The castle in Ico delivers a powerful atmosphere, demonstrating that games are stronger when elements are removed, not added…

Released for the PlayStation 2 in 2001, then re-released on PlayStation 3 in 2011, it’s fair to say that Ico (pronounced “ee-ko”, by the way) was not a big sales success. But despite that, over time it’s become something of a cult classic and is credited with inspiring the developers of games including Uncharted 3, RiME, FEZ, Halo 4, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, and The Last of Us. Film director Guillermo del Toro even called Ico a masterpiece.

But what makes this game so special? At first glance, it’s a simple 3D platformer, with you controlling the young boy Ico as he pulls levers and thwacks shadow monsters in an attempt to free himself and the enigmatic Yorda from a decaying castle. But beyond its accessible gameplay and easily graspable goal, perhaps the biggest key to Ico’s success is its incredible atmosphere, and it gains most of that from its environment: the castle in the mist.

STORY THROUGH PLACE

So important is the environment, that while Ico and Yorda are obviously the centre of attention, you could argue that the game’s third character isn’t the evil queen – you’re rescuing a princess, of course there’s an evil queen – it’s the castle itself. The huge structure is a maze of soaring, crumbling towers and sun-dappled courtyards, all connected to the distant mainland by an impossible bridge.

Note how far away the camera gets from Ico, helping you plan routes and solve puzzles but also reinforcing the massive scale of the castle.

Most of the castle’s dusty chambers are empty, with few signs of habitation beyond the occasional chandelier or torn curtain. But while it’s easy to put your developer hat on and rationalise the lack of furniture as a limitation of 20-year-old hardware, the sun-baked textures give everything the feel of desiccated age, making it plausible that the flimsy trappings have rotted away, leaving just stone and metal.

Importantly, there are enough details – a graveyard, a rail cart, prison cells – to give a sense that people must have lived here once, but with the game never neatly laying out its plot, it’s left to you to ask questions. Where did the inhabitants of the huge castle go, and why did they leave? Was this place built for the queen who lurks at its heart, or did she arrive later? Even why Ico has horns is left ambiguous (though see the Castle in the Mist sidebar for more about the game’s novelisation).

By now, I’ve described pretty much all of the game’s elements; a few characters, some straightforward 3D platforming and combat, and a desolate environment. But rather than a weakness, this lack of ‘stuff’ is one of the game’s core pillars, and comes from the development approach that Fumito Ueda and the rest of the team took of stripping away as much of the game as possible.

DESIGN BY SUBTRACTION

Design by subtraction means questioning whether each element of your game is important enough that it needs to remain in the game, and cutting it away if not. For example, Ico was originally going to feature human enemies, flying robots, and the castle under siege, but all this was removed to bring the game back to its fairytale core of a boy and a girl trapped in a dangerous environment.

