Darkest Dungeon II, Humanity and After Us all dared to emerge in Tears of the Kingdom’s shadow last month. All offer a sense of hope in an uncertain world.

When we look back at May 2023, The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom will no doubt dominate the collective gaming memory. Nintendo’s latest big thing is at the top of the new release food chain this year, and cast a shadow over anything that dared to release within its orbit. Yet some games did dare, and among them were those that embodied that refusal to stand aside for the giant action RPG. These titles ensured that, if there’s anything May 2023 should be remembered for other than Zelda, it’s defiant optimism, and hope for us all.

Indeed, Darkest Dungeon II, Humanity and After Us are all in different ways about hope, with the first two of the trio in particular also among the best-in-class in their respective genres (After Us is pretty good, too). The similarities may not be immediately apparent, but played back to back they flesh out a notion of optimism that goes beyond games and into the world around us. They symbolise a crisis in our societies, civilisation, and species, while emphasising our potential to find a way out.

It takes a while to get to the uplifting parts, though, as all three games drag us into some pretty dark depths, even the brightly lit Humanity with its chummy doggy protagonist. But that’s precisely the means by which they make hope feel authentic, in contrast to the escapist confection of utopian ‘cosy’ games. If hope is anything, surely it requires friction and the possibility that things could also go horribly wrong.

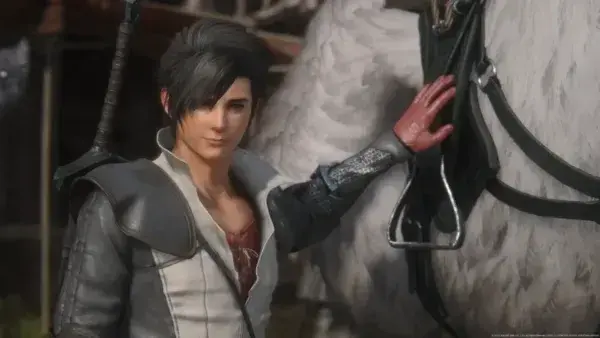

Credit: Red Hook Studios.

When you start Darkest Dungeon II, for example, you enter a land of misery and torment, overrun by disease, death cults and Eldritch horrors. But the game quickly bolsters your determination to see this world change with the introduction of its flame of hope – a torch that burns atop the horse-drawn carriage you ride, symbolising a fading glimmer of optimism. When you die, as is highly likely, this flame continues in the form of candles, a currency you use between runs to unlock permanent upgrades.

Darkest Dungeon II will routinely subject you to crushing defeat, even sometimes when you feel a run is going well, as a particularly prickly encounter tramples on your dreams in short order. Yet thanks to those candles, along with the near-endless combinations of characters you can try out, all the skills you can choose between, and the gradual boosts you accrue, despair loops back round to hope again.

This is how hope becomes meaningful. Historically, people have fought for better social conditions without knowing in advance that they would succeed. Sometimes there’s no choice but to try, and besides, even failure keeps the flame alight, offering hope to the next generation. In Darkest Dungeon II, there’s a sense of achievement in at least failing better – beating the lair boss that destroyed your last expedition based on their experiences, even if that party itself falls soon after.

Hope in Darkest Dungeon II also relies heavily on togetherness, with its affinity system determining how the characters in your party relate to each other. Each time you rest at an inn, high affinity may cause friendships to blossom, granting bonuses to some of your skills, while low affinity can cause envy and hatred, adding negative side effects to certain moves. In short, making something of hope is not only a matter of strategy, but unity, focused on a common goal.

