Almost five years later, Netflix hasn’t yet attempted to repeat the ambition of the Black Mirror interactive episode, Bandersnatch.

Once a games journalist himself, Black Mirror writer Charlie Brooker revisited the formative gaming years of his youth in the 2018 episode, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.

About a teenage British programmer attempting to turn a Fighting Fantasy-like game book into a video game, it captures a seminal moment in British tech history. By 1984, affordable computers such as the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64 had turned a generation of kids into amateur (and in many cases, professional) game developers. What began as a cottage industry in the late 1970s had bloomed by the mid 1980s, with software houses like Ocean and Codemasters packaging and marketing dozens of titles per year – and making millions of pounds in the process.

Bandersnatch is steeped in that history, with the episode taking clear inspiration from Imagine Software, a game developer founded in 1982 before going spectacularly bust two years later. Its collapse was famously captured by a documentary crew and aired on the BBC as part of the series, Commercial Breaks. Brooker evidently saw that documentary, because his story’s fictional studio, Tuckersoft, is evidently based on Imagine, right down to the lighting and layout of its offices.

The name of the episode itself is taken from an ambitious title Imagine’s programmers were working on when the company went bust – a so-called ‘mega game’, Bandersnatch was heavily promoted with full-page adverts in British magazines of the day. Thanks to Imagine’s terminal cash flow problems – that is, the company appeared to be spending the cash faster than it could flow in – the game was never completed.

