Video game graphics owe a huge debt to Nolan Bushnell and a chap named Danny Hillis…

The word sprite comes from the Old French word ‘esprit’, meaning ‘spirit’ – derived from the Latin term ‘spiritus’. In folklore, sprites were small beings that were lively, playful, and magical. These days, certainly to the likes of you and I, they’re two-dimensional images that play a role within a larger environment. From Pac-Man to Mario to Sonic, it’s the perfect word to describe them.

The definition of what makes something a sprite, and the way in which they were created, has changed over the years, but sprites are so ubiquitous in gaming that it’s almost difficult to believe they had to be invented. I mean, it’s almost a chicken-and-egg thing. Over time, the classic pixel sprite became an art form in itself, a sort of impressionistic rendition born out of necessity.

When polygons sunk their claws into gaming during the nineties, the sprite quickly fell out of fashion, in the same way as deely boppers, Hypercolor sweatshirts, and shoulder pads. Even at the time, I always felt it was unjust how sprites got scoffed at by the gaming fashionistas, as they became increasingly dazzled by 3D images. Those early, flat polygons never seemed as characterful as what could be achieved by a good pixel artist, working within the limitations of a system’s hardware.

Now, of course, it’s all come full circle. The rise of indie gaming over the past decade or so has seen sprites and pixels re-emerge, their artistic potential being used as a selling point, rather than a best solution to the age-old limits of processing power. Shovel Knight, Owlboy, Downwell, Dead Cells, and the like, embraced that retro aesthetic and re-established it in a modern way. Modern sprites are an artistic choice, rather than a default requirement.

Cheese

The sprite, as with so much else, was invented by legendary Atari founder Nolan Bushnell, also the Chuck E. Cheese man. His Computer Space, the first arcade video game, was based on 1962’s Spacewar!, which ran on a powerful mainframe computer. The space rockets in that game moved around by refreshing the entire screen every single time anything happened.

That was untenable and inefficient for what was intended to be a commercial product – on-screen images would swallow up data enormously – so Bushnell reduced the processing demands by designing the ships in Computer Space to move independently from the background. Though the visuals of Computer Space looked very different from the way sprites would evolve, Bushnell’s innovation pointed the way forward for game development over the next two-and-a-bit decades.

Another gaming legend, Space Invaders creator Tomohiro Nishikado, pushed the form further forward with 1974’s imaginatively titled TV Basketball. A four-player variant of the even more imaginatively titled Basketball, released earlier the same year, it was effectively a variant of Pong. What set it apart is that the paddles were designed to resemble human players, and the goals looked like baskets. Though crude by today’s standards, at the time it was a revelation. Though strictly black and white, the opposing teams even had their own ‘colour’ scheme, making two of the players appear greyer than

the others by removing horizontal lines across their bodies.

