The composers of Frog Detective, Psychonauts, Fallout and Starfield explain how they make unforgettable music for video games.

If, like me, you’ve bellowed out an operatic impression of the Halo theme in the shower, or found yourself humming the DK Rap long after hearing it pop up in the Super Mario Bros. Movie, you’ll know how pervasive and catchy video game music can be. Hell, even Drake couldn’t resist sampling Donkey Kong Country 2. Nowadays, a YouTube search for your favourite theme will uncover all manner of remixes. From the bit-crushed to the orchestral, the lo-fi to the nightcore, video game soundtracks are so culturally significant (and catchy) that they’re no longer contained works, existing solely within the confines of the software. Instead, they have the capacity to branch out beyond the credits and influence the world around them.

This, of course, all comes down to the work of talented artists, who craft tracks to capture the inimitable spirit of a virtual world. To get a better understanding of how this process works, I contacted a range of industry composers to get a glimpse behind the curtain and unravel some of the musical magic hidden in our favourite games. Where do they even begin?

“I really like to know what the developers hope their players will feel while playing,” said Australian composer Dan Golding, whose jazz-infused rhythms can be heard throughout iconic indies like the Frog Detective series and Untitled Goose Game. “Before I think of genre or visual design or anything like that, I’m curious to hear what we’re thinking in terms of audience. Not who they are or demographics, but what their time with the game should be like emotionally. I put myself in the shoes of the audience as best as I can, and only then really think about what kind of music will help me get there.”

Golding’s work on the Frog Detective series is an excellent example of how composers can embellish the atmosphere of a game and speak to its intended audience in interesting ways. Golding’s committed noir soundtrack consistently amplifies the game’s roguish humour. “Originally, [Frog Detective designer] Grace Bruxner approached me with the thought that the music might sound a little like the BBC Hercule Poirot music by Christopher Gunning, and the idea of shifting it a little so that it fit the musical world of a frog really tickled me,” Golding said.

Thanks to the breaks in development between the trilogy, Golding could come to each new puzzle with fresh ears, colouring the world with contextual notes depending on the setting, which ranges from fantasy forests to the Wild West. “Because the games are inherently funny, I think I’ve been able to play with music genre a little bit more directly than I otherwise would,” Golding explained. “I strongly believe that the music shouldn’t be in on the joke in the Frog Detective games. Things are funnier when the music takes events as seriously as the characters do.”

Like the trio of cases in the Frog Detective series, each mental world that Raz explores in Double Fine’s Psychonauts is an explosion of visual variety. Herein lies another challenge for video game composers: with the wide-ranging visual references offered by video games, how do you craft a compositional identity? “It was truly a challenge, not so much in coming up with the different styles, but in weaving them all together,” said Peter McConnell, composer of Psychonauts, Monkey Island and Grim Fandango. “I’ve lived in a lot of places in my life, from Switzerland to California, and have had even more musical influences than places I’ve lived. So each character and place connects to me directly in some musical way. The trick is binding them together, and that I did through the use of repeated themes and leitmotifs.”

Leitmotifs are recurring musical fragments and themes, often layered throughout video game soundtracks to point towards specific characters or ideas.

“We game composers have inherited the use of leitmotifs from classic 20th-century film scoring, which in turn drew heavily from 19th-century opera; in particular, from composers like Carl Maria Von Weber and Richard Wagner,” McConnell said. “I always keep a score of Wagner’s Die Walküre where I can see it. Much as Die Walküre has a leitmotif for the hero’s enchanted sword, the Star Wars scores have a leitmotif for the Force.

“On a more humble level, there’s a leitmotif for the Psychonauts as a team of heroes which is present almost everywhere in the Psychonauts 2 score. It’s stated explicitly in the main theme and more subtly in the clarinet melodies associated with the main character Raz, a good example being the opening lines you hear in the Questionable Area. You also hear hints of it in the “Meat Circus” music and the Aquato Family acrobatic music. All in all, there are few pieces in the game that don’t have a leitmotif in them somewhere.”

