious skills that could be dangerously misused. Two decades later, anti-games campaigners like Jack Thompson had successfully embedded the popular notion that video games only had the capacity for violence and corruption, an idea exploited by the likes of 2009’s Gamer, starring Gerard Butler, which sees sadistic FPS players taking control of prisoners and forcing them into a real-life Death Match.

This idea of becoming a real life avatar within a video game is also a common trope when attempting to incorporate games culture into films, as seen in movies like Tron (1982) or Free Guy (2021). The latter casts Ryan Reynolds as a hapless NPC in a Grand Theft Auto-style experience. The most recent high-profile example of this type is Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018), an adaptation of Ernest Cline’s novel, set in a dystopian world where a dejected populace take solace in ‘The Oasis’, a huge virtual reality game.

Free Guy, starring Ryan Reynolds and Jodie Comer. Credit: 20th Century Studios.

Ostensibly a film about gaming, Ready Player One has a strange texture; it has all the bells and whistles you’d expect from a Spielbergian extravaganza but its engagement with its gaming element seems perfunctory, and it’s hard to see what pleasure the players are deriving from The Oasis – a drab, joylessly IP-stuffed virtual smorgasbord. Spielberg’s influence secured the film rights to feature hundreds of media references, but tellingly, the film’s major pastiches are all from movies (particularly The Shining). It’s almost as if, for Spielberg, there was no gaming cultural totem for him to hang onto.

If films have struggled to engage meaningfully with the cultural impact of video games, they have at least been unable to ignore the seismic business that the industry creates. In eXistenZ (1999), Jennifer Jason Leigh plays Allegra, a famous game designer who finds her life under threat from a cell of assassins called the ‘Realists’. In Cronenbergian fashion, gamers must undergo surgical enhancements so they can ‘plug in’ to their game pods via fleshly umbilical cords, the energy of their own body’s serving as the game’s power source. This fusion between the virtual game world and the player’s real body foregrounds the anxiety experienced by Jude Law’s character, Ted, as he and Allegra delve further into the game and he begins to lose his grip on reality.

Cronenberg was inspired to make a film about a game designer facing death threats after discussing whether games could be art in an interview with Salman Rushdie in the mid-90s, and though he sadly displayed great prescience in predicting the levels of abuse that would be levelled at developers, the film is primarily interested in using games as a metaphor for the lack of control we humans exercise over our everyday lives. “We’re stumbling around in this unformed world whose rules and objectives are largely unknown,” despairs Ted partway through the film.

“But it’s a game that everyone’s already playing,” Allegra reminds him. There is no joy to be extracted from video games in this world; they can only be an extension of existing anxieties.

In Paul Verhoeven’s Elle (2016), Isabelle Huppert plays Michèle, the CEO of a games company currently developing its second title. The scenes set in Michèle’s games studio can seem laughably bad: the developer brief is nonsensical, the game’s graphics are dreadful, and a cutscene where a woman is violently impaled by a snake is grotesque to the point of parody. But given Verhoeven’s satirical pedigree, I don’t think he intends us to take it seriously.

Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, starring Isabelle Huppert. Credit: SBS Productions.

At the beginning of the film, Michèle is violently assaulted in her home by an unknown assailant, but more shocking still is the placidity of her response, and her later developing of a quasi-sadomasochistic relationship with her own rapist. Needless to say Elle is a frequently troubling film, but it has a sheen of dark humour, and for Verhoeven the gaming aspect is a satirical vehicle; in particular the cavalierness of the studio regarding the game’s sexual violence (“Kwan”, chides Michèle, “we agreed the orgasmic convulsions are way too timid”) is in service to our heroine’s complicated response to her assault.

It speaks to the relative failure of films to meaningfully engage with gaming culture that, over two decades on, The Matrix (1999) surely remains the definitive cultural fulcrum for the intersection between films and games. The Wachowskis’ multi-media ambition made gaming inherent to the fabric of the series (Jada Pinkett Smith who plays Niobe in the second and third movies was frequently unsure on-set whether she was filming something for the movies or the action-adventure spin-off, Enter the Matrix). The filmmaking duo even delegated the canonical death of Morpheus to the long-departed MMORPG, The Matrix Online.

The Matrix isn’t about video games per se, but Neo and Trinity frequently feel and behave like video game avatars, dropping ammo like disposable candy to the tune of that bullet time slickness that would become ubiquitous in games of the early 2000s. This undoubtedly contains the violent power fantasy derided in films like Gamer, but the Wachowskis understand that the appeal of games goes beyond the base.

Fundamentally, The Matrix is about transcending your ordinary existence, feeling power that does not exist in your corporeal body, of attaining agency in a life you do not feel control over. The subsequent coming out of the Wachowskis as Trans women has also shone greater light over the metaphor inherent in the Matrix’s “residual self-image” which allows the cohesion of one’s inner and digital selves; an especially poignant one given how video games can frequently function as a safe space for LGBTQ players to explore their sexuality or gender identity.

Read more: Enter the Matrix: exploring a unique tie-in game at 20

Twenty years after the original trilogy, 2021’s The Matrix Resurrections brought the gaming aspect of the series to the forefront, recasting Neo/Thomas Anderson as a veteran game designer, and the events of the original trilogy as those of lauded games he created. Of course, this world is an illusion; it’s the work of the Analyst (Neil Patrick Harris), a program suppressing Neo’s memories of the real world. Despite this plot device, the film doesn’t overtly punch down at the games industry, and its depiction of Neo’s game studio at work is certainly less cringe-inducing than what we see in Elle (rather strangely but probably wisely, when showing Neo’s game it simply reuses footage from the original movies).

The Matrix Resurrections. Credit: Warner Bros. Pictures.

It’s no accident, however, that the Analyst has chosen to disguise the truth of the Matrix in the form of a game. As new character Bugs (Jessica Henwick) tells Neo, “They took your story, something that meant so much to people like me, and turned it into something trivial… Where better to bury truth than inside something as ordinary as a video game?” For the Analyst, it’s the very triviality of video games that makes them the perfect hiding place for profundity.

In general then, there’s an uneasy history of video games and gaming culture’s representation on the big screen. If filmmakers aren’t overtly hostile or uninterested, they tend to use games in service to something else they want to explore rather than as a worthy subject of its own. Even a series which holds games as close to its heart as The Matrix cannot help but mark the ostensible lowbrowness of the form, and the limitations imposed by gaming’s cultural ghettoisation.

Personally, I don’t think this dissonance between the cultural influence of the games industry and its limited articulation in cinema is sustainable. Perhaps a newer crop of directors like Jordan Peele, (who in conversation with his pal Kojima expressed interest in making a game himself) can discover a better way forward for games on film. Maybe then we’ll be in a place where a scene such as the ending of Tár is allowed to be read in good faith.