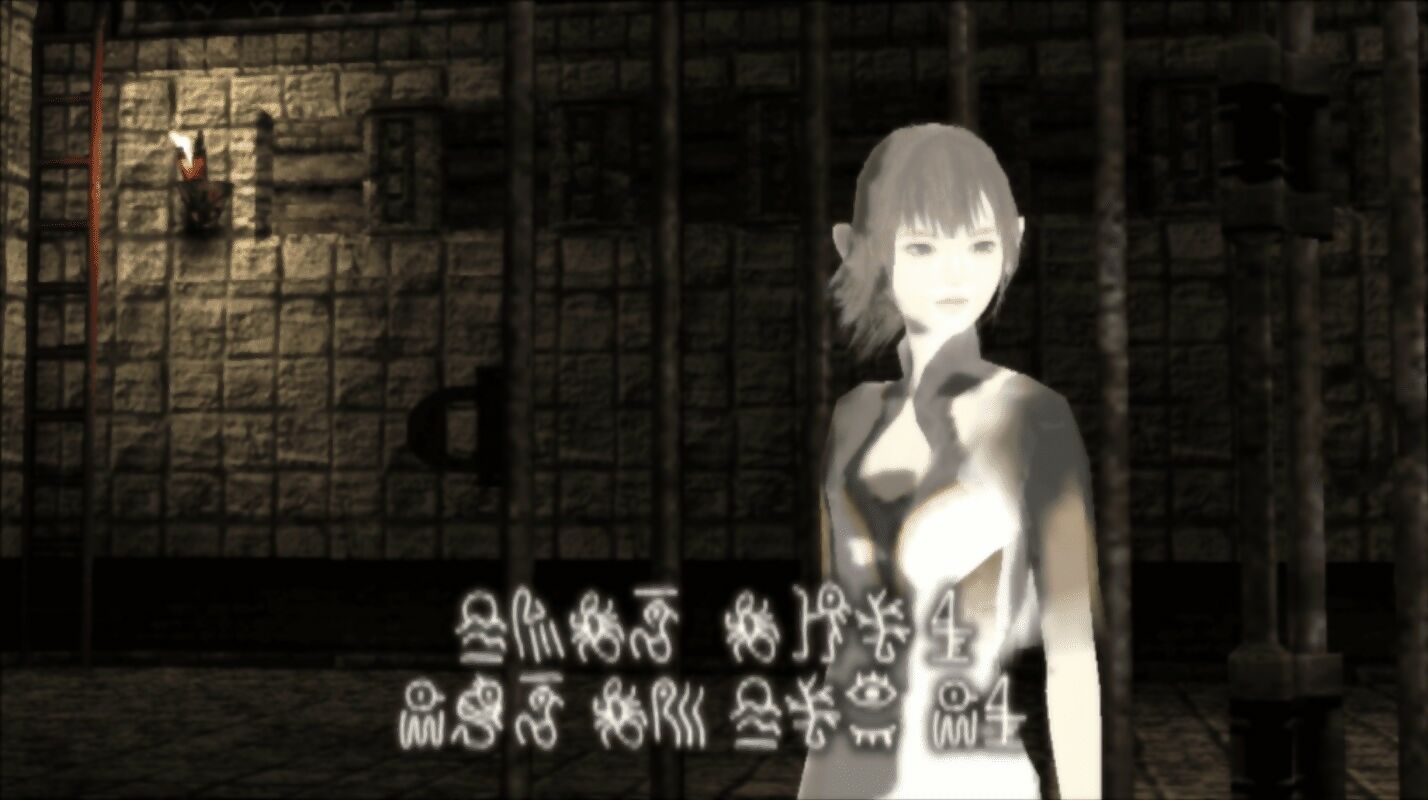

Keeping Yorda’s subtitles unreadable makes her seem alien and mysterious, but also avoids the ‘why doesn’t she just tell you what’s going on?’ problem.

While you can use design by subtraction to remove features, enemies, and plot points to help release your game sooner or because they’re causing technical problems, the main reason you remove them is to enhance your vision for the game. To this end, Ico features no HUD, no health, no map, no inventory, and very little explicit storytelling. The goal of escaping the castle is clear but everything else is left for you to figure out, to the extent that fans argue about how much of the game actually takes place in ‘reality’ and what’s in your character’s head.

With everything that might get in the way stripped out, you can’t help but focus on what remains – the castle. And that castle isn’t just a backdrop to the action, it’s the embodiment of the evil queen (at one point in the game’s novelisation, the queen says, “I am everywhere… The Castle in the Mist is me, and I am the castle”). By linking the two, even without a detailed back story or objective markers, your goal could not be clearer: you need to escape.

DETAIL IS IMPORTANT

While it’s obvious that some elements of the castle were designed around a puzzle first, it remains a coherent, ‘real’ place. The battlements give a distant view of the mainland, there are drainage tunnels, a windmill, grand chambers and fallen bridges, and at the centre of it all, there is of course a throne room. The castle’s sense of solidity is enhanced by the game refusing to cheat in its layout, with vantage points often showing locations you’ve already visited or will do in the future. Super-fan ‘Nomad Colossus’ even stitched together a map of the entire castle from hundreds of screenshots, showing how it twists back on itself and avoids arbitrarily teleporting you from location to location. The environment is too sprawling and complex to hold in your head while playing, but the team’s effort in laying it out like a real place pays off by allowing you to see that you’re making progress as you glimpse where you’ve been and get a peek at where you’re going.