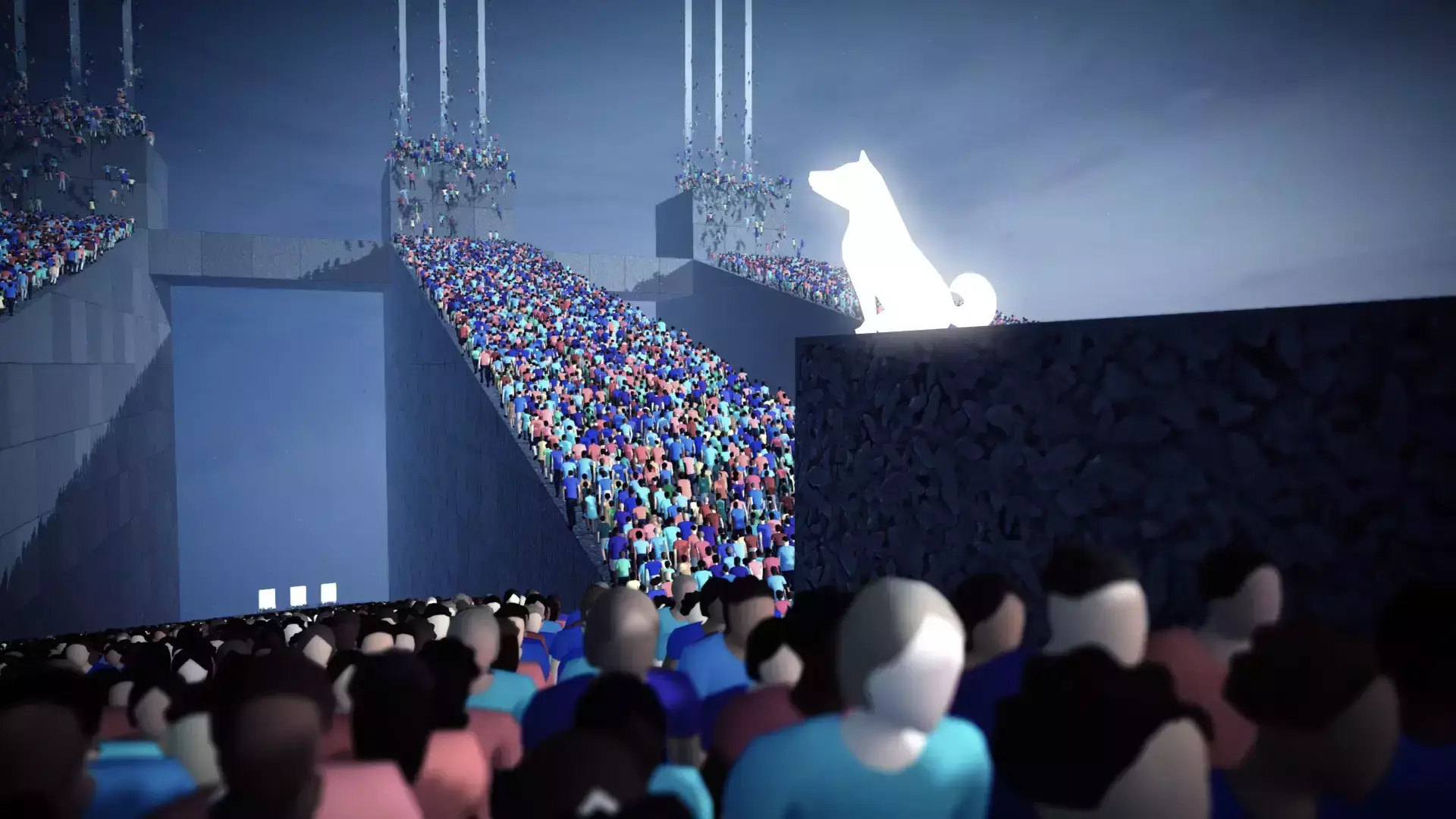

Credit: Enhance.

In Humanity, conversely, it’s not about collaborating so much as ordering people around, barking commands from your canine avatar to shift lines of shuffling humans towards a stage exit. This is the vehicle, however, for a journey through the gamut of our species’ existential issues, with puzzles based around themes of choice, competition, dependence and more.

Regardless of what aspect of humanity comes to the fore, though, it’s invariably accompanied by terrible, meaningless death. Success means martialling your humans into beautiful patterns like an engineer, but you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few (hundred) eggs. If streams of people are falling to their doom, it’s as likely to be an unfortunate by-product of progress as a sign that you’ve done something wrong.

Read more: Humanity review | People are lemmings

Then, once the game evolves towards its chapter on War, carnage becomes a matter of intent. Now you have to beat an opposing faction of ‘Others’ to reach your goals, and like a World War I general you send troops over the top to try and swamp your opponent with sheer numbers, irrespective of the cost. War is part of humanity, of course, and as soon as the ‘Others’ are introduced this outcome feels like a sadly inevitable escalation.

It would be easy for Humanity to settle on a cynical view of human nature here – resigned to our greed, selfishness and aggression. But while it’s obviously true that untold death and destruction lie in the wake of advancing civilisations, the game refuses to deny other, equally real, aspects of our existence. Civilisation ultimately reflects all our traits after all, pushing against one another. And in its level creator, Humanity finally places its hope in us, to remake our societies. We can either trust in fate, it suggests, or be an active part of producing our own future.

Credit: Piccolo/Private Division.

As for After Us, well, its themes are front and centre, as you explore an abstract future world in which human-made environmental decline has claimed life of all kinds. Playing as a fragile nymph-girl serving Gaia, the spirit of nature, you set out to find and release animal spirits to give the world a second chance. The journey takes you through colossal landfill sites and grimy factories, and under oceans clogged with sunken ships and trawler nets. You dodge buzzsaw blades and shots from hunting rifles in a barren forest, and clamber up a great beehive, whose inhabitants have turned into empty husks.

On a literal level, the hope here is fantastical – a post-human dream that the world might rejuvenate itself once we’ve gone. But at the same time, After Us isn’t about ‘us’ as a species but ‘us’ as the people alive now, and what will be left for those who arrive later. The narrative device here is that of the future anterior, imagining the present from the perspective of the future, which allows us to contemplate the path to ruin. Considering that future prompts us in turn to consider how to avoid it, with the hope that’s still possible.

Read more: After Us | Creating hope amongst ruins

All these games can achieve, of course, is inspire us to think that alternative, better ways of existing are still within our reach. The hope they offer is at best a catalyst, or an abstract potential as yet unrealised. It doesn’t inevitably lead to positive change, or provide a programme for getting there. Indeed, hope as a political force can even be counterproductive, promising something that isn’t delivered, depleting the reserves of hope a society holds.

As we see in these games, hope works best not when we place it in others, but when we take responsibility for keeping it alive. Perhaps in the present things feel quite hopeless – politically, economically, culturally, environmentally. As we feel largely powerless to affect the world, it’s easy to hope weakly that eventually the systems themselves fail, enabling people to start afresh. Yet Darkest Dungeon II, Humanity and After Us imply something stronger. If you haven’t already, put down Zelda and give them a chance.

Darkest Dungeon II, Humanity and After Us are all available now.