Leitmotifs can offer tasteful reminders of who you’re interacting with as well as the key thematic elements of the plot as you move through a game’s world. This helps ground you in the wider narrative context of the adventure, but the unique capacity for non-linearity in video games means that the composer isn’t always in control of the musical experience. Oftentimes, you may find yourself wandering in the same location, scouting out collectables and side quests, or simply enjoying the vibes.

One such vibe-heavy hub is Whispering Rock Psychic Summer Camp from Psychonauts, whose loot-covered landmarks can keep you in one place for extended periods of time. From a musical perspective, maintaining a player’s interest in these areas can require some lateral thinking from composers.

“There are many techniques for maintaining musical interest through many repetitions,” said McConnell. “In (Whispering Rock), the chord progression is a little off-centre, which I think makes it hold up under repeated listening, even if the pattern itself is short. Also, I try to construct the form of the piece so that the loop point – the point where the music actually repeats – is hard to identify. Finally, the piece consists of layers which are varied in real-time response to gameplay, which, as I recall in this case, depends on which room the player is in.”

Another composer who understands the careful balance that comes with writing for open-world areas is Inon Zur, the maestro behind the experimental retrofuturist soundscape of the modern Fallout series, which blends comic levity with dystopian tension. “With Fallout, I apply a non-traditional element in terms of instrument selection, and this supports the concept of the world,” Zur said. “In many cases, I will have non-traditional instruments, even random objects and tools such as chairs or vases, whereby I’m playing them. Also, I‘m taking legitimate instruments like piano and guitar and playing them in a very non-traditional manner.”

Yet even with such a compelling, clearly inspirational backdrop to play with, a key part of Zur’s process is working to complement the player’s experience, even when they’re grinding out XP in a radiated cul-de-sac. “One approach is to create a piece that will be repetitive enough that players will become familiar with it, but on the other hand, I need to provide enough variation so it does not become tiresome for the player,” Zur explained.

The theme that plays throughout the sterile halls of The Institute in Fallout 4 is typically dynamic – calm on the surface but subtly unnerving, which cleverly embodies the space and its place in the game’s narrative. After exploring its nooks and crannies, the theme has stuck with me, so much so that I now use it as a study aid – and with 44 thousand views on YouTube, I’m clearly not alone.

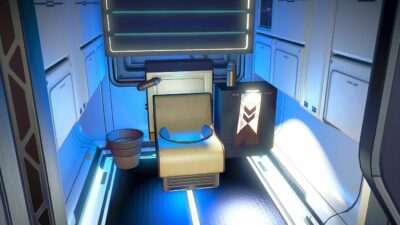

In lieu of a new Fallout game on the horizon, Zur has had his hands full developing the musical world of Starfield, Bethesda’s next big RPG. No mean feat, given that it has been reported to have over 1,000 planets to explore. “When I was first presented with the notion of Starfield seven years ago, it was just a concept, just an idea,” Zur said. “So the more open-ended music was written before I even saw the game. Starfield is a huge universe of exploration, with all the mystery and revelations of outer space. It’s an epic game of hope and wonder, asking the big philosophical questions: where did we come from, and where are we going? Once you embark on this journey, it’s immensely captivating and deeply emotional, and the music conveys this shared adventure for humanity.”

When it comes to writing music for video games, the dynamic nature of the medium ensures that there’s no shortage of fascinating considerations, and keeping all of those peculiar plates spinning over the course of an entire adventure is a herculean undertaking. Yet, by leveraging clever techniques like leitmotifs, understanding the relationship between player and soundtrack and the indulgence of creative inspirations, composers can summon soundscapes that are so compelling they tend to live on with the players who experience them.

Even with all the considerations in the world, though, it’s clear that video game composers are always at the unpredictable mercy of players, who never cease to make their jobs delightfully interesting. “I watched Limmy play some of Frog Detective 3 and was basically horrified to hear little cues that I’d written on the assumption that 99% of players would be through the scene in 30 seconds,” said Golding. “And there he was, hanging out in the same scene for 30 minutes. Horrifying.”

Read more: Richard Jacques | Exploring the composer’s sci-fi symphonies