Writing CityCraft has been an incredibly rewarding experience. I had to carefully think about, and often re-evaluate, the ways imaginary cities need to be designed. I had to distil almost instinctive choices and methods into articles that made sense to readers, and thus get to examine my own thought processes. I learned a lot, had great fun, and hope this series has been equally enlightening for Wireframe’s readers.

In this final entry, I’d like to thank you all for your support, kind emails, and questions. Additionally, I want to thank the Wireframe team for putting up with me, the talented people who masterfully edited my words, and our wonderful editor, Ryan Lambie, for the opportunity to share and discuss game cities with such a brilliant audience. Four years and 70,000 words later, however, and it’s time to bring this journey to an end. We’ve taken in fundamentals, case studies, tips and rules, and even a few interviews and retrospectives.

Though I do hope to occasionally return to the pages of Wireframe with a feature or two, this article will be the end of my public writing on game cities for a while. So, what better way to close things off than with a selection of the real and imaginary places that have inspired my work?

Real-life cities

Studying real places is a must when designing virtual cities. From the ways buildings intermix and sidewalks curve, to architectural variations on dominant styles and transportation, physical city spaces can provide us with useful observations. Systems, patterns, rhythms, and solutions are all waiting to be noticed as every city offers layer on layer of useful information.

A glimpse of the beautiful canals of Venice, as rendered in Assassin’s Creed 2

My go-to city has always been Paris. Besides being a place I love, it’s a city I studied in detail, and is second only to my native Athens when it comes to familiarity. Its richly documented history encapsulates the often violent and aesthetically fascinating evolutions of urban space and society. On top of beautiful Montmartre lies a hated cathedral built to remind workers of their slaughter; medieval streets and architecture were documented and then destroyed to pave the way for capitalist innovations like the boulevards, with their maximised shopfronts. Every corner has a little story to tell about the city’s three revolutions, ancient past, and ambitious future. Cafés, bars, antique bookshops, working-class suburbs, downtown districts, exorbitantly priced restaurants, and indie artists coexist in a menagerie of medieval, baroque, modernist, and post-modernist buildings.

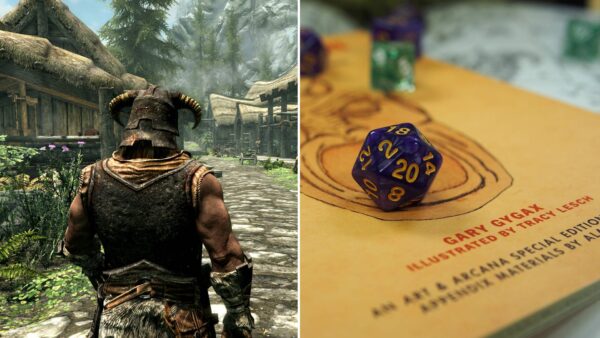

Venice, on the other hand, is a more unified and simpler agglomeration. It’s also the most beautiful city in the world. This early islandic democracy is a densely packed museum of exquisite architecture, and one of the rare places where Byzantine styles have survived. Murano was the glass-makers’ island, Burano specialised in lace, and the Ghetto was where the Jewish population was restricted. Its canals, criss-crossed by bridges, not only gave Venice much of its character, but also led to the birth of a new form of transportation: the gondola.

The Statue of Liberty, New York, New York, United States

Then there’s New York. I was in awe of Manhattan the first time I visited it – and I still am. The skyscrapers, Central Park, the brownstone and brick buildings, and the sheer vibrancy and cultural weight of the city are inescapable. Via countless movies, TV series, books, and games, images such as steam rising from the roads, ill-kept subways, vast crowds, or elevated trains are indelible, while the Statue of Liberty is one of the most recognisable urban landmarks in the world.

Virtual cities

Video game cities allow us to appreciate how talented developers have abstracted the urban fabric and condensed its physiognomy. Exploring them lets us see how systems interlock, how geography is implied, how navigation is supported, or how lines of sight are taken into account. While enjoying them, we can note the problems their creators solved in order to support gameplay and create a sense of place.

The amount of detail and interactive hotspots in Gabriel Knight’s location helped flesh out its world, and hinted at a more complex setting