The game frequently shows you where you’ve been and hints at future areas, making the castle feel like a real place, not an abstract video game.

Another side effect of this ‘everything in the game is there for a reason’ approach is that it invites you to wonder about the details of the environment, because the fact that they exist means they must be important. For example, the long staircase up to Yorda’s cage is ringed with spikes, but they point inwards towards her, not out towards you. Or that the castle is made from what must be millions of bricks, not carved from the rock it sits on, making you wonder who built it and how long it took. Or that a sword’s blade is trapped between the huge doors of one of the arenas, leaving you to wonder who it belonged to and how it became wedged there.

PRACTICAL EXAMPLES

As an example of how you could apply Ico’s ‘less is more’ approach to your environments, you could ask whether your game really needs a HUD arrow or objective marker guiding players to their destination. While markers are clear and convenient, perhaps players would become more immersed in your game if they have to remember that their destination is damp and swampy, look around, and realise that a particular corridor leading downwards is similarly slimy. Of course, this approach will slow your game down, as players need to spot and figure out these clues, meaning you wouldn’t do this in an action game (though if you want a fast-paced game, you’re probably better off not asking players to pause and choose a direction at all).

The game reinforces the bond between Ico and Yorda in small ways, such as them needing to sit down together to save the game.

Or perhaps you could leave sections of your game world empty of puzzles and threats in the same way that Ico often does (an approach also used in 1997’s GoldenEye 007), suggesting that you’re exploring a real place that was here before you arrived, not an artificial environment set up around gameplay.

Finally, consider how Ico removes most of your control over its camera, allowing the developers to have it looking down at you from a distance, giving the game a voyeuristic, ‘being watched by CCTV’ feel. It also adds stress by making it difficult to see where Yorda is when she wanders away from you.

The game reinforces this tension early on by having shadow monsters close in on Yorda when she’s left alone too long, meaning for the rest of the game you’re nervous about getting too far away from her.

PARING BACK

It might seem counter-intuitive that removing elements can enhance your game, but when you do so, it means that the elements you have included gain ‘weight’ and become more important. You see this in the atmosphere built up by Journey’s ruins, Flashback’s deserted streets, and The Stanley Parable’s silent offices, but, in my opinion, Ico is the pinnacle of this approach. The game strips away any explanation of why all this is happening to you, how this world works, and even how the game ends, leaving you with questions and theories that linger long after you’re done playing.

In the queen’s rare appearances, she towers over the children, reminding you just how small and powerless they are in this huge place.

That said, it is worth pointing out that in interviews, Ueda wondered whether they’d gone too far in stripping Ico back, perhaps leading to its poor sales by confusing players looking at screenshots who were left wondering what sort of game this was. It’s notable that Ico’s follow-up, Shadow of the Colossus, included more traditional video game elements, such as a HUD showing your stamina and glowing beacons to help you navigate. Videos, genre tags, and text descriptions all help, but people still use screenshots to gauge if a game might be for them, so you need to ensure you leave enough clues about how your game might play.

All this talk about design by subtraction sounds very dry and (ironically) reductive, but the point isn’t simply to remove as much of your game as you possibly can. Rather, it’s to question each element and ask if it’s helping to tell your game’s story, enhance your theme, or give your game a sense of place.

As a final example of removing expected elements, the vast majority of Ico is played without music, leaving just Ico’s footsteps and breathing, the crackling of torches, bird calls, and the ever-present wind.

Again, the game avoids taking a more obvious cinematic approach in favour of rooting you in the sounds of the environment you’re exploring. Still, there are occasional pieces of music, including the end credits track, You Were There, a title that I think perfectly sums up the genius of Ico and its castle. By removing as many ‘video game’ elements as possible, the developers did everything they could to immerse you in the lonely and mysterious castle in the mist. You really were there.

1 Comment

Great analysis. I was thinking about this recently while revisiting Ico while I was playing Uncharted 4 (which is pretty much the opposite – more is less – while extremely impressive and similar to Ico in some respects).