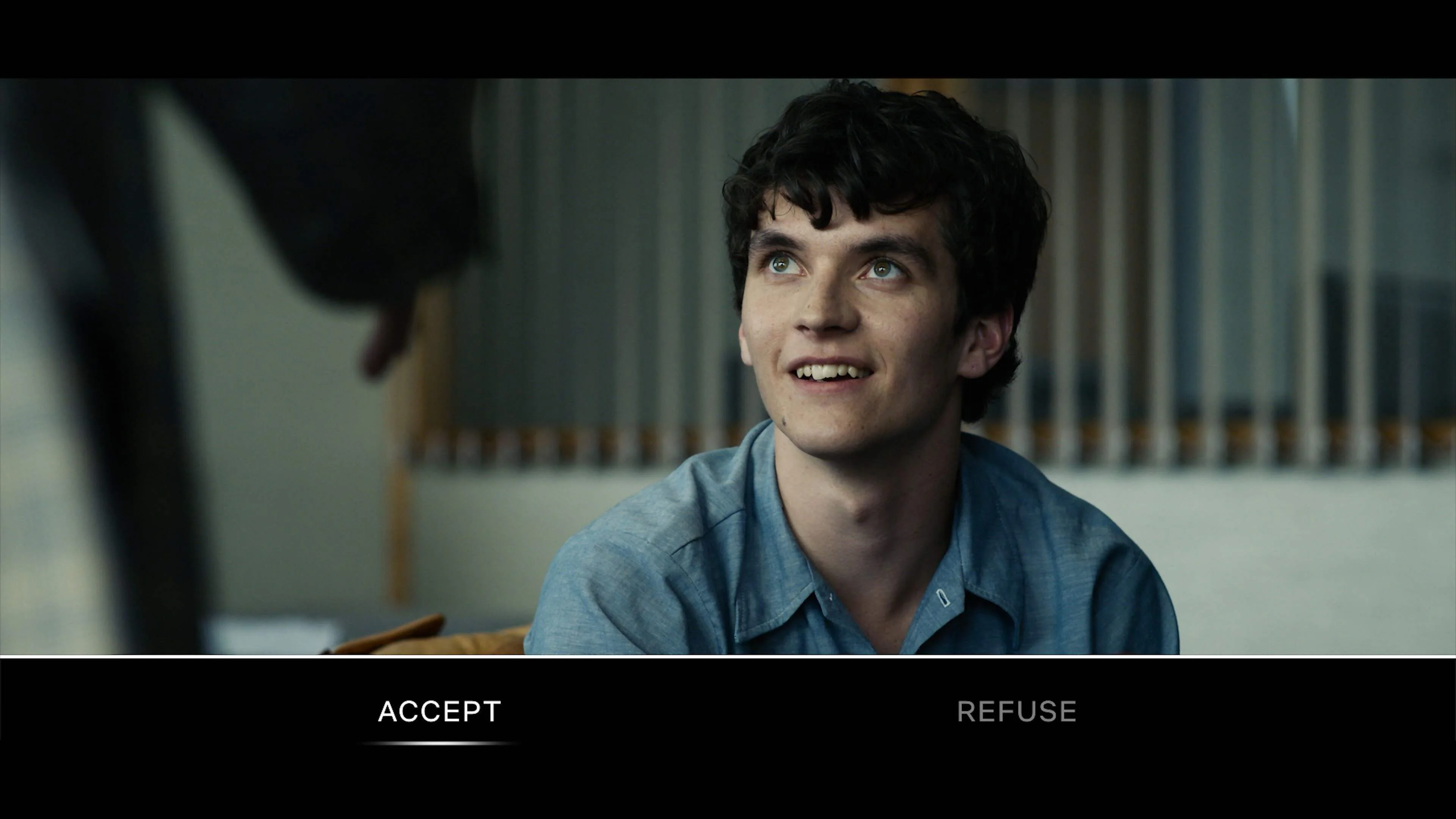

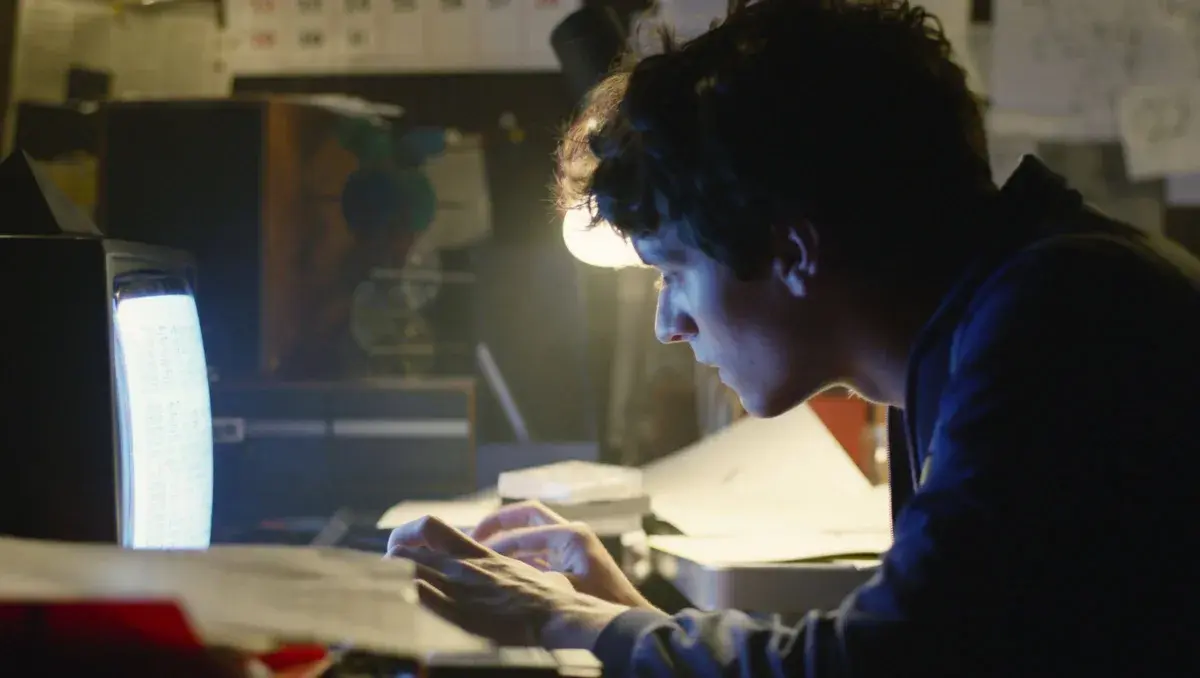

Beyond nostalgia for the redundant tech and defunct studios of the 1980s, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch is memorable for another reason. The episode, much like the game protagonist Stefan (Fionn Whitehead) is working on, is a work of interactive fiction. At certain points in the episode’s plot, the action pauses, providing the viewer a few seconds to select a choice using their remote control.

In some instances, these choices are largely meaningless; picking between breakfast cereals or what music Stefan should play on his Walkman, for example, does nothing to obviously further the plot. Other choices, meanwhile, cause the plot to branch off wildly, resulting in shock character deaths, several dead ends, and eventually, one of five or more endings (in interviews, Brooker said even he’d forgotten exactly how many endings Bandersnatch has).