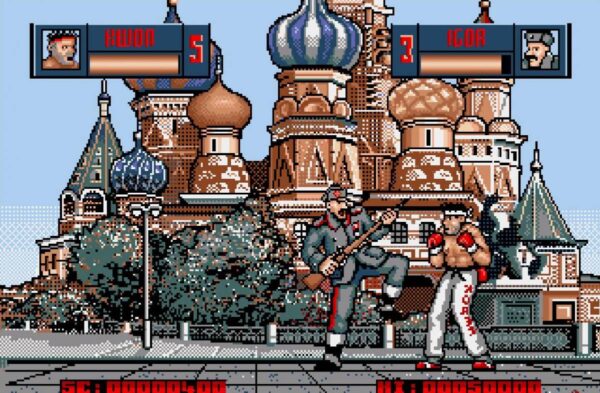

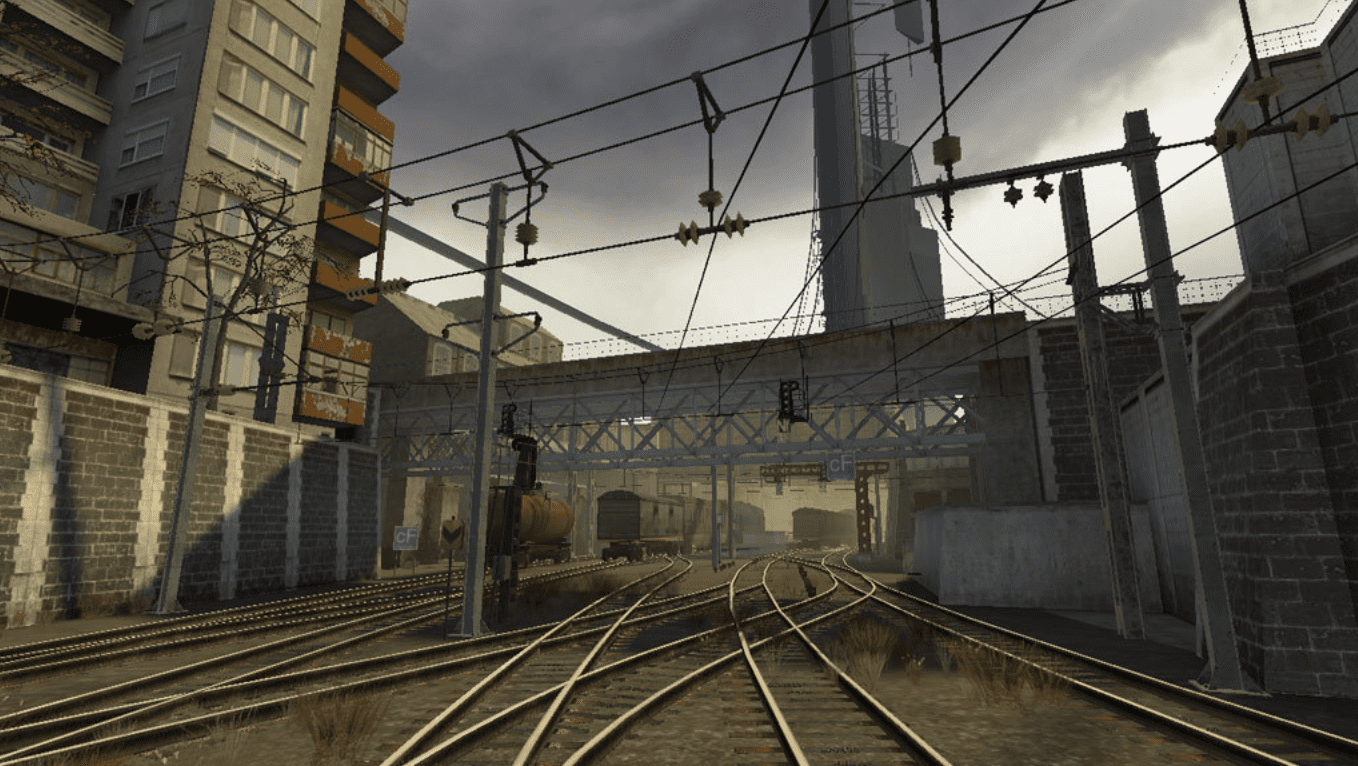

Half-Life 2’s City 17 remains one of the finest and most economically designed virtual cities. It’s a futuristic metropolis built using a minimal number of assets, arranged along planned routes that imply much and show little. City 17 instantly conjures a dystopian atmosphere with its surveillance, propaganda, and cops in riot gear. The city urged players to fix its problems, and, with the Citadel dominating the landscape, provided them with both a goal and a symbol of its oppression.

Beautifully recreated from 2D pixel art, the original Gabriel Knight’s New Orleans consisted of a handful of locations, but despite essentially being a collection of interactive backgrounds, the city felt cohesive, expansive, and impressively real. The density of detail in each location established a wider urban world, while its maps helped players build a larger space in their imaginations.

Gordon Freeman’s train journey into City 17 helped immerse players in Half-Life 2’s dystopia

What’s more, the image and atmosphere of New Orleans was masterfully distilled and represented as a place of voodoo, jazz, blues, Spanish moss, and intricate balcony railings.

Finally, The Witcher 3’s Novigrad is arguably one of the largest and most thoroughly fleshed-out fantasy cities in gaming. Supported by extensive historical research, Witcher lore, and well-picked inspirations ranging from the towers of San Gimignano to the docks of Gdańsk, Novigrad is both memorable and grounded in reality. Every district has an emphatic class and functional character, crowds are lively and purposeful, and the city is wisely treated as a continuous work in progress.