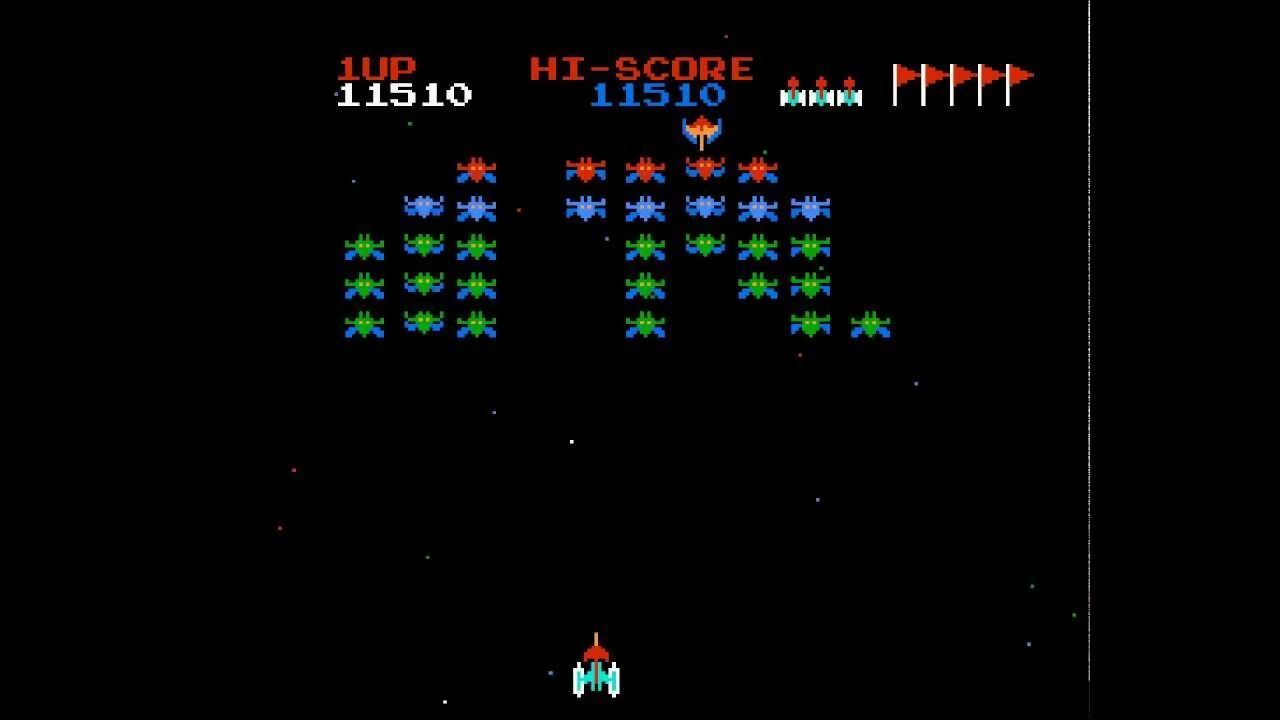

It would be a while yet before sprites could be animated, or depicted in full colour, however. Namco’s Galaxian arcade board – used in a number of games in the late 1970s and early 1980s – allowed for multicoloured sprites to be laid atop scrolling backgrounds. Sega was

but one company that licensed the technology, which could be seen in games such as Moon Cresta and Frogger.

Scramble

Konami’s Scramble – and indeed its spiritual successor, Super Cobra – added side-scrolling, while the long-forgotten Jump Bug, released by Sega, introduced parallax scrolling to the mix.

When games truly got a foothold in our homes, sprites were the only way to go. You may be forgiven for not remembering the 1292 Advanced Programmable Video System – a console released by Audiosonic back in 1978 – but it used the Signetics 2636N, a processor capable of throwing four single colour sprites (or ‘objects’, as Signetics called them) onto the screen at any one time. It was also capable of displaying a single sprite with eight colours. The 59 games released over the course of its relatively short life were mostly clones of popular arcade hits or sports simulations, but they weren’t dissimilar to the sort of thing you could find on the Atari 2600. Had Audiosonic been a bit quicker about it, the story of gaming might’ve played out very differently.

Of course, as history records, the Atari 2600 got there first, a full two years before Audiosonic, and had already trumped the 1292 and the Signetics processor, with five on-screen ‘moveable objects’, or ‘player missile graphics’, at a time. There were limitations in terms of how much could be on-screen at one time, but what programmers could achieve was remarkable, especially given the 2600 had no dedicated graphics memory. Its graphics were drawn one line at a time, with the CPU essentially redrawing the screen whenever something moved or fired. That almost iconic flickering in the 2600 version of Pac-Man? That was basically a cry for help.

While Atari used a number of different terms for these visuals – player/missile graphics, objects, and so on – others called them stamps (such as in Ms. Pac-Man), while Commodore favoured movable object blocks, or MOBs.

The first person to use the term ‘sprite’ was computing pioneer Danny Hillis, while working for Texas Instruments in the late 1970s. Hillis designed a chip for the TI-99/4, which allowed multiple characters to move on screen at the same time. He referred to these characters as sprites, due to the way in which they floated independently over the background. You may not remember the TI-99/4, although it was for a brief time the best-selling computer in America, but you will no doubt know of the Nintendo Entertainment System, which also used Hillis’s chip. Without it, we’d have had no Mario, no Donkey Kong, no Ice Climbers, no Punch-Out!!, or that dog in Duck Hunt.

Sprites made gaming, but more than that, they gave us character, and characters. That’s the real legacy of Nolan Bushnell’s invention