According to a 2018 Wired article, Black Mirror’s interactive fiction concept came from Netflix’s producers, and not Brooker; indeed, he and his producer-partner Annabel Jones were initially doubtful about the idea. “Afterwards I was like, ‘Those things never really work,’” Brooker recalls saying to Jones following a meeting at Netflix. “We couldn’t see what the story would be.”

Brooker and Jones later changed their minds when they came up with the germ of Bandersnatch’s plot – a developer trying to make a choose-your-own-path game, and then becoming convinced he’s trapped in one himself. It was a concept perfect for Netflix’s interactive TV game pitch.

Credit: Netflix.

At the time, Netflix was seemingly intent on seeing just how far it could push these interactive stories. It had already made Puss in Book: Trapped in an Epic Tale, and wanted to see what else could be done with a mixture of streaming and simple inputs from the viewer.

This ambition explains why Netflix was happy to spend what was likely a considerable amount of money on Bandersnatch’s production; although the episode could theoretically be completed in 40 minutes or so, the finished experience would have numerous different endings and multiple alternate scenes, which would all have to be shot, edited into clips, and then connected together in an in-house piece of software called Branch Manager.

The writing process was hardly less complex for Brooker, who took to using the interactive fiction engine Twine in order to help write the fragmented, densely-woven script. You can get an idea of the script’s complexity by looking at this map on IGN, which lays out all the story’s branches and endings. By the standards of a typical interactive fiction video game, it isn’t necessarily mind-boggling; but once you consider that every node on the chart is a scene that had to be acted, shot, edited, graded – and in some cases, overlaid with visual effects – the scale of the production becomes clearer.

That complexity might explain why, to date, Netflix hasn’t attempted something quite as sprawling (or darkly adult) again. A typical viewer might have seen 40 to 90 minutes’ worth of footage; the amount of footage the episode contains as a whole reportedly amounts to more than five hours. There’s no reliable source that tells us exactly how much Netflix spent on Bandersnatch, but with all but the most dedicated viewer only seeing a small percentage of its content, the episode’s time and expense may have proven difficult to justify – particularly given that work on Bandersnatch took so long, it ended up delaying the airing of Black Mirror’s fifth season.

Credit: Netflix.

“We knew going into [Bandersnatch] that it would be difficult and challenging and more complicated than a normal film that we would do. Even then, we underestimated,” Brooker told The Hollywood Reporter in early 2019. “As the story expanded, I like to say that the story got longer and it got wider. So the whole thing started expanding a bit like an inflatable life raft in a small room.”

Almost five years on, Black Mirror: Bandersnatch remains a singular, fascinating experiment, with its interactive element does much to underline its central character’s growing paranoia. Its fourth-wall breaking moments, when Stefan begins to suspect that he’s being controlled by some being in another dimension, are unexpectedly spine-tingling.

Black Mirror’s sixth season is on Netflix now; and while none of its episodes is interactive, the first in the series, called Joan is Awful, contains a fun nod to Bandersnatch. In an episode largely about a thinly-veiled version of Netflix – a company called Streamberry – we catch a glimpse of a series of shows, all lined up on a distinctly Netflix-like menu. One of those shows? Something called Finding Ritman – a reference to the game designer Colin Ritman, played by Will Poulter in Bandersnatch.

Credit: Netflix.

With the tech industry facing its own credit crunch in recent years, and streaming firms cutting back on costs and trying to claw in profits by other means – like Netflix ending password sharing – it looks less likely than ever that we’ll see anything quite as expansive as Bandersnatch appearing any time soon. Netflix’s more recent interactive specials have largely been based around children’s content (Boss Baby: Get That Baby!) and smaller-scale quizzes like Trivia Quest and Triviaverse.

Brooker’s most recent interactive experience for Netflix appeared in 2022 – the playfully anarchic cartoon, Cat Burglar. Although beautifully animated, its quiz-based approach – where questions had to be answered within a strict time limit – felt less ambitious than Bandersnatch. Nor was Cat Burglar as long; each playthrough takes around 10 minutes, and there’s about 90 minutes of animation in total – far less than the five hours of footage in Bandersnatch.

Perhaps Brooker himself summed up the situation best in a 2022 interview with Comic Book Resources. “The main lesson I learned from Bandersnatch was,” he said, “‘Don’t